Everything For The Detectorist - Reference & Timelines

Powered By Sispro1

More Indepth notes on Metals

Source: Bibliography

Source: Bibliography

[1-17]

United Kingdom - The Roman Empire The First to Invade Britain

The British Library is also a good source to fill in the gaps of history

For an external link click onto the banner below to go to the British Library.

For an external link click onto the banner below to go to the British Library.

Click

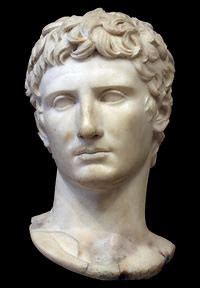

Augustus - Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus 63BC 19AD 14

NO!

NO!

Caligula - Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus 37 AD to 41AD

NO!

NO!

Emperors

Hadrian - Publius Aelius Hadrianus 78AD-138 AD

No!

No!

Roman Index Menu

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

5. Menu

Pages

Member NCMD

Double click to start editing the text

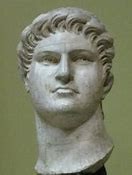

Gaius Julius Caesar

100BC- 44BC

100BC- 44BC

Caesar had been conquering Gaul since 58 BC and in 56 BC he took most of northwest Gaul after defeating the Veneti in the naval Battle of Morbihan.

Caesar's pretext for the invasion was that "in almost all the wars with the Gauls succours had been furnished to our enemy from that country" with fugitives from among the Gallic Belgae fleeing to Belgic settlements in Britain, and the Veneti of Armorica, who controlled seaborne trade to the island, calling in aid from their British allies to fight for them against Caesar in 56 BC.Strabo says that the Venetic rebellion in 56 BC had been intended to prevent Caesar from travelling to Britain and disrupting their commercial activity, suggesting that the possibility of a British expedition had already been considered by then.

It may also have been a cover for investigating Britain's mineral resources and economic potential: afterwards, Cicero refers to the disappointing discovery that there was no gold or silver in the island; and Suetonius reports that Caesar was said to have gone to Britain in search of pearls.

However, it may have been an excuse to gain stature in the eyes of the Roman people, due to Pompey and Crassus' consulship. On the one hand, they were Caesar's political allies, and Crassus's son had fought under him the year before. But they were also his rivals, and had formidable reputations (Pompey was a great general, and Crassus was fabulously wealthy). Since the consuls could easily sway and buy public opinion, Caesar needed to stay in the public eye. His solution was to cross two water bodies no Roman army had attempted before: the Rhine and the English Channel.

Planning and reconnaissance

Caesar summoned merchants who traded with the island, but they were unable or unwilling to give him any useful information about the inhabitants and their military tactics, or about harbours he could use, presumably not wanting to lose their monopoly on cross-channel trade. He sent a tribune, Gaius Volusenus, to scout the coast in a single warship. He probably examined the Kent coast between Hythe and Sandwich, but was unable to land, since he "did not dare leave his ship and entrust himself to the barbarians", and after five days returned to give Caesar what intelligence he had managed to gather.

By then, ambassadors from some of the British states, warned by merchants of the impending invasion, had arrived promising their submission. Caesar sent them back, along with his ally Commius, king of the Belgae Atrebates, to use their influence to win over as many other states as possible.

He gathered a fleet consisting of eighty transport ships, sufficient to carry two legions (Legio VII and Legio X), and an unknown number of warships under a quaestor, at an unnamed port in the territory of the Morini, almost certainly Portus Itius (Saint-Omer). Another eighteen transports of cavalry were to sail from a different port, probably Ambleteuse. These ships may have been triremes or biremes, or may have been adapted from Venetic designs Caesar had seen previously, or may even have been requisitioned from the Veneti and other coastal tribes.

In late summer 55 BC, even though it was late in the campaigning season, Caesar decided to embark for Britain.

Landing

Clearly in a hurry, Caesar himself left a garrison at the port and set out "at the third watch" (well after midnight) on 23 August with the legions so that they would arrive at dawn, leaving the cavalry to march to their ships, embark, and join him as soon as possible. In light of later events, leaving without the cavalry was either a tactical mistake or (along with the fact that the legions came over without baggage or heavy siege gear) confirms the invasion was not intended for complete conquest.

Caesar initially tried to land but when he came in sight of shore, the massed forces of the Britons gathered on the overlooking hills dissuaded him from landing there. After waiting there at anchor "until the ninth hour" (about 3pm) waiting for his supply ships from the second port to come up and meanwhile convening a council of war, he ordered the fleet to sail north-east along the coast to an open beach probably at Ebbsfleet.

The Britons had kept pace and fielded an impressive force, including cavalry and chariots, and the legions were hesitant to go ashore. To make matters worse, the loaded Roman ships were too low in the water to go close inshore and the troops had to disembark in deep water, all the while attacked by the enemy from the shallows. Eventually, the legion's standard bearer jumped into the sea and waded to shore. To have the legion's standard fall in combat was the greatest humiliation, and the men disembarked to protect the standard bearer. After some delay, a battle line was finally formed, and the Britons withdrew. The cavalry auxiliaries were unable to make the crossing despite several attempts and so Caesar could not chase down the Britons.

Beach-head

Recent archaeology by the University of Leicester indicates that the likely landing beach was at Ebbsfleet in Pegwell Bay where artefacts and massive earthworks dating from this period have been exposed. If Caesar had as large a fleet with him as has been suggested, then it is possible that the beaching of ships would have been spread out over a number of miles stretching from Walmer towards Pegwell Bay.

The site at Ebbsfleet is a defensive enclosure today about 1 km from the sea due to siltation of the former Wantsum Channel but in ancient times was on peninsula projecting into the channel. The defensive ditch enclosed an area of over 20 ha on the shore.

Skirmishes

The Romans established a camp and received ambassadors and had Commius, who had been arrested as soon as he had arrived in Britain, returned to them. Caesar claims he was negotiating from a position of strength and that the British leaders, blaming their attacks on him on the common people, were in only four days awed into giving hostages, some immediately, some as soon as they could be brought from inland, and disbanding their army. However, after his cavalry had come within sight of the beachhead but then been scattered and turned back to Gaul by storms, and with food running short, Caesar was taken by surprise by high British tides and a storm. His beached warships filled with water, and his transports, riding at anchor, were driven against each other. Some ships were wrecked, and many others were rendered unseaworthy by the loss of rigging or other vital equipment, threatening the return journey.

Realising this and hoping to keep Caesar in Britain over the winter and thus starve him into submission, the Britons renewed the attack, ambushing one of the legions as it foraged near the Roman camp. The foraging party was relieved by the remainder of the Roman force and the Britons were again driven off, only to regroup after several days of storms with a larger force to attack the Roman camp. This attack was driven off fully, in a bloody rout, with improvised cavalry that Commius had gathered from pro-Roman Britons and a Roman scorched earth policy.

The campaigning season was now nearly over, and the legions were in no condition to winter on the coast of Kent. Caesar withdrew back across the Channel with as many of the ships as could be repaired with flotsam from the wrecked ships.

Conclusion

Caesar once again narrowly escaped disaster. Taking an understrength army with few provisions to a far-off land was a poor tactical decision, which easily could have led to Caesar's defeat, yet he survived. While he had achieved no significant gains in Britain, he had accomplished a monumental feat simply by landing there. It was a fabulous propaganda victory as well, which was chronicled in Caesar's ongoing Commentarii de Bello Gallico. The writings in the Commentarii fed Rome a steady update of Caesar's exploits (with his own personal spin on events). Caesar's goal of prestige and publicity succeeded enormously: upon his return to Rome, he was hailed as a hero and given an unprecedented 20-day thanksgiving.

Second invasion (54 BC)

Preparation

Caesar's approach in the winter of 55 54 BC towards the invasion in 54 BC was far more comprehensive and successful than his initial expedition. New ships had been built over the winter, using experience of Venetic shipbuilding technology being broader and lower for easier beaching, and Caesar now took 800 ships, five legions (instead of two) and 2,000 cavalry. He left the rest of his army in Gaul to keep order. Caesar took with him a good number of Gallic chiefs whom he considered untrustworthy so he could keep an eye on them.

This time he named Portus Itius as the departure point.

Crossing and landing

Titus Labienus was left at Portus Itius to oversee regular food transports from there to the British beachhead. The military ships were joined by a flotilla of trading ships captained by Romans and provincials from across the empire, and local Gauls, hoping to cash in on the trading opportunities. It seems more likely that the figure Caesar quotes for the fleet (800 ships) include these traders and the troop-transports, rather than the troop-transports alone.

The Roman fleet sailed from France in the evening so that the army could land in daylight. They hoped to use the wind to help cross the Channel but midnight the wind dropped and the channel tide carried them too far northeast and at sunrise they saw Britain in the distance on their left. They managed to row and use the reversing tide to arrive at the place identified as the best landing-place the previous year.

The Britons had gathered to oppose the landing but as Caesar states, intimidated by the size of the fleet, withdrew 'and concealed themselves on the high ground' perhaps to give them time to gather their forces. Caesar landed and immediately went to find the Britons army.

Kent campaign

Upon landing, Caesar left Quintus Atrius in charge of the beach-head with an equivalent of a legion to build and defend the base. He then made an immediate night march 12 mi (19 km) inland, where he encountered the British forces at a river crossing, probably somewhere on the River Stour. The Britons attacked but were repulsed, and attempted to regroup at a fortified place in the forests, possibly the hillfort at Bigbury Wood, Kent, but were again defeated and scattered. As it was late in the day and Caesar was unsure of the territory, he called off the pursuit and made camp.

However, the next morning, as he prepared to advance further, Caesar received word from Atrius that, once again, his ships at anchor had been dashed against each other in a storm and suffered considerable damage. About forty, he says, were lost. The Romans were unused to Atlantic and Channel tides and storms, but nevertheless, considering the damage he had sustained the previous year, this was poor planning on Caesar's part. However, Caesar may have exaggerated the number of ships wrecked to magnify his own achievement in rescuing the situation. He returned to the coast, recalling the legions that had gone ahead, and immediately set about repairing his fleet. His men worked day and night for approximately ten days, beaching and repairing the ships, and building a fortified camp around them. Word was sent to Labienus to send more ships.

Caesar was on the coast on 1 September, from where he wrote a letter to Cicero. News must have reached Caesar at this point of the death of his daughter Julia, as Cicero refrained from replying "on account of his mourning".

March inland

Caesar then returned to the Stour crossing and found the Britons had massed their forces there. Cassivellaunus, a warlord from north of the Thames, had previously been at war with most of the British tribes. He had recently overthrown the king of the powerful Trinovantes and forced his son, Mandubracius, into exile. But now, facing invasion, the Britons had appointed Cassivellaunus to lead their combined forces. After several indecisive skirmishes, during which a Roman tribune, Quintus Laberius Durus, was killed, the Britons attacked a foraging party of three legions under Gaius Trebonius, but were repulsed and routed by the pursuing Roman cavalry.

Cassivellaunus realised he could not defeat Caesar in a pitched battle. Disbanding the majority of his force and relying on the mobility of his 4,000 chariots and superior knowledge of the terrain, he used guerrilla tactics to slow the Roman advance. By the time Caesar reached the Thames, the one fordable place available to him had been fortified with sharpened stakes, both on the shore and under the water, and the far bank was defended. Second Century sources state that Caesar used a large war elephant, which was equipped with armour and carried archers and slingers in its tower, to put the defenders to flight. When this unknown creature entered the river, the Britons and their horses fled and the Roman army crossed over and entered Cassivellaunus' territory.This may be a confusion with Claudius's use of elephants during his conquest of Britain in AD 43.

The Trinovantes, whom Caesar describes as the most powerful tribe in the region, and who had recently suffered at Cassivellaunus' hands, sent ambassadors, promising him aid and provisions. Mandubracius, who had accompanied Caesar, was restored as their king, and the Trinovantes provided grain and hostages. Five further tribes, the Cenimagni, Segontiaci, Ancalites, Bibroci and Cassi, surrendered to Caesar, and revealed to him the location of Cassivellaunus' stronghold, possibly the hill fort at Wheathampstead, which he proceeded to put under siege.

Cassivellaunus sent word to his allies in Kent, Cingetorix, Carvilius, Taximagulus and Segovax, described as the "four kings of Cantium", to stage a diversionary attack on the Roman beach-head to draw Caesar off, but this attack failed, and Cassivellaunus sent ambassadors to negotiate a surrender. Caesar was eager to return to Gaul for the winter due to growing unrest there, and an agreement was mediated by Commius. Cassivellaunus gave hostages, agreed to an annual tribute, and undertook not to make war against Mandubracius or the Trinovantes. Caesar wrote to Cicero on 26 September, confirming the result of the campaign, with hostages but no booty taken, and that his army was about to return to Gaul.He then left, leaving not a single Roman soldier in Britain to enforce his settlement. Whether the tribute was ever paid is unknown.

Caesar extracted payment of grain, slaves, and an annual tribute to Rome. However, Britain was not particularly rich at the time; Marcus Cicero summed up Roman sentiment by saying, "It's also been established that there isn't a scrap of silver in the island and no hope of booty except for slaves and I don't suppose you're expecting them to know much about literature or music!" Regardless, this second trip to Britain was a true invasion, and Caesar achieved his goals. One interpretation is that he had beaten the Britons and extracted tribute; they were now effectively Roman subjects. Caesar was lenient towards the tribes as he needed to leave before the stormy season set in, which would make crossing the channel impossible.

However, another interpretation of the details is that Caesar had made a weakly enforced treaty with the Catuvellauni, suggesting that a decisive victory did not occur upon the Britons. Caesar achieving popularity with the Roman peoples, and Cassivellaunus' achievement of the maintained autonomy of the Britons. This is evidenced via the next identifiable king of the Trinovantes, known from numismatic evidence, was Addedomarus, who took power c. 20 15 BC, and moved the tribe's capital to Camulodunum. For a brief period c. 10 BC Tasciovanus of the Catuvellauni issued coins from Camulodunum, suggesting that he conquered the Trinobantes in direct violation of the treaty.

Aftermath

Commius later switched sides, fighting in Vercingetorix's rebellion. After a number of unsuccessful engagements with Caesar's forces, he cut his losses and fled to Britain. Sextus Julius Frontinus, in his Strategemata, describes how Commius and his followers, with Caesar in pursuit, boarded their ships. Although the tide was out and the ships still beached, Commius ordered the sails raised. Caesar, still some distance away, assumed the ships were afloat and called off the pursuit. John Creighton believes that this anecdote was a legend, and that Commius was sent to Britain as a friendly king as part of his truce with Mark Antony. Commius established a dynasty in the Hampshire area, known from coins of Gallo-Belgic type. Verica, the king whose exile prompted Claudius's conquest of AD 43, styled himself a son of Commius.

Discoveries about Britain

As well as noting elements of British warfare, particularly the use of chariots, which were unfamiliar to his Roman audience, Caesar also aimed to impress them by making further geographical, meteorological and ethnographic investigations of Britain. He probably gained these by enquiry and hearsay rather than direct experience, as he did not penetrate that far into the interior, and most historians would be wary of applying them beyond the tribes with whom he came into direct contact.

Geographical and meteorological

Caesar's first-hand discoveries were limited to east Kent and the Thames Valley, but he was able to provide a description of the island's geography and meteorology. Though his measurements are not wholly accurate, and may owe something to Pytheas, his general conclusions even now seem valid:

The climate is more temperate than in Gaul, the colds being less severe.

The island is triangular in its form, and one of its sides is opposite to Gaul. One angle of this side, which is in Kent, whither almost all ships from Gaul are directed, [looks] to the east; the lower looks to the south. This side extends about 500 miles. Another side lies toward Hispania and the west, on which part is Ireland, less, as is reckoned, than Britain, by one half: but the passage from it into Britain is of equal distance with that from Gaul. In the middle of this voyage, is an island, which is called Mona: many smaller islands besides are supposed to lie there, of which islands some have written that at the time of the winter solstice it is night there for thirty consecutive days. We, in our inquiries about that matter, ascertained nothing, except that, by accurate measurements with water, we perceived the nights to be shorter there than on the continent. The length of this side, as their account states, is 700 miles. The third side is toward the north, to which portion of the island no land is opposite; but an angle of that side looks principally toward Germany. This side is considered to be 800 miles in length. Thus the whole island is about 2,000 miles in circumference.

No information about harbours or other landing-places was available to the Romans before Caesar's expeditions, so Caesar was able to make discoveries of benefit to Roman military and trading interests. Volusenus's reconnaissance voyage before the first expedition apparently identified the natural harbour at Dubris (Dover), although Caesar was prevented from landing there and forced to land on an open beach, as he did again the following year, perhaps because Dover was too small for his much larger forces. The great natural harbours further up the coast at Rutupiae (Richborough), which were used by Claudius for his invasion 100 years later, were not used on either occasion. Caesar may have been unaware of them, may have chosen not to use them, or they may not have existed in a form suitable for sheltering and landing such a large force at that time. Present knowledge of the period geomorphology of the Wantsum Channel that created that haven is limited.

By Claudius's time Roman knowledge of the island would have been considerably increased by a century of trade and diplomacy, and four abortive invasion attempts. However, it is likely that the intelligence gathered in 55 and 54 BC would have been retained in the now-lost state records in Rome, and been used by Claudius in the planning of his landings.

Ethnography

The Britons are defined as typical barbarians, with polygamy and other exotic social habits, similar in many ways to the Gauls, yet as brave adversaries whose crushing can bring glory to a Roman:

The interior portion of Britain is inhabited by those of whom they say that it is handed down by tradition that they were born in the island itself: the maritime portion by those who had passed over from the country of the Belgae for the purpose of plunder and making war; almost all of whom are called by the names of those states from which being sprung they went thither, and having waged war, continued there and began to cultivate the lands. The number of the people is countless, and their buildings exceedingly numerous, for the most part very like those of the Gauls... They do not regard it lawful to eat the hare, and the cock, and the goose; they, however, breed them for amusement and pleasure.

The most civilised of all these nations are they who inhabit Kent, which is entirely a maritime district, nor do they differ much from the Gallic customs. Most of the inland inhabitants do not sow corn, but live on milk and flesh, and are clad with skins. All the Britons, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which occasions a bluish colour, and thereby have a more terrible appearance in fight. They wear their hair long, and have every part of their body shaved except their head and upper lip. Ten and even twelve have wives common to them, and particularly brothers among brothers, and parents among their children; but if there be any issue by these wives, they are reputed to be the children of those by whom respectively each was first espoused when a virgin.

Military

In addition to infantry and cavalry, the Britons employed chariots in warfare, a novelty to the Romans, who used them for transport and racing. Caesar describes their use as follows:

Their mode of fighting with their chariots is this: firstly, they drive about in all directions and throw their weapons and generally break the ranks of the enemy with the very dread of their horses and the noise of their wheels; and when they have worked themselves in between the troops of horse, leap from their chariots and engage on foot. The charioteers in the meantime withdraw some little distance from the battle, and so place themselves with the chariots that, if their masters are overpowered by the number of the enemy, they may have a ready retreat to their own troops. Thus they display in battle the speed of horse, [together with] the firmness of infantry; and by daily practice and exercise attain to such expertness that they are accustomed, even on a declining and steep place, to check their horses at full speed, and manage and turn them in an instant and run along the pole, and stand on the yoke, and thence betake themselves with the greatest celerity to their chariots again.

Technology

During the civil war, Caesar made use of a kind of boat he had seen used in Britain, similar to the Irish currach or Welsh coracle. He describes them thus:

[T]he keels and ribs were made of light timber, then, the rest of the hull of the ships was wrought with wicker work, and covered over with hides.

Religion

"The institution [of Druidism] is thought to have originated in Britain, and to have been thence introduced into Gaul; and even now those who wish to become more accurately acquainted with it, generally repair thither, for the sake of learning it."

Economic resources

Caesar not only investigates this for the sake of it, but also to justify Britain as a rich source of tribute and trade:

[T]he number of cattle is great. They use either brass or iron rings, determined at a certain weight, as their money. Tin is produced in the midland regions; in the maritime, iron; but the quantity of it is small: they employ brass, which is imported. There, as in Gaul, is timber of every description, except beech and fir.

This reference to the 'midland' is inaccurate as tin production and trade occurred in the southwest of England, in Cornwall and Devon, and was what drew Pytheas and other traders. However, Caesar only penetrated to Essex and so, receiving reports of the trade whilst there, it would have been easy to perceive the trade as coming from the interior.

Outcome

Caesar made no conquests in Britain, but his enthroning of Mandubracius marked the beginnings of a system of client kingdoms there, thus bringing the island into Rome's sphere of political influence. Diplomatic and trading links developed further over the next century, opening up the possibility of permanent conquest, which was finally begun by Claudius in AD 43. In the words of Tacitus:

It was, in fact, the deified Julius who first of all Romans entered Britain with an army: he overawed the natives by a successful battle and made himself master of the coast; but it may be said that he revealed, rather than bequeathed, Britain to Rome.

Lucan's Pharsalia (II,572) makes the jibe that Caesar had:

...run away in terror from the Britons whom he had come to attack!

Caesar's pretext for the invasion was that "in almost all the wars with the Gauls succours had been furnished to our enemy from that country" with fugitives from among the Gallic Belgae fleeing to Belgic settlements in Britain, and the Veneti of Armorica, who controlled seaborne trade to the island, calling in aid from their British allies to fight for them against Caesar in 56 BC.Strabo says that the Venetic rebellion in 56 BC had been intended to prevent Caesar from travelling to Britain and disrupting their commercial activity, suggesting that the possibility of a British expedition had already been considered by then.

It may also have been a cover for investigating Britain's mineral resources and economic potential: afterwards, Cicero refers to the disappointing discovery that there was no gold or silver in the island; and Suetonius reports that Caesar was said to have gone to Britain in search of pearls.

However, it may have been an excuse to gain stature in the eyes of the Roman people, due to Pompey and Crassus' consulship. On the one hand, they were Caesar's political allies, and Crassus's son had fought under him the year before. But they were also his rivals, and had formidable reputations (Pompey was a great general, and Crassus was fabulously wealthy). Since the consuls could easily sway and buy public opinion, Caesar needed to stay in the public eye. His solution was to cross two water bodies no Roman army had attempted before: the Rhine and the English Channel.

Planning and reconnaissance

Caesar summoned merchants who traded with the island, but they were unable or unwilling to give him any useful information about the inhabitants and their military tactics, or about harbours he could use, presumably not wanting to lose their monopoly on cross-channel trade. He sent a tribune, Gaius Volusenus, to scout the coast in a single warship. He probably examined the Kent coast between Hythe and Sandwich, but was unable to land, since he "did not dare leave his ship and entrust himself to the barbarians", and after five days returned to give Caesar what intelligence he had managed to gather.

By then, ambassadors from some of the British states, warned by merchants of the impending invasion, had arrived promising their submission. Caesar sent them back, along with his ally Commius, king of the Belgae Atrebates, to use their influence to win over as many other states as possible.

He gathered a fleet consisting of eighty transport ships, sufficient to carry two legions (Legio VII and Legio X), and an unknown number of warships under a quaestor, at an unnamed port in the territory of the Morini, almost certainly Portus Itius (Saint-Omer). Another eighteen transports of cavalry were to sail from a different port, probably Ambleteuse. These ships may have been triremes or biremes, or may have been adapted from Venetic designs Caesar had seen previously, or may even have been requisitioned from the Veneti and other coastal tribes.

In late summer 55 BC, even though it was late in the campaigning season, Caesar decided to embark for Britain.

Landing

Clearly in a hurry, Caesar himself left a garrison at the port and set out "at the third watch" (well after midnight) on 23 August with the legions so that they would arrive at dawn, leaving the cavalry to march to their ships, embark, and join him as soon as possible. In light of later events, leaving without the cavalry was either a tactical mistake or (along with the fact that the legions came over without baggage or heavy siege gear) confirms the invasion was not intended for complete conquest.

Caesar initially tried to land but when he came in sight of shore, the massed forces of the Britons gathered on the overlooking hills dissuaded him from landing there. After waiting there at anchor "until the ninth hour" (about 3pm) waiting for his supply ships from the second port to come up and meanwhile convening a council of war, he ordered the fleet to sail north-east along the coast to an open beach probably at Ebbsfleet.

The Britons had kept pace and fielded an impressive force, including cavalry and chariots, and the legions were hesitant to go ashore. To make matters worse, the loaded Roman ships were too low in the water to go close inshore and the troops had to disembark in deep water, all the while attacked by the enemy from the shallows. Eventually, the legion's standard bearer jumped into the sea and waded to shore. To have the legion's standard fall in combat was the greatest humiliation, and the men disembarked to protect the standard bearer. After some delay, a battle line was finally formed, and the Britons withdrew. The cavalry auxiliaries were unable to make the crossing despite several attempts and so Caesar could not chase down the Britons.

Beach-head

Recent archaeology by the University of Leicester indicates that the likely landing beach was at Ebbsfleet in Pegwell Bay where artefacts and massive earthworks dating from this period have been exposed. If Caesar had as large a fleet with him as has been suggested, then it is possible that the beaching of ships would have been spread out over a number of miles stretching from Walmer towards Pegwell Bay.

The site at Ebbsfleet is a defensive enclosure today about 1 km from the sea due to siltation of the former Wantsum Channel but in ancient times was on peninsula projecting into the channel. The defensive ditch enclosed an area of over 20 ha on the shore.

Skirmishes

The Romans established a camp and received ambassadors and had Commius, who had been arrested as soon as he had arrived in Britain, returned to them. Caesar claims he was negotiating from a position of strength and that the British leaders, blaming their attacks on him on the common people, were in only four days awed into giving hostages, some immediately, some as soon as they could be brought from inland, and disbanding their army. However, after his cavalry had come within sight of the beachhead but then been scattered and turned back to Gaul by storms, and with food running short, Caesar was taken by surprise by high British tides and a storm. His beached warships filled with water, and his transports, riding at anchor, were driven against each other. Some ships were wrecked, and many others were rendered unseaworthy by the loss of rigging or other vital equipment, threatening the return journey.

Realising this and hoping to keep Caesar in Britain over the winter and thus starve him into submission, the Britons renewed the attack, ambushing one of the legions as it foraged near the Roman camp. The foraging party was relieved by the remainder of the Roman force and the Britons were again driven off, only to regroup after several days of storms with a larger force to attack the Roman camp. This attack was driven off fully, in a bloody rout, with improvised cavalry that Commius had gathered from pro-Roman Britons and a Roman scorched earth policy.

The campaigning season was now nearly over, and the legions were in no condition to winter on the coast of Kent. Caesar withdrew back across the Channel with as many of the ships as could be repaired with flotsam from the wrecked ships.

Conclusion

Caesar once again narrowly escaped disaster. Taking an understrength army with few provisions to a far-off land was a poor tactical decision, which easily could have led to Caesar's defeat, yet he survived. While he had achieved no significant gains in Britain, he had accomplished a monumental feat simply by landing there. It was a fabulous propaganda victory as well, which was chronicled in Caesar's ongoing Commentarii de Bello Gallico. The writings in the Commentarii fed Rome a steady update of Caesar's exploits (with his own personal spin on events). Caesar's goal of prestige and publicity succeeded enormously: upon his return to Rome, he was hailed as a hero and given an unprecedented 20-day thanksgiving.

Second invasion (54 BC)

Preparation

Caesar's approach in the winter of 55 54 BC towards the invasion in 54 BC was far more comprehensive and successful than his initial expedition. New ships had been built over the winter, using experience of Venetic shipbuilding technology being broader and lower for easier beaching, and Caesar now took 800 ships, five legions (instead of two) and 2,000 cavalry. He left the rest of his army in Gaul to keep order. Caesar took with him a good number of Gallic chiefs whom he considered untrustworthy so he could keep an eye on them.

This time he named Portus Itius as the departure point.

Crossing and landing

Titus Labienus was left at Portus Itius to oversee regular food transports from there to the British beachhead. The military ships were joined by a flotilla of trading ships captained by Romans and provincials from across the empire, and local Gauls, hoping to cash in on the trading opportunities. It seems more likely that the figure Caesar quotes for the fleet (800 ships) include these traders and the troop-transports, rather than the troop-transports alone.

The Roman fleet sailed from France in the evening so that the army could land in daylight. They hoped to use the wind to help cross the Channel but midnight the wind dropped and the channel tide carried them too far northeast and at sunrise they saw Britain in the distance on their left. They managed to row and use the reversing tide to arrive at the place identified as the best landing-place the previous year.

The Britons had gathered to oppose the landing but as Caesar states, intimidated by the size of the fleet, withdrew 'and concealed themselves on the high ground' perhaps to give them time to gather their forces. Caesar landed and immediately went to find the Britons army.

Kent campaign

Upon landing, Caesar left Quintus Atrius in charge of the beach-head with an equivalent of a legion to build and defend the base. He then made an immediate night march 12 mi (19 km) inland, where he encountered the British forces at a river crossing, probably somewhere on the River Stour. The Britons attacked but were repulsed, and attempted to regroup at a fortified place in the forests, possibly the hillfort at Bigbury Wood, Kent, but were again defeated and scattered. As it was late in the day and Caesar was unsure of the territory, he called off the pursuit and made camp.

However, the next morning, as he prepared to advance further, Caesar received word from Atrius that, once again, his ships at anchor had been dashed against each other in a storm and suffered considerable damage. About forty, he says, were lost. The Romans were unused to Atlantic and Channel tides and storms, but nevertheless, considering the damage he had sustained the previous year, this was poor planning on Caesar's part. However, Caesar may have exaggerated the number of ships wrecked to magnify his own achievement in rescuing the situation. He returned to the coast, recalling the legions that had gone ahead, and immediately set about repairing his fleet. His men worked day and night for approximately ten days, beaching and repairing the ships, and building a fortified camp around them. Word was sent to Labienus to send more ships.

Caesar was on the coast on 1 September, from where he wrote a letter to Cicero. News must have reached Caesar at this point of the death of his daughter Julia, as Cicero refrained from replying "on account of his mourning".

March inland

Caesar then returned to the Stour crossing and found the Britons had massed their forces there. Cassivellaunus, a warlord from north of the Thames, had previously been at war with most of the British tribes. He had recently overthrown the king of the powerful Trinovantes and forced his son, Mandubracius, into exile. But now, facing invasion, the Britons had appointed Cassivellaunus to lead their combined forces. After several indecisive skirmishes, during which a Roman tribune, Quintus Laberius Durus, was killed, the Britons attacked a foraging party of three legions under Gaius Trebonius, but were repulsed and routed by the pursuing Roman cavalry.

Cassivellaunus realised he could not defeat Caesar in a pitched battle. Disbanding the majority of his force and relying on the mobility of his 4,000 chariots and superior knowledge of the terrain, he used guerrilla tactics to slow the Roman advance. By the time Caesar reached the Thames, the one fordable place available to him had been fortified with sharpened stakes, both on the shore and under the water, and the far bank was defended. Second Century sources state that Caesar used a large war elephant, which was equipped with armour and carried archers and slingers in its tower, to put the defenders to flight. When this unknown creature entered the river, the Britons and their horses fled and the Roman army crossed over and entered Cassivellaunus' territory.This may be a confusion with Claudius's use of elephants during his conquest of Britain in AD 43.

The Trinovantes, whom Caesar describes as the most powerful tribe in the region, and who had recently suffered at Cassivellaunus' hands, sent ambassadors, promising him aid and provisions. Mandubracius, who had accompanied Caesar, was restored as their king, and the Trinovantes provided grain and hostages. Five further tribes, the Cenimagni, Segontiaci, Ancalites, Bibroci and Cassi, surrendered to Caesar, and revealed to him the location of Cassivellaunus' stronghold, possibly the hill fort at Wheathampstead, which he proceeded to put under siege.

Cassivellaunus sent word to his allies in Kent, Cingetorix, Carvilius, Taximagulus and Segovax, described as the "four kings of Cantium", to stage a diversionary attack on the Roman beach-head to draw Caesar off, but this attack failed, and Cassivellaunus sent ambassadors to negotiate a surrender. Caesar was eager to return to Gaul for the winter due to growing unrest there, and an agreement was mediated by Commius. Cassivellaunus gave hostages, agreed to an annual tribute, and undertook not to make war against Mandubracius or the Trinovantes. Caesar wrote to Cicero on 26 September, confirming the result of the campaign, with hostages but no booty taken, and that his army was about to return to Gaul.He then left, leaving not a single Roman soldier in Britain to enforce his settlement. Whether the tribute was ever paid is unknown.

Caesar extracted payment of grain, slaves, and an annual tribute to Rome. However, Britain was not particularly rich at the time; Marcus Cicero summed up Roman sentiment by saying, "It's also been established that there isn't a scrap of silver in the island and no hope of booty except for slaves and I don't suppose you're expecting them to know much about literature or music!" Regardless, this second trip to Britain was a true invasion, and Caesar achieved his goals. One interpretation is that he had beaten the Britons and extracted tribute; they were now effectively Roman subjects. Caesar was lenient towards the tribes as he needed to leave before the stormy season set in, which would make crossing the channel impossible.

However, another interpretation of the details is that Caesar had made a weakly enforced treaty with the Catuvellauni, suggesting that a decisive victory did not occur upon the Britons. Caesar achieving popularity with the Roman peoples, and Cassivellaunus' achievement of the maintained autonomy of the Britons. This is evidenced via the next identifiable king of the Trinovantes, known from numismatic evidence, was Addedomarus, who took power c. 20 15 BC, and moved the tribe's capital to Camulodunum. For a brief period c. 10 BC Tasciovanus of the Catuvellauni issued coins from Camulodunum, suggesting that he conquered the Trinobantes in direct violation of the treaty.

Aftermath

Commius later switched sides, fighting in Vercingetorix's rebellion. After a number of unsuccessful engagements with Caesar's forces, he cut his losses and fled to Britain. Sextus Julius Frontinus, in his Strategemata, describes how Commius and his followers, with Caesar in pursuit, boarded their ships. Although the tide was out and the ships still beached, Commius ordered the sails raised. Caesar, still some distance away, assumed the ships were afloat and called off the pursuit. John Creighton believes that this anecdote was a legend, and that Commius was sent to Britain as a friendly king as part of his truce with Mark Antony. Commius established a dynasty in the Hampshire area, known from coins of Gallo-Belgic type. Verica, the king whose exile prompted Claudius's conquest of AD 43, styled himself a son of Commius.

Discoveries about Britain

As well as noting elements of British warfare, particularly the use of chariots, which were unfamiliar to his Roman audience, Caesar also aimed to impress them by making further geographical, meteorological and ethnographic investigations of Britain. He probably gained these by enquiry and hearsay rather than direct experience, as he did not penetrate that far into the interior, and most historians would be wary of applying them beyond the tribes with whom he came into direct contact.

Geographical and meteorological

Caesar's first-hand discoveries were limited to east Kent and the Thames Valley, but he was able to provide a description of the island's geography and meteorology. Though his measurements are not wholly accurate, and may owe something to Pytheas, his general conclusions even now seem valid:

The climate is more temperate than in Gaul, the colds being less severe.

The island is triangular in its form, and one of its sides is opposite to Gaul. One angle of this side, which is in Kent, whither almost all ships from Gaul are directed, [looks] to the east; the lower looks to the south. This side extends about 500 miles. Another side lies toward Hispania and the west, on which part is Ireland, less, as is reckoned, than Britain, by one half: but the passage from it into Britain is of equal distance with that from Gaul. In the middle of this voyage, is an island, which is called Mona: many smaller islands besides are supposed to lie there, of which islands some have written that at the time of the winter solstice it is night there for thirty consecutive days. We, in our inquiries about that matter, ascertained nothing, except that, by accurate measurements with water, we perceived the nights to be shorter there than on the continent. The length of this side, as their account states, is 700 miles. The third side is toward the north, to which portion of the island no land is opposite; but an angle of that side looks principally toward Germany. This side is considered to be 800 miles in length. Thus the whole island is about 2,000 miles in circumference.

No information about harbours or other landing-places was available to the Romans before Caesar's expeditions, so Caesar was able to make discoveries of benefit to Roman military and trading interests. Volusenus's reconnaissance voyage before the first expedition apparently identified the natural harbour at Dubris (Dover), although Caesar was prevented from landing there and forced to land on an open beach, as he did again the following year, perhaps because Dover was too small for his much larger forces. The great natural harbours further up the coast at Rutupiae (Richborough), which were used by Claudius for his invasion 100 years later, were not used on either occasion. Caesar may have been unaware of them, may have chosen not to use them, or they may not have existed in a form suitable for sheltering and landing such a large force at that time. Present knowledge of the period geomorphology of the Wantsum Channel that created that haven is limited.

By Claudius's time Roman knowledge of the island would have been considerably increased by a century of trade and diplomacy, and four abortive invasion attempts. However, it is likely that the intelligence gathered in 55 and 54 BC would have been retained in the now-lost state records in Rome, and been used by Claudius in the planning of his landings.

Ethnography

The Britons are defined as typical barbarians, with polygamy and other exotic social habits, similar in many ways to the Gauls, yet as brave adversaries whose crushing can bring glory to a Roman:

The interior portion of Britain is inhabited by those of whom they say that it is handed down by tradition that they were born in the island itself: the maritime portion by those who had passed over from the country of the Belgae for the purpose of plunder and making war; almost all of whom are called by the names of those states from which being sprung they went thither, and having waged war, continued there and began to cultivate the lands. The number of the people is countless, and their buildings exceedingly numerous, for the most part very like those of the Gauls... They do not regard it lawful to eat the hare, and the cock, and the goose; they, however, breed them for amusement and pleasure.

The most civilised of all these nations are they who inhabit Kent, which is entirely a maritime district, nor do they differ much from the Gallic customs. Most of the inland inhabitants do not sow corn, but live on milk and flesh, and are clad with skins. All the Britons, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which occasions a bluish colour, and thereby have a more terrible appearance in fight. They wear their hair long, and have every part of their body shaved except their head and upper lip. Ten and even twelve have wives common to them, and particularly brothers among brothers, and parents among their children; but if there be any issue by these wives, they are reputed to be the children of those by whom respectively each was first espoused when a virgin.

Military

In addition to infantry and cavalry, the Britons employed chariots in warfare, a novelty to the Romans, who used them for transport and racing. Caesar describes their use as follows:

Their mode of fighting with their chariots is this: firstly, they drive about in all directions and throw their weapons and generally break the ranks of the enemy with the very dread of their horses and the noise of their wheels; and when they have worked themselves in between the troops of horse, leap from their chariots and engage on foot. The charioteers in the meantime withdraw some little distance from the battle, and so place themselves with the chariots that, if their masters are overpowered by the number of the enemy, they may have a ready retreat to their own troops. Thus they display in battle the speed of horse, [together with] the firmness of infantry; and by daily practice and exercise attain to such expertness that they are accustomed, even on a declining and steep place, to check their horses at full speed, and manage and turn them in an instant and run along the pole, and stand on the yoke, and thence betake themselves with the greatest celerity to their chariots again.

Technology

During the civil war, Caesar made use of a kind of boat he had seen used in Britain, similar to the Irish currach or Welsh coracle. He describes them thus:

[T]he keels and ribs were made of light timber, then, the rest of the hull of the ships was wrought with wicker work, and covered over with hides.

Religion

"The institution [of Druidism] is thought to have originated in Britain, and to have been thence introduced into Gaul; and even now those who wish to become more accurately acquainted with it, generally repair thither, for the sake of learning it."

Economic resources

Caesar not only investigates this for the sake of it, but also to justify Britain as a rich source of tribute and trade:

[T]he number of cattle is great. They use either brass or iron rings, determined at a certain weight, as their money. Tin is produced in the midland regions; in the maritime, iron; but the quantity of it is small: they employ brass, which is imported. There, as in Gaul, is timber of every description, except beech and fir.

This reference to the 'midland' is inaccurate as tin production and trade occurred in the southwest of England, in Cornwall and Devon, and was what drew Pytheas and other traders. However, Caesar only penetrated to Essex and so, receiving reports of the trade whilst there, it would have been easy to perceive the trade as coming from the interior.

Outcome

Caesar made no conquests in Britain, but his enthroning of Mandubracius marked the beginnings of a system of client kingdoms there, thus bringing the island into Rome's sphere of political influence. Diplomatic and trading links developed further over the next century, opening up the possibility of permanent conquest, which was finally begun by Claudius in AD 43. In the words of Tacitus:

It was, in fact, the deified Julius who first of all Romans entered Britain with an army: he overawed the natives by a successful battle and made himself master of the coast; but it may be said that he revealed, rather than bequeathed, Britain to Rome.

Lucan's Pharsalia (II,572) makes the jibe that Caesar had:

...run away in terror from the Britons whom he had come to attack!

Some will say the following Emperors Conquered Britain, not exactly!

NO!

Marcus Junius Brutus 85-42BC

NO!

NO!

Marcus Junius Brutus, the famed Roman senator and one of Julius Caesar's assassins, did not conquer Britain. Brutus is primarily known for his role in the assassination of Caesar in 44 BCE and his subsequent involvement in the Roman civil war.

However, there is a legendary Brutus connected to Britain—but not the historical one. According to medieval British legend, as recounted in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain), a mythical figure named Brutus of Troy is said to have been the founder of Britain. This Brutus was purportedly a descendant of the Trojan hero Aeneas and is credited with naming the island "Britain" after himself. This legend, however, is not based on historical fact but rather on medieval myth-making.

So, while the historical Brutus stayed firmly within the Roman world, the legendary Brutus exists in the realm of British folklore.

Following Julius Caesar's invasions of Britain in 54 BC, some southern British chiefdoms had become allies of the Romans. The exile of their ally Verica gave the Romans a pretext for invasion. The Roman army was recruited in Italia, Hispania, and Gaul and used the newly-formed fleet Classis Britannica. Under their general Aulus Plautius, the Romans pushed inland from the southeast, defeating the Britons in the Battle of the Medway. By AD 47, the Romans held the lands southeast of the Fosse Way. British resistance was led by the chieftain Caratacus until his defeat in AD 50. The isle of Mona, a stronghold of the druids, was attacked in AD 60. This was interrupted by an uprising led by Boudica, in which the Britons destroyed Camulodunum, Verulamium and Londinium. The Romans put down the rebellion.

In common with other regions on the edge of the empire, Britain had enjoyed diplomatic and trading links with the Romans in the century since Julius Caesar's expeditions in 55 and 54 BC, and Roman economic and cultural influence was a significant part of the British late pre-Roman Iron Age, especially in the south.

Between 55 BC and the 40s AD, the status quo of tribute, hostages, and client states without direct military occupation, begun by Caesar's invasions of Britain, largely remained intact. Augustus prepared invasions in 34 BC, 27 BC and 25 BC. The first and third were called off due to revolts elsewhere in the empire, the second because the Britons seemed ready to come to terms. According to Augustus's Res Gestae, two British kings, Dubnovellaunus and Tincomarus, fled to Rome as supplicants during his reign, and Strabo's Geographica, written during this period, says Britain paid more in customs and duties than could be raised by taxation if the island were conquered.

By the 40s AD, the political situation within Britain was in ferment. The Catuvellauni had displaced the Trinovantes as the most powerful kingdom in south-eastern Britain, taking over the former Trinovantian capital of Camulodunum (Colchester). The Atrebates tribe whose capital was at Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) had friendly trade and diplomatic links with Rome and Verica was recognised by Rome as their king, but Caratacus' Catuvellauni conquered the entire kingdom some time after AD 40 and Verica was expelled from Britain.

Caligula may have planned a campaign against the Britons in AD 40, but its execution was unclear: according to Suetonius' The Twelve Caesars, he drew up his troops in battle formation facing the English Channel and, once his forces had become quite confused, ordered them to gather seashells, referring to them as "plunder from the ocean due to the Capitol and the Palace". Alternatively, he may have told them to gather "huts", since the word musculi was also soldier's slang for engineers' huts and Caligula himself was very familiar with the Empire's soldiers. In any case this readied the troops and facilities that would make Claudius' invasion possible three years later. For example, Caligula built a lighthouse at Bononia (modern Boulogne-sur-Mer), the Tour d'Ordre, that provided a model for the one built soon after at Dubris (Dover).

In 43, possibly by reassembling Caligula's troops from 40, Claudius mounted an invasion force under overall charge of Aulus Plautius, a distinguished senator. A pretext of the invasion was to reinstate Verica, the exiled king of the Atrebates.

It is unclear how many legions were sent: only the Legio II Augusta, commanded by future emperor Vespasian, was directly attested to have taken part.

The IX Hispana, the XIV Gemina (later styled Martia Victrix) and the XX (later styled Valeria Victrix) are known to have served during the Boudican revolt of 60 61, and were probably there since the initial invasion, but the Roman army was flexible, with cohorts and auxiliary units being moved around whenever necessary.

Three other men of appropriate rank to command legions are known from the sources to have been involved in the invasion. Cassius Dio mentions Gnaeus Hosidius Geta, who probably led the IX Hispana, and Vespasian's brother Titus Flavius Sabinus the Younger. He wrote that Sabinus was Vespasian's lieutenant, but as Sabinus was the older brother and preceded Vespasian into public life, he could hardly have been a military tribune. Eutropius mentions Gnaeus Sentius Saturninus, although as a former consul he may have been too senior, and perhaps accompanied Claudius later.

The main invasion force under Aulus Plautius crossed in three divisions. The port of departure is usually taken to have been Bononia (Boulogne), and the main landing at Rutupiae (Richborough, on the east coast of Kent). Neither of these locations is certain. Dio does not mention the port of departure, and although Suetonius says that the secondary force under Claudius sailed from Boulogne it does not necessarily follow that the entire invasion force did. Richborough had a large natural harbour, which would have been suitable, and archaeology shows Roman military occupation at about the right time. However Dio says the Romans sailed east to west, and a journey from Boulogne to Richborough is south to north. Some historians suggest a sailing from Boulogne to the Solent, landing in the vicinity of Noviomagus (Chichester) or Southampton, in territory formerly ruled by Verica.

British resistance was led by Togodumnus and Caratacus, sons of the late king of the Catuvellauni, Cunobeline. A substantial British force met the Romans at a river crossing thought to be near Rochester on the River Medway. The Battle of the Medway raged for two days. Gnaeus Hosidius Geta was almost captured, but recovered and turned the battle so decisively that he was awarded the Roman triumph. At least one division of auxiliary Batavian troops swam across the river as a separate force.

The British were pushed back to the Thames. They were pursued by the Romans across the river, causing some Roman losses in the marshes of Essex. Whether the Romans made use of an existing bridge for this purpose or built a temporary one is uncertain.

Togodumnus died shortly after the battle on the Thames. Plautius halted and sent word for Claudius to join him for the final push. Cassius Dio presents this as Plautius needing the emperor's assistance to defeat the resurgent British, who were determined to avenge Togodumnus. However, Claudius was no military man. The Praetorian cohorts accompanied Emperor Claudius to Britain in AD 43. The Arch of Claudius in Rome says he received the surrender of eleven British kings with no losses, and Suetonius' The Twelve Caesars says that Claudius received the surrender of the Britons without battle or bloodshed. It is likely that the Catuvellauni were already as good as beaten, allowing the emperor to appear as conqueror on the final march on Camulodunum. Cassius Dio relates that he brought war elephants and heavy armaments which would have overawed any remaining native resistance. Eleven tribes of South East Britain surrendered to Claudius and the Romans prepared to move further west and north. The Romans established their new capital at Camulodunum and Claudius returned to Rome to celebrate his victory. Caratacus escaped with his family, retainers, and treasure, to continue his resistance further west.

After the invasion, Verica may have been restored as king of the Atrebates although by this time he would have been very elderly. In any case a new ruler for their region, Cogidubnus, soon appeared as his heir and as king of a number of territories following the first stage of the conquest as a reward as a Roman ally.

AD 44 60

Roman campaigns from AD 43 to 60

Forts of the conquest period of Roman Britain

Vespasian took a force westwards, subduing tribes and capturing oppida settlements as he went. The force proceeded at least as far as Exeter, which became a base for the Roman legion, Legio II Augusta, from 55 until 75. Legio IX Hispana was sent north towards Lincoln (Latin: Lindum Colonia) and by 47 it is likely that an area south of a line from the Humber to the Severn Estuary was under Roman control. That this line is followed by the Roman road of the Fosse Way has led many historians to debate the route's role as a convenient frontier during the early occupation. It is unlikely that the border between Roman and Iron Age Britain was fixed with modern precision during this period.

Late in 47 the new governor of Britain, Publius Ostorius Scapula, began a campaign against the tribes of modern-day Wales, and the Cheshire Gap. The Silures of southeast Wales caused considerable problems to Ostorius and fiercely defended their border country. Caratacus himself led this guerilla campaign but was defeated when he finally chose to offer a decisive battle; he fled to the Roman client tribe of the Brigantes who occupied the Pennines. Their queen Cartimandua was unable or unwilling to protect him however, given her own accommodation with the Romans, and handed him over to the invaders. Ostorius died and was replaced by Aulus Didius Gallus who brought what are now the Welsh borders under control but did not move further north or west, probably because Claudius was keen to avoid what he considered a difficult and drawn-out war for little material gain in the mountainous terrain of upland Britain. When Nero became emperor in 54, he seems to have decided to continue the invasion and appointed Quintus Veranius as governor, a man experienced in dealing with the troublesome hill tribes of Anatolia. Veranius and his successor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus mounted a successful campaign across North Wales, famously killing many druids when he invaded the island of Anglesey in 60. Final occupation of Wales was postponed however when the rebellion of Boudica forced the Romans to return to the south east in 60 or 61.

AD 60 78

Following the successful suppression of Boudica's uprising in 60 or 61, new Roman governors continued the conquest by edging north.

The leader of the Brigantes was queen Cartimandua. Her husband was Venutius; one speculation is that he might have been a Carvetian and may therefore have been responsible for the incorporation of Cumbria into a Brigantian federation whose territory straddled Britain along the Solway-Tyne line. Cartimandua may have ruled the Brigantian peoples east of the Pennines (possibly with a centre at Stanwick, Yorkshire), while Venutius was the chief of the Brigantes (or Carvetii) west of the Pennines in Cumbria (with a possible centre based at Clifton Dykes): 16 17 Cartimandua was forced to ask for Roman aid following a rebellion by Venutius in 69. The Romans evacuated Cartimandua leaving Venutius in power.

Tacitus says that in 71 Quintus Petillius Cerialis (governor AD 71 74) waged a successful war against the Brigantes. Tacitus praises both Cerialis and his successor, Julius Frontinus (governor 75 78).

Much of the conquest of the north may have been achieved under the governorships of Vettius Bolanus (governor AD 69 71), and of Cerialis. From other sources, it seems that Bolanus had possibly dealt with Venutius and penetrated into Scotland, and evidence from the carbon-dating of the gateway timbers of the Roman fort at Carlisle (Luguvalium) suggests that they were felled in AD 72, during the governorship of Cerialis: 28 35 Lead ingots from Deva Victrix, the Roman fortress at Chester, indicate that construction there was probably under way by AD 74. Nevertheless, Gnaeus Julius Agricola played his part in the west as commander of the legion XX Valeria Victrix (71 73), while Cerialis led the IX Hispania in the east. In addition, the Legio II Adiutrix sailed from Chester up river estuaries to surprise the enemy.

The western thrust was started from Lancaster, where there is evidence of a Cerialian foundation, and followed the line of the Lune and Eden river valleys through Low Borrow Bridge and Brougham (Brocavum). On the Cumbrian coast, Ravenglass and Blennerhasset were probably involved from evidence of one of the earliest Roman occupations in Cumbria. Beckfoot and Maryport may also have featured early on. At some point between 72 and 73, part of Cerialis's force moved across the Stainmore Pass from Corbridge westwards to join Agricola, as evidenced by campaign camps (which may have been previously set up by Bolanus) at Rey Cross, Crackenthorpe, Kirkby Thore and Plumpton Head. Signal- or watch-towers are also in evidence across the Stainmore area: Maiden Castle, Bowes Moor and Roper Castle, for example: 29 36 The two forces then moved up from the vicinity of Penrith to Carlisle, establishing the fort there in AD 72 73.

Frontinus was sent into Roman Britain in 74 to succeed Cerialis as governor.

He returned to the conquest of Wales interrupted years before and with steady and successful progress finally subdued the Silures (around 76) and other hostile tribes, establishing a new base at Caerleon for Legio II Augusta (Isca Augusta) in 75 and a network of smaller forts 15 20 kilometres (9 12 mi) apart for his auxiliary units. During his tenure, he probably established the fort at Pumsaint in west Wales, largely to exploit the gold deposits at Dolaucothi. He left the post in 78, and was later appointed water commissioner in Rome.

However, there is a legendary Brutus connected to Britain—but not the historical one. According to medieval British legend, as recounted in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain), a mythical figure named Brutus of Troy is said to have been the founder of Britain. This Brutus was purportedly a descendant of the Trojan hero Aeneas and is credited with naming the island "Britain" after himself. This legend, however, is not based on historical fact but rather on medieval myth-making.

So, while the historical Brutus stayed firmly within the Roman world, the legendary Brutus exists in the realm of British folklore.

Following Julius Caesar's invasions of Britain in 54 BC, some southern British chiefdoms had become allies of the Romans. The exile of their ally Verica gave the Romans a pretext for invasion. The Roman army was recruited in Italia, Hispania, and Gaul and used the newly-formed fleet Classis Britannica. Under their general Aulus Plautius, the Romans pushed inland from the southeast, defeating the Britons in the Battle of the Medway. By AD 47, the Romans held the lands southeast of the Fosse Way. British resistance was led by the chieftain Caratacus until his defeat in AD 50. The isle of Mona, a stronghold of the druids, was attacked in AD 60. This was interrupted by an uprising led by Boudica, in which the Britons destroyed Camulodunum, Verulamium and Londinium. The Romans put down the rebellion.

In common with other regions on the edge of the empire, Britain had enjoyed diplomatic and trading links with the Romans in the century since Julius Caesar's expeditions in 55 and 54 BC, and Roman economic and cultural influence was a significant part of the British late pre-Roman Iron Age, especially in the south.

Between 55 BC and the 40s AD, the status quo of tribute, hostages, and client states without direct military occupation, begun by Caesar's invasions of Britain, largely remained intact. Augustus prepared invasions in 34 BC, 27 BC and 25 BC. The first and third were called off due to revolts elsewhere in the empire, the second because the Britons seemed ready to come to terms. According to Augustus's Res Gestae, two British kings, Dubnovellaunus and Tincomarus, fled to Rome as supplicants during his reign, and Strabo's Geographica, written during this period, says Britain paid more in customs and duties than could be raised by taxation if the island were conquered.

By the 40s AD, the political situation within Britain was in ferment. The Catuvellauni had displaced the Trinovantes as the most powerful kingdom in south-eastern Britain, taking over the former Trinovantian capital of Camulodunum (Colchester). The Atrebates tribe whose capital was at Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) had friendly trade and diplomatic links with Rome and Verica was recognised by Rome as their king, but Caratacus' Catuvellauni conquered the entire kingdom some time after AD 40 and Verica was expelled from Britain.

Caligula may have planned a campaign against the Britons in AD 40, but its execution was unclear: according to Suetonius' The Twelve Caesars, he drew up his troops in battle formation facing the English Channel and, once his forces had become quite confused, ordered them to gather seashells, referring to them as "plunder from the ocean due to the Capitol and the Palace". Alternatively, he may have told them to gather "huts", since the word musculi was also soldier's slang for engineers' huts and Caligula himself was very familiar with the Empire's soldiers. In any case this readied the troops and facilities that would make Claudius' invasion possible three years later. For example, Caligula built a lighthouse at Bononia (modern Boulogne-sur-Mer), the Tour d'Ordre, that provided a model for the one built soon after at Dubris (Dover).

In 43, possibly by reassembling Caligula's troops from 40, Claudius mounted an invasion force under overall charge of Aulus Plautius, a distinguished senator. A pretext of the invasion was to reinstate Verica, the exiled king of the Atrebates.

It is unclear how many legions were sent: only the Legio II Augusta, commanded by future emperor Vespasian, was directly attested to have taken part.

The IX Hispana, the XIV Gemina (later styled Martia Victrix) and the XX (later styled Valeria Victrix) are known to have served during the Boudican revolt of 60 61, and were probably there since the initial invasion, but the Roman army was flexible, with cohorts and auxiliary units being moved around whenever necessary.

Three other men of appropriate rank to command legions are known from the sources to have been involved in the invasion. Cassius Dio mentions Gnaeus Hosidius Geta, who probably led the IX Hispana, and Vespasian's brother Titus Flavius Sabinus the Younger. He wrote that Sabinus was Vespasian's lieutenant, but as Sabinus was the older brother and preceded Vespasian into public life, he could hardly have been a military tribune. Eutropius mentions Gnaeus Sentius Saturninus, although as a former consul he may have been too senior, and perhaps accompanied Claudius later.

The main invasion force under Aulus Plautius crossed in three divisions. The port of departure is usually taken to have been Bononia (Boulogne), and the main landing at Rutupiae (Richborough, on the east coast of Kent). Neither of these locations is certain. Dio does not mention the port of departure, and although Suetonius says that the secondary force under Claudius sailed from Boulogne it does not necessarily follow that the entire invasion force did. Richborough had a large natural harbour, which would have been suitable, and archaeology shows Roman military occupation at about the right time. However Dio says the Romans sailed east to west, and a journey from Boulogne to Richborough is south to north. Some historians suggest a sailing from Boulogne to the Solent, landing in the vicinity of Noviomagus (Chichester) or Southampton, in territory formerly ruled by Verica.

British resistance was led by Togodumnus and Caratacus, sons of the late king of the Catuvellauni, Cunobeline. A substantial British force met the Romans at a river crossing thought to be near Rochester on the River Medway. The Battle of the Medway raged for two days. Gnaeus Hosidius Geta was almost captured, but recovered and turned the battle so decisively that he was awarded the Roman triumph. At least one division of auxiliary Batavian troops swam across the river as a separate force.

The British were pushed back to the Thames. They were pursued by the Romans across the river, causing some Roman losses in the marshes of Essex. Whether the Romans made use of an existing bridge for this purpose or built a temporary one is uncertain.

Togodumnus died shortly after the battle on the Thames. Plautius halted and sent word for Claudius to join him for the final push. Cassius Dio presents this as Plautius needing the emperor's assistance to defeat the resurgent British, who were determined to avenge Togodumnus. However, Claudius was no military man. The Praetorian cohorts accompanied Emperor Claudius to Britain in AD 43. The Arch of Claudius in Rome says he received the surrender of eleven British kings with no losses, and Suetonius' The Twelve Caesars says that Claudius received the surrender of the Britons without battle or bloodshed. It is likely that the Catuvellauni were already as good as beaten, allowing the emperor to appear as conqueror on the final march on Camulodunum. Cassius Dio relates that he brought war elephants and heavy armaments which would have overawed any remaining native resistance. Eleven tribes of South East Britain surrendered to Claudius and the Romans prepared to move further west and north. The Romans established their new capital at Camulodunum and Claudius returned to Rome to celebrate his victory. Caratacus escaped with his family, retainers, and treasure, to continue his resistance further west.

After the invasion, Verica may have been restored as king of the Atrebates although by this time he would have been very elderly. In any case a new ruler for their region, Cogidubnus, soon appeared as his heir and as king of a number of territories following the first stage of the conquest as a reward as a Roman ally.

AD 44 60

Roman campaigns from AD 43 to 60

Forts of the conquest period of Roman Britain

Vespasian took a force westwards, subduing tribes and capturing oppida settlements as he went. The force proceeded at least as far as Exeter, which became a base for the Roman legion, Legio II Augusta, from 55 until 75. Legio IX Hispana was sent north towards Lincoln (Latin: Lindum Colonia) and by 47 it is likely that an area south of a line from the Humber to the Severn Estuary was under Roman control. That this line is followed by the Roman road of the Fosse Way has led many historians to debate the route's role as a convenient frontier during the early occupation. It is unlikely that the border between Roman and Iron Age Britain was fixed with modern precision during this period.

Late in 47 the new governor of Britain, Publius Ostorius Scapula, began a campaign against the tribes of modern-day Wales, and the Cheshire Gap. The Silures of southeast Wales caused considerable problems to Ostorius and fiercely defended their border country. Caratacus himself led this guerilla campaign but was defeated when he finally chose to offer a decisive battle; he fled to the Roman client tribe of the Brigantes who occupied the Pennines. Their queen Cartimandua was unable or unwilling to protect him however, given her own accommodation with the Romans, and handed him over to the invaders. Ostorius died and was replaced by Aulus Didius Gallus who brought what are now the Welsh borders under control but did not move further north or west, probably because Claudius was keen to avoid what he considered a difficult and drawn-out war for little material gain in the mountainous terrain of upland Britain. When Nero became emperor in 54, he seems to have decided to continue the invasion and appointed Quintus Veranius as governor, a man experienced in dealing with the troublesome hill tribes of Anatolia. Veranius and his successor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus mounted a successful campaign across North Wales, famously killing many druids when he invaded the island of Anglesey in 60. Final occupation of Wales was postponed however when the rebellion of Boudica forced the Romans to return to the south east in 60 or 61.

AD 60 78

Following the successful suppression of Boudica's uprising in 60 or 61, new Roman governors continued the conquest by edging north.

The leader of the Brigantes was queen Cartimandua. Her husband was Venutius; one speculation is that he might have been a Carvetian and may therefore have been responsible for the incorporation of Cumbria into a Brigantian federation whose territory straddled Britain along the Solway-Tyne line. Cartimandua may have ruled the Brigantian peoples east of the Pennines (possibly with a centre at Stanwick, Yorkshire), while Venutius was the chief of the Brigantes (or Carvetii) west of the Pennines in Cumbria (with a possible centre based at Clifton Dykes): 16 17 Cartimandua was forced to ask for Roman aid following a rebellion by Venutius in 69. The Romans evacuated Cartimandua leaving Venutius in power.

Tacitus says that in 71 Quintus Petillius Cerialis (governor AD 71 74) waged a successful war against the Brigantes. Tacitus praises both Cerialis and his successor, Julius Frontinus (governor 75 78).

Much of the conquest of the north may have been achieved under the governorships of Vettius Bolanus (governor AD 69 71), and of Cerialis. From other sources, it seems that Bolanus had possibly dealt with Venutius and penetrated into Scotland, and evidence from the carbon-dating of the gateway timbers of the Roman fort at Carlisle (Luguvalium) suggests that they were felled in AD 72, during the governorship of Cerialis: 28 35 Lead ingots from Deva Victrix, the Roman fortress at Chester, indicate that construction there was probably under way by AD 74. Nevertheless, Gnaeus Julius Agricola played his part in the west as commander of the legion XX Valeria Victrix (71 73), while Cerialis led the IX Hispania in the east. In addition, the Legio II Adiutrix sailed from Chester up river estuaries to surprise the enemy.