Everything For The Detectorist - Reference & Timelines

Powered By Sispro1

More Indepth notes on Metals

Source: Bibliography

Source: Bibliography

United Kingdom - The Roman Empire The First to Invade Britain

The British Library is also a good source to fill in the gaps of history

For an external link click onto the banner below to go to the British Library.

For an external link click onto the banner below to go to the British Library.

Click

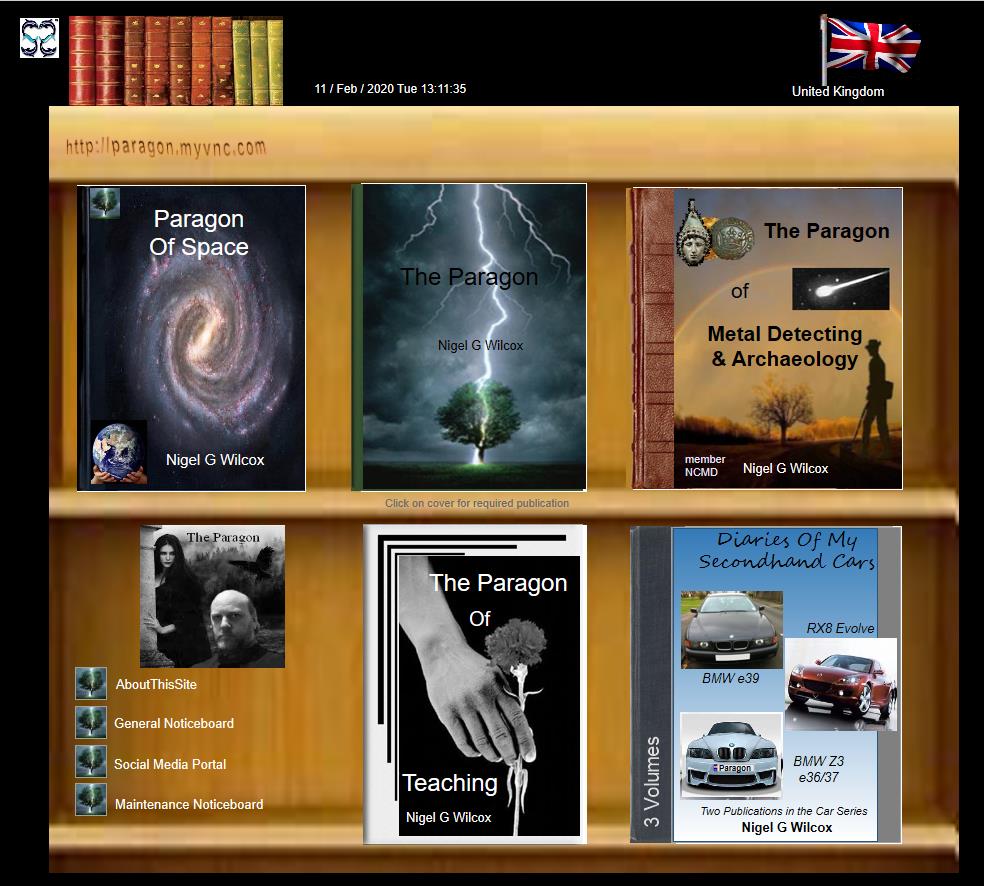

Emperors

Roman Index Menu

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

5. Menu

Pages

Member NCMD

Double click to start editing the text

Some will say the following Emperors Conquered Britain, they didn't!

End...

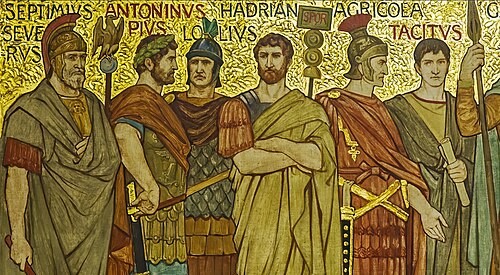

Campaigns of Agricola (AD 78–84)

Agricola's campaigns.

The new governor was Agricola, returning to Britain, and made famous through the highly laudatory biography of him written by his son-in-law, Tacitus. Arriving in mid-78, Agricola completed the conquest of Wales in defeating the Ordovices who had destroyed a cavalry ala of Roman auxiliaries stationed in their territory. Knowing the terrain from his prior military service in Britain, he was able to move quickly to subdue them. He then invaded Anglesey, forcing the inhabitants to sue for peace.

The following year he moved against the Brigantes of northern England and the Selgovae along the southern coast of Scotland, using overwhelming military power to establish Roman control.

Agricola in Caledonia

Tacitus says that after a combination of force and diplomacy quieted discontent among the Britons who had been conquered previously, Agricola built forts in their territories in 79. In 80, he marched to the Firth of Tay (some historians hold that he stopped along the Firth of Forth in that year), not returning south until 81, at which time he consolidated his gains in the new lands that he had conquered, and in the rebellious lands that he had re-conquered. In 82, he sailed to either Kintyre or the shores of Argyll, or to both. In 83 and 84, he moved north along Scotland's eastern and northern coasts using both land and naval forces, campaigning successfully against the inhabitants and winning a significant victory over the northern British peoples led by Calgacus at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Archaeology has shown the Romans built military camps in the north along Gask Ridge, controlling the glens that provided access to and from the Scottish Highlands, and also throughout the Scottish Lowlands in northeastern Scotland.

Agricola built a network of military roads and forts to secure the Roman occupation. Existing forts were strengthened and new ones planted in northeastern Scotland along the Highland Line, consolidating control of the glens that provided access to and from the Scottish Highlands. The line of military communication and supply along southeastern Scotland and northeastern England (i.e., Dere Street) was well-fortified. In southernmost Caledonia, the lands of the Selgovae (approximating to modern Dumfriesshire and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright) were heavily planted with forts, not only establishing effective control there, but also completing a military enclosure of south-central Scotland (most of the Southern Uplands, Teviotdale, and western Tweeddale). In contrast to Roman actions against the Selgovae, the territories of the Novantae, Damnonii, and Votadini were not planted with forts, and there is nothing to indicate that the Romans were at war with them. Agricola was recalled to Rome in 84.

Archaeology

In 2019 a marching camp dating to the 1st century AD, used by Roman legions during the invasion of Agricola. Clay-domed ovens and 26 fire pits dated to AD 77 90 were found loaded with burn and charcoal contents. The fire pits were 30 metres (98 feet) apart in two parallel lines. Archaeologists suggested that this site had been chosen as a strategic location for the Roman conquest of Ayrshire.

The conquest of Wales lasted until c. AD 77. Roman general Gnaeus Julius Agricola conquered much of northern Britain during the following seven years. In AD 84, Agricola defeated a Caledonian army, led by Calgacus, at the Battle of Mons Graupius. However, the Romans soon withdrew from northern Britain. After Hadrian's Wall was established as the northern border, tribes in the region repeatedly rebelled against Roman rule and forts continued to be maintained across northern Britain to protect against these attacks.

AD 84 117

Roman military organisation in the north c. 84 AD

Agricola's successors are not named in any surviving source, but it seems they were unable or unwilling to further subdue the far north. The fortress at Inchtuthil was dismantled before its completion and the other fortifications of the Gask Ridge in Perthshire, erected to consolidate the Roman presence in Scotland in the aftermath of Mons Graupius, were abandoned within the space of a few years. It is equally likely that the costs of a drawn-out war outweighed any economic or political benefit and it was more profitable to leave the Caledonians alone and only under de jure submission.

With the decline of imperial ambitions in Scotland (and Ireland) by AD 87 (the withdrawal of the 20th legion), consolidation based on the line of the Stanegate road (between Carlisle and Corbridge) was settled upon. Carlisle was the seat of a centurio regionarius (or district commissioner). When the Stanegate became the new frontier it was augmented by large forts as at Vindolanda and additional forts at half-day marching intervals were built at Newbrough, Magnis (Carvoran) and Brampton Old Church.

The period from 87 to 117 was used for consolidation and only a few sites north of the Stanegate line were maintained, while the signs are that an orderly withdrawal to the Solway-Tyne line was made.: 56

Modifications to the Stanegate line, with the reduction in the size of the forts and the addition of fortlets and watchtowers between them, seem to have taken place from the mid-90s onwards: 58 Apart from the Stanegate line, other forts existed along the Solway Coast at Beckfoot, Maryport, Burrow Walls (near the present town of Workington) and Moresby (near Whitehaven). Other forts in the region were built to consolidate Roman presence (Beckfoot for example may date from the late 1st century). A fort at Troutbeck may have been established from the period of Emperor Trajan (r. 98 117) onwards. Other forts that may have been established during this period include Ambleside (Galava), positioned to take advantage of ship-borne supply to the forts of the Lake District. From here, a road was constructed during the Trajanic period to Hardknott Roman Fort. A road between Ambleside to Old Penrith and/or Brougham, going over High Street, may also date from this period.

From AD 117

Scotland during the Roman Empire

Levels of Romanisation by area and date

Under Hadrian (r. 117 138), Roman occupation was withdrawn to a defensible frontier in the River Tyne-Solway Firth frontier area by the construction of Hadrian's Wall from around 122.

Hadrian - Hadrian In AD43 did not conquer Britain. By the time Hadrian became emperor in AD 117, Britain had already been under Roman control for several decades. The Roman conquest of Britain began in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius.

Hadrian is perhaps best known in Britain for commissioning the construction of Hadrian's Wall, a massive fortification in the north of the province (modern-day northern England) built around AD 122. The wall marked the northern boundary of the Roman Empire in Britain and was intended to control movements between Roman Britain and the lands to the north, inhabited by tribes like the Picts.

Hadrian s approach to ruling the empire emphasized consolidation and defense rather than expansion, which is why his reign is often remembered for fortifications like Hadrian's Wall.

When Antoninus Pius rose to the throne, he moved quickly to reverse the empire limit system put in place by his predecessor. Following his defeat of the Brigantes in 139 AD, Quintus Lollius Urbicus, the Roman Governor of Britannia, was ordered by Antoninus Pius to march north of Hadrian's Wall to conquer the Caledonian Lowlands which were settled by the Otadini, Selgovae, Damnonii and the Novantae, and to push the frontier further north. Lollius Urbicus moved three legions into position initially establishing his supply routes from Coria and Bremenium and moved three legions, the Legio II Augusta from Caerleon, the Legio VI Victrix from Eboracum, and the Legio XX Valeria Victrix from Deva Victrix into the theatre between 139 and 140 AD, and thereafter moved his army, a force of at least 16,500 men, north of Hadrian's Wall.

The Selgovae, having settled in the regions of present-day Kirkcudbrightshire and Dumfriesshire immediately northwest of Hadrian's Wall, were amongst the first of the Caledonian tribes to face Lollius Urbicus's legions together with the Otadini. The Romans, who were well versed in warfare on hilly terrain since their founding, moved quickly to occupy strategic points and high ground, some of which had already been fortified by the Caledonians with hill forts. One such was Burnswark Hill which was strategically located commanding the western route north further into Caledonia and where significant evidence of the battle has been found.

By 142 the Romans had occupied the entire area and had successfully moved the frontier north to the River Clyde-River Forth area when the Antonine Wall was constructed. This was abandoned in 162 and only subsequently re-occupied on an occasional basis. Meanwhile, the Romans retreated to the earlier and stronger Hadrian's Wall.

Roman troops penetrated far into the north of modern Scotland several more times. There is a greater density of Roman marching camps in Scotland than anywhere else in Europe as a result of at least four major attempts to subdue the area.

3rd and 4th centuries

The brief Roman invasion of Caledonia (208 211)

The most notable later expedition was in 209 when the emperor Septimius Severus, claiming to be provoked by the belligerence of the Maeatae tribe, campaigned against the Caledonian Confederacy, a coalition of Brittonic Pictish tribes of the north of Britain. He used the three legions of the British garrison (augmented by the recently formed 2nd Parthica legion), 9000 imperial guards with cavalry support, and numerous auxiliaries supplied from the sea by the British fleet, the Rhine fleet and two fleets transferred from the Danube for the purpose. According to Dio Cassius, he inflicted genocidal depredations on the natives and incurred the loss of 50,000 of his own men to the attrition of guerrilla tactics before having to withdraw to Hadrian's Wall. He repaired and reinforced the wall with a degree of thoroughness that led most subsequent Roman authors to attribute the construction of the wall to him. During the negotiations to purchase the truce necessary to secure the Roman retreat to the wall, Septimius Severus's wife, Julia Domna, criticised the sexual morals of the Caledonian women; the wife of Argentocoxos, a Caledonian chief, replied: "We consort openly with the best of men while you allow yourselves to be debauched in private by the worst". This is the first recorded utterance confidently attributable to a native of the area now known as Scotland. The emperor Septimius Severus died at York while planning to renew hostilities, and these plans were abandoned by his son Caracalla.

Emperor Constantius came to Britain in 306, despite his poor health, with an army aiming to invade northern Britain, after the provincial defences had been rebuilt following the Carausian Revolt. Little is known of his campaigns with scant archaeological evidence, but fragmentary historical sources suggest he reached the far north of Britain and won a major battle in early summer before returning south. His son Constantine (later Constantine the Great) spent a year in northern Britain at his father's side, campaigning against the Picts beyond Hadrian's Wall in the summer and autumn.

Later excursions into Scotland by the Romans were generally limited to the scouting expeditions of exploratory in the buffer zone that developed between the walls, trading contacts, bribes to purchase truces from the natives, and eventually the spread of Christianity. The degree to which the Romans interacted with the Goidelic-speaking island of Hibernia (modern Ireland) is still unresolved amongst archaeologists in Ireland.

.

Governor Of Britain - Arriving in midsummer of 77, Agricola discovered that the Ordovices of north Wales had virtually destroyed the Roman cavalry stationed in their territory. He immediately moved against them and defeated them. His campaign then moved onto Anglesey where he subjugated the entire island. Almost two decades earlier, Governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus had attempted the same but Roman forces had to withdraw in 60 CE because of the outbreak of the Boudican rebellion.

The conquest of Wales lasted until c. AD 77. Roman general Gnaeus Julius Agricola conquered much of northern Britain during the following seven years. In AD 84, Agricola defeated a Caledonian army, led by Calgacus, at the Battle of Mons Graupius. However, the Romans soon withdrew from northern Britain. After Hadrian's Wall was established as the northern border, tribes in the region repeatedly rebelled against Roman rule and forts continued to be maintained across northern Britain to protect against these attacks.

Agricola also expanded Roman rule north into Caledonia (modern Scotland). In the summer of 79, he pushed his armies to the estuary of the river Taus, usually interpreted as the Firth of Tay, virtually unchallenged, and established some forts. Though their location is left unspecified, the close dating of the fort at Elginhaugh in Midlothian makes it a possible candidate. He established himself as a good administrator by reforming the widely corrupt corn levy as well as through his military successes. He introduced Romanising measures, encouraging communities to build towns on the Roman model and gave a Roman education to sons of native nobility; albeit, as Tacitus notes, for the cynical reason of pacifying the aggressive tribes in Britannia for the servitude of Rome.

Hibernia

In 81, Agricola "crossed in the first ship" and defeated peoples unknown to the Romans until then. Tacitus, in Chapter 24 of Agricola, does not tell us what body of water he crossed. Modern scholarship favours either the Firth of Clyde or Firth of Forth. Tacitus also mentions Hibernia, so southwest Scotland is perhaps to be preferred. The text of the Agricola has been amended here to record the Romans "crossing into trackless wastes", referring to the wilds of the Galloway peninsula. Agricola fortified the coast facing Ireland, and Tacitus recalls that his father-in-law often claimed the island could be conquered with a single legion and auxiliaries. He had given refuge to an exiled Irish king whom he hoped he might use as the excuse for conquest. This conquest never happened, but some historians believe the crossing referred to was in fact a small-scale exploratory or punitive expedition to Ireland, though no Roman camps have been identified to confirm such a suggestion.

Irish legend provides a striking parallel. Tuathal Teachtmhar, a legendary High King, is said to have been exiled from Ireland as a boy, and to have returned from Britain at the head of an army to claim the throne. The traditional date of his return is between 76 and 80, and archaeology has found Roman or Romano-British artefacts in several sites associated with Tuathal

The following year, Agricola raised a fleet and encircled the tribes beyond the Forth, and the Caledonians rose in great numbers against him. They attacked the camp of the Legio IX Hispana at night, but Agricola sent in his cavalry and they were put to flight. The Romans responded by pushing further north. Another son was born to Agricola this year, but died before his first birthday.

In the summer of 83, Agricola faced the massed armies of the Caledonians, led by Calgacus, at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Tacitus estimates their numbers at more than 30,000. Agricola put his auxiliaries in the front line, keeping the legions in reserve, and relied on close-quarters fighting to make the Caledonians' unpointed slashing swords useless as they were unable to swing them properly or utilise thrusting attacks. Even though the Caledonians were put to rout and therefore lost this battle, two thirds of their army managed to escape and hide in the Highlands or the "trackless wilds" as Tacitus calls them. Battle casualties were estimated by Tacitus to be about 10,000 on the Caledonian side and 360 on the Roman side.

A number of authors have reckoned the battle to have occurred in the Grampian Mounth within sight of the North Sea. In particular, Roy, Surenne, Watt, Hogan and others have advanced notions that the site of the battle may have been Kempstone Hill, Megray Hill or other knolls near the Raedykes Roman camp; these points of high ground are proximate to the Elsick Mounth, an ancient trackway used by Romans and Caledonians for military manoeuvres. However, following the discovery of the Roman camp at Durno in 1975, most scholars now believe that the battle took place on the ground around Bennachie in Aberdeenshire.

Satisfied with his victory, Agricola extracted hostages from the Caledonian tribes. He may have marched his army to the northern coast of Britain, as evidenced by the probable discovery of a Roman fort at Cawdor (near Inverness).

He also instructed the prefect of the fleet to sail around the north coast, confirming (allegedly for the first time) that Britain was in fact an island.

Findings

In 2019, GUARD Archaeology team led by Iraia Arabaolaza uncovered a marching camp dating to the 1st century AD in Ayr, used by Roman legions during the invasion of Roman General Agricola. According to Arabaolaza, the fire pits were split 30 meters apart into two parallel lines. The findings also included clay-domed ovens and 26 fire pits dated to between 77- 86 AD and 90 AD loaded with burnt material and charcoal contents. Archaeologists suggested that this site had been chosen as a strategic location for the Roman conquest of Ayrshire.

Later years

Agricola was recalled from Britain in 85, after an unusually long tenure as governor. Tacitus claims Domitian ordered his recall because Agricola's successes outshone the emperor's own modest victories in Germany. He re-entered Rome unobtrusively, reporting as ordered to the palace at night.

The relationship between Agricola and the emperor is unclear; on the one hand, Agricola was awarded triumphal decorations and a statue (the highest military honours apart from an actual triumph); on the other, Agricola never again held a civil or military post, in spite of his experience and renown. He was offered the governorship of the province of Africa, but declined it, whether due to ill health or (as Tacitus claims) the machinations of Domitian.

In 93, Agricola died on his family estates in Gallia Narbonensis aged fifty-three. Rumours circulated attributing the death to a poison administered by the emperor Domitian, but no positive evidence for this was ever produced.

Today; Agricola is considered as the Conqueror of Britain

Agricola's campaigns.

The new governor was Agricola, returning to Britain, and made famous through the highly laudatory biography of him written by his son-in-law, Tacitus. Arriving in mid-78, Agricola completed the conquest of Wales in defeating the Ordovices who had destroyed a cavalry ala of Roman auxiliaries stationed in their territory. Knowing the terrain from his prior military service in Britain, he was able to move quickly to subdue them. He then invaded Anglesey, forcing the inhabitants to sue for peace.

The following year he moved against the Brigantes of northern England and the Selgovae along the southern coast of Scotland, using overwhelming military power to establish Roman control.

Agricola in Caledonia

Tacitus says that after a combination of force and diplomacy quieted discontent among the Britons who had been conquered previously, Agricola built forts in their territories in 79. In 80, he marched to the Firth of Tay (some historians hold that he stopped along the Firth of Forth in that year), not returning south until 81, at which time he consolidated his gains in the new lands that he had conquered, and in the rebellious lands that he had re-conquered. In 82, he sailed to either Kintyre or the shores of Argyll, or to both. In 83 and 84, he moved north along Scotland's eastern and northern coasts using both land and naval forces, campaigning successfully against the inhabitants and winning a significant victory over the northern British peoples led by Calgacus at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Archaeology has shown the Romans built military camps in the north along Gask Ridge, controlling the glens that provided access to and from the Scottish Highlands, and also throughout the Scottish Lowlands in northeastern Scotland.

Agricola built a network of military roads and forts to secure the Roman occupation. Existing forts were strengthened and new ones planted in northeastern Scotland along the Highland Line, consolidating control of the glens that provided access to and from the Scottish Highlands. The line of military communication and supply along southeastern Scotland and northeastern England (i.e., Dere Street) was well-fortified. In southernmost Caledonia, the lands of the Selgovae (approximating to modern Dumfriesshire and the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright) were heavily planted with forts, not only establishing effective control there, but also completing a military enclosure of south-central Scotland (most of the Southern Uplands, Teviotdale, and western Tweeddale). In contrast to Roman actions against the Selgovae, the territories of the Novantae, Damnonii, and Votadini were not planted with forts, and there is nothing to indicate that the Romans were at war with them. Agricola was recalled to Rome in 84.

Archaeology

In 2019 a marching camp dating to the 1st century AD, used by Roman legions during the invasion of Agricola. Clay-domed ovens and 26 fire pits dated to AD 77 90 were found loaded with burn and charcoal contents. The fire pits were 30 metres (98 feet) apart in two parallel lines. Archaeologists suggested that this site had been chosen as a strategic location for the Roman conquest of Ayrshire.

The conquest of Wales lasted until c. AD 77. Roman general Gnaeus Julius Agricola conquered much of northern Britain during the following seven years. In AD 84, Agricola defeated a Caledonian army, led by Calgacus, at the Battle of Mons Graupius. However, the Romans soon withdrew from northern Britain. After Hadrian's Wall was established as the northern border, tribes in the region repeatedly rebelled against Roman rule and forts continued to be maintained across northern Britain to protect against these attacks.

AD 84 117

Roman military organisation in the north c. 84 AD

Agricola's successors are not named in any surviving source, but it seems they were unable or unwilling to further subdue the far north. The fortress at Inchtuthil was dismantled before its completion and the other fortifications of the Gask Ridge in Perthshire, erected to consolidate the Roman presence in Scotland in the aftermath of Mons Graupius, were abandoned within the space of a few years. It is equally likely that the costs of a drawn-out war outweighed any economic or political benefit and it was more profitable to leave the Caledonians alone and only under de jure submission.

With the decline of imperial ambitions in Scotland (and Ireland) by AD 87 (the withdrawal of the 20th legion), consolidation based on the line of the Stanegate road (between Carlisle and Corbridge) was settled upon. Carlisle was the seat of a centurio regionarius (or district commissioner). When the Stanegate became the new frontier it was augmented by large forts as at Vindolanda and additional forts at half-day marching intervals were built at Newbrough, Magnis (Carvoran) and Brampton Old Church.

The period from 87 to 117 was used for consolidation and only a few sites north of the Stanegate line were maintained, while the signs are that an orderly withdrawal to the Solway-Tyne line was made.: 56

Modifications to the Stanegate line, with the reduction in the size of the forts and the addition of fortlets and watchtowers between them, seem to have taken place from the mid-90s onwards: 58 Apart from the Stanegate line, other forts existed along the Solway Coast at Beckfoot, Maryport, Burrow Walls (near the present town of Workington) and Moresby (near Whitehaven). Other forts in the region were built to consolidate Roman presence (Beckfoot for example may date from the late 1st century). A fort at Troutbeck may have been established from the period of Emperor Trajan (r. 98 117) onwards. Other forts that may have been established during this period include Ambleside (Galava), positioned to take advantage of ship-borne supply to the forts of the Lake District. From here, a road was constructed during the Trajanic period to Hardknott Roman Fort. A road between Ambleside to Old Penrith and/or Brougham, going over High Street, may also date from this period.

From AD 117

Scotland during the Roman Empire

Levels of Romanisation by area and date

Under Hadrian (r. 117 138), Roman occupation was withdrawn to a defensible frontier in the River Tyne-Solway Firth frontier area by the construction of Hadrian's Wall from around 122.

Hadrian - Hadrian In AD43 did not conquer Britain. By the time Hadrian became emperor in AD 117, Britain had already been under Roman control for several decades. The Roman conquest of Britain began in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius.

Hadrian is perhaps best known in Britain for commissioning the construction of Hadrian's Wall, a massive fortification in the north of the province (modern-day northern England) built around AD 122. The wall marked the northern boundary of the Roman Empire in Britain and was intended to control movements between Roman Britain and the lands to the north, inhabited by tribes like the Picts.

Hadrian s approach to ruling the empire emphasized consolidation and defense rather than expansion, which is why his reign is often remembered for fortifications like Hadrian's Wall.

When Antoninus Pius rose to the throne, he moved quickly to reverse the empire limit system put in place by his predecessor. Following his defeat of the Brigantes in 139 AD, Quintus Lollius Urbicus, the Roman Governor of Britannia, was ordered by Antoninus Pius to march north of Hadrian's Wall to conquer the Caledonian Lowlands which were settled by the Otadini, Selgovae, Damnonii and the Novantae, and to push the frontier further north. Lollius Urbicus moved three legions into position initially establishing his supply routes from Coria and Bremenium and moved three legions, the Legio II Augusta from Caerleon, the Legio VI Victrix from Eboracum, and the Legio XX Valeria Victrix from Deva Victrix into the theatre between 139 and 140 AD, and thereafter moved his army, a force of at least 16,500 men, north of Hadrian's Wall.

The Selgovae, having settled in the regions of present-day Kirkcudbrightshire and Dumfriesshire immediately northwest of Hadrian's Wall, were amongst the first of the Caledonian tribes to face Lollius Urbicus's legions together with the Otadini. The Romans, who were well versed in warfare on hilly terrain since their founding, moved quickly to occupy strategic points and high ground, some of which had already been fortified by the Caledonians with hill forts. One such was Burnswark Hill which was strategically located commanding the western route north further into Caledonia and where significant evidence of the battle has been found.

By 142 the Romans had occupied the entire area and had successfully moved the frontier north to the River Clyde-River Forth area when the Antonine Wall was constructed. This was abandoned in 162 and only subsequently re-occupied on an occasional basis. Meanwhile, the Romans retreated to the earlier and stronger Hadrian's Wall.

Roman troops penetrated far into the north of modern Scotland several more times. There is a greater density of Roman marching camps in Scotland than anywhere else in Europe as a result of at least four major attempts to subdue the area.

3rd and 4th centuries

The brief Roman invasion of Caledonia (208 211)

The most notable later expedition was in 209 when the emperor Septimius Severus, claiming to be provoked by the belligerence of the Maeatae tribe, campaigned against the Caledonian Confederacy, a coalition of Brittonic Pictish tribes of the north of Britain. He used the three legions of the British garrison (augmented by the recently formed 2nd Parthica legion), 9000 imperial guards with cavalry support, and numerous auxiliaries supplied from the sea by the British fleet, the Rhine fleet and two fleets transferred from the Danube for the purpose. According to Dio Cassius, he inflicted genocidal depredations on the natives and incurred the loss of 50,000 of his own men to the attrition of guerrilla tactics before having to withdraw to Hadrian's Wall. He repaired and reinforced the wall with a degree of thoroughness that led most subsequent Roman authors to attribute the construction of the wall to him. During the negotiations to purchase the truce necessary to secure the Roman retreat to the wall, Septimius Severus's wife, Julia Domna, criticised the sexual morals of the Caledonian women; the wife of Argentocoxos, a Caledonian chief, replied: "We consort openly with the best of men while you allow yourselves to be debauched in private by the worst". This is the first recorded utterance confidently attributable to a native of the area now known as Scotland. The emperor Septimius Severus died at York while planning to renew hostilities, and these plans were abandoned by his son Caracalla.

Emperor Constantius came to Britain in 306, despite his poor health, with an army aiming to invade northern Britain, after the provincial defences had been rebuilt following the Carausian Revolt. Little is known of his campaigns with scant archaeological evidence, but fragmentary historical sources suggest he reached the far north of Britain and won a major battle in early summer before returning south. His son Constantine (later Constantine the Great) spent a year in northern Britain at his father's side, campaigning against the Picts beyond Hadrian's Wall in the summer and autumn.

Later excursions into Scotland by the Romans were generally limited to the scouting expeditions of exploratory in the buffer zone that developed between the walls, trading contacts, bribes to purchase truces from the natives, and eventually the spread of Christianity. The degree to which the Romans interacted with the Goidelic-speaking island of Hibernia (modern Ireland) is still unresolved amongst archaeologists in Ireland.

.

Governor Of Britain - Arriving in midsummer of 77, Agricola discovered that the Ordovices of north Wales had virtually destroyed the Roman cavalry stationed in their territory. He immediately moved against them and defeated them. His campaign then moved onto Anglesey where he subjugated the entire island. Almost two decades earlier, Governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus had attempted the same but Roman forces had to withdraw in 60 CE because of the outbreak of the Boudican rebellion.

The conquest of Wales lasted until c. AD 77. Roman general Gnaeus Julius Agricola conquered much of northern Britain during the following seven years. In AD 84, Agricola defeated a Caledonian army, led by Calgacus, at the Battle of Mons Graupius. However, the Romans soon withdrew from northern Britain. After Hadrian's Wall was established as the northern border, tribes in the region repeatedly rebelled against Roman rule and forts continued to be maintained across northern Britain to protect against these attacks.

Agricola also expanded Roman rule north into Caledonia (modern Scotland). In the summer of 79, he pushed his armies to the estuary of the river Taus, usually interpreted as the Firth of Tay, virtually unchallenged, and established some forts. Though their location is left unspecified, the close dating of the fort at Elginhaugh in Midlothian makes it a possible candidate. He established himself as a good administrator by reforming the widely corrupt corn levy as well as through his military successes. He introduced Romanising measures, encouraging communities to build towns on the Roman model and gave a Roman education to sons of native nobility; albeit, as Tacitus notes, for the cynical reason of pacifying the aggressive tribes in Britannia for the servitude of Rome.

Hibernia

In 81, Agricola "crossed in the first ship" and defeated peoples unknown to the Romans until then. Tacitus, in Chapter 24 of Agricola, does not tell us what body of water he crossed. Modern scholarship favours either the Firth of Clyde or Firth of Forth. Tacitus also mentions Hibernia, so southwest Scotland is perhaps to be preferred. The text of the Agricola has been amended here to record the Romans "crossing into trackless wastes", referring to the wilds of the Galloway peninsula. Agricola fortified the coast facing Ireland, and Tacitus recalls that his father-in-law often claimed the island could be conquered with a single legion and auxiliaries. He had given refuge to an exiled Irish king whom he hoped he might use as the excuse for conquest. This conquest never happened, but some historians believe the crossing referred to was in fact a small-scale exploratory or punitive expedition to Ireland, though no Roman camps have been identified to confirm such a suggestion.

Irish legend provides a striking parallel. Tuathal Teachtmhar, a legendary High King, is said to have been exiled from Ireland as a boy, and to have returned from Britain at the head of an army to claim the throne. The traditional date of his return is between 76 and 80, and archaeology has found Roman or Romano-British artefacts in several sites associated with Tuathal

The following year, Agricola raised a fleet and encircled the tribes beyond the Forth, and the Caledonians rose in great numbers against him. They attacked the camp of the Legio IX Hispana at night, but Agricola sent in his cavalry and they were put to flight. The Romans responded by pushing further north. Another son was born to Agricola this year, but died before his first birthday.

In the summer of 83, Agricola faced the massed armies of the Caledonians, led by Calgacus, at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Tacitus estimates their numbers at more than 30,000. Agricola put his auxiliaries in the front line, keeping the legions in reserve, and relied on close-quarters fighting to make the Caledonians' unpointed slashing swords useless as they were unable to swing them properly or utilise thrusting attacks. Even though the Caledonians were put to rout and therefore lost this battle, two thirds of their army managed to escape and hide in the Highlands or the "trackless wilds" as Tacitus calls them. Battle casualties were estimated by Tacitus to be about 10,000 on the Caledonian side and 360 on the Roman side.

A number of authors have reckoned the battle to have occurred in the Grampian Mounth within sight of the North Sea. In particular, Roy, Surenne, Watt, Hogan and others have advanced notions that the site of the battle may have been Kempstone Hill, Megray Hill or other knolls near the Raedykes Roman camp; these points of high ground are proximate to the Elsick Mounth, an ancient trackway used by Romans and Caledonians for military manoeuvres. However, following the discovery of the Roman camp at Durno in 1975, most scholars now believe that the battle took place on the ground around Bennachie in Aberdeenshire.

Satisfied with his victory, Agricola extracted hostages from the Caledonian tribes. He may have marched his army to the northern coast of Britain, as evidenced by the probable discovery of a Roman fort at Cawdor (near Inverness).

He also instructed the prefect of the fleet to sail around the north coast, confirming (allegedly for the first time) that Britain was in fact an island.

Findings

In 2019, GUARD Archaeology team led by Iraia Arabaolaza uncovered a marching camp dating to the 1st century AD in Ayr, used by Roman legions during the invasion of Roman General Agricola. According to Arabaolaza, the fire pits were split 30 meters apart into two parallel lines. The findings also included clay-domed ovens and 26 fire pits dated to between 77- 86 AD and 90 AD loaded with burnt material and charcoal contents. Archaeologists suggested that this site had been chosen as a strategic location for the Roman conquest of Ayrshire.

Later years

Agricola was recalled from Britain in 85, after an unusually long tenure as governor. Tacitus claims Domitian ordered his recall because Agricola's successes outshone the emperor's own modest victories in Germany. He re-entered Rome unobtrusively, reporting as ordered to the palace at night.

The relationship between Agricola and the emperor is unclear; on the one hand, Agricola was awarded triumphal decorations and a statue (the highest military honours apart from an actual triumph); on the other, Agricola never again held a civil or military post, in spite of his experience and renown. He was offered the governorship of the province of Africa, but declined it, whether due to ill health or (as Tacitus claims) the machinations of Domitian.

In 93, Agricola died on his family estates in Gallia Narbonensis aged fifty-three. Rumours circulated attributing the death to a poison administered by the emperor Domitian, but no positive evidence for this was ever produced.

Today; Agricola is considered as the Conqueror of Britain

Gnaeus Julius Agricola

YES!

is considered to have concuored Britain

YES!

is considered to have concuored Britain

Some notes Courtesy Wiki

Gnaeus Julius Agricola was a Roman statesman and Roman Italo-Gallic general. As governor of Britain, conquered large areas of northern England, Scotland and Wales.