Everything For The Metal Detectorist - Finds MENU

Powered By Sispro1

Refresher for the Beginner and Professional

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

Pages

Member NCMD

The Normans Menu

Sterling Coins

Norman Swords

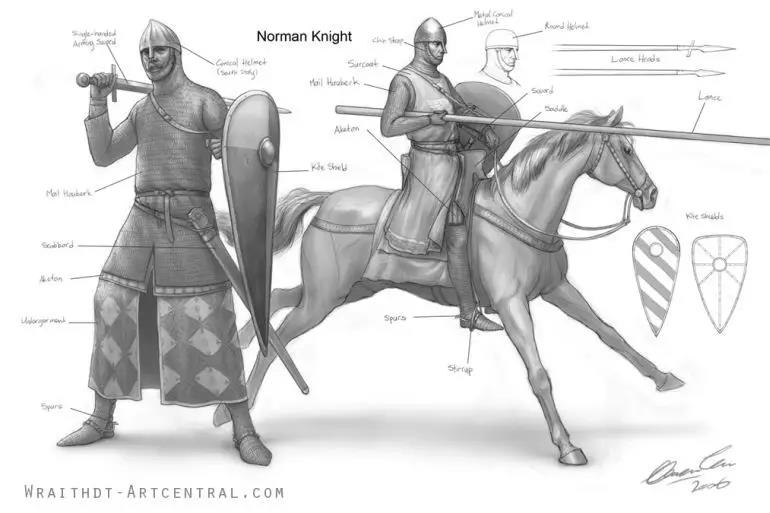

Weapons - Norman (examples) Swords

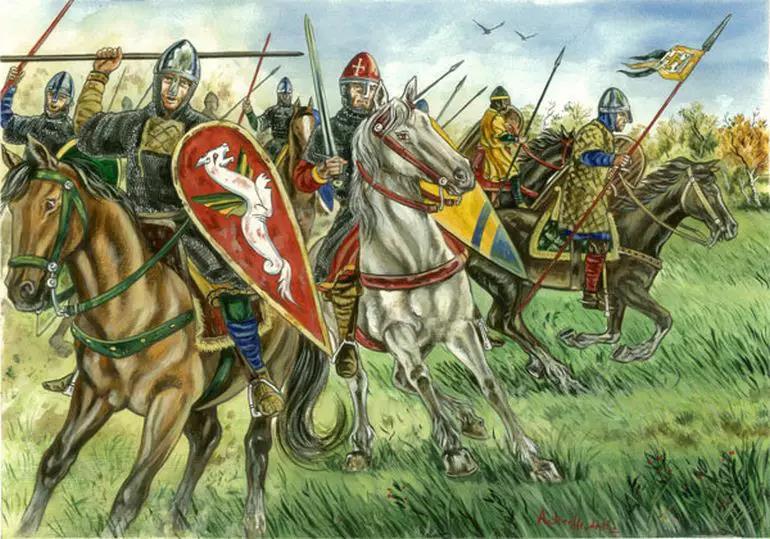

6. The Tactic Of Couched Lance

Curtesy: ArtCentral

As we mentioned at the beginning of the post, the martial scope that differentiated the medieval Norman knights (and their European counterparts) from the ordinary soldiers was directly related to the momentous charge they could mount on a battlefield. And the Norman penchant for fast and brutal warfare was rather fueled by the tactical development and adoption of the couched lance (circa late 11th century AD), which was gripped firmly between the upper arm and the chest.

This allowed the knight to mount a forceful charge through the ranks of enemy infantry (who were often loosely formed), with the heavy lance epitomizing the momentum of the heavily armored cavalryman in his full motion. And as can be surmised from this description, the infantrymen (especially the lesser trained ones) also had to deal with the devastating psychological impact of an imposing band of war-horses and their expert riders in their full panoply and armament, riding towards them in their greatest speed and momentum.

This tactical ambit of the medieval battlefield may seem simple and brutal, as aptly described by Anna Comnena, a Byzantine princess (and historian) who effusively spoke of how the knights of the First Crusade could punch through the walls of Babylon with their devastating charge. However when it came to organizing massed charges, much had to do with the discipline and training imparted in each of the Norman knights participating in the maneuver.

For example, before mounting a charge, the group of heavy horsemen was assembled in numbers of 25 to 50, known as the conrois. The conrois kept its formation very tight, so much so that it was said that even an apple could not pass through the gaps between the horses. Initially, the knights also kept their lances upright and their horses on a trot, so as not to loosen the formation. And only on the final yards were the horses made to gallop (and lances put forward), thereby preserving their strength and initiative for the momentum of impact.

Now when it came to practicality, some historians are still not sure if the same ‘charging’ tactic (and its psychological impact) could be mounted against the war-hardened infantry forces with tighter formations and better nerves. But without the doubt, the couched lance posture in itself was complemented (possibly in the later years) by innovations such as a higher-set war saddle with the protective pommel, a cantle for the hip, and a breast strap for absorbing the shock.

7. Weakness Against Arrows - Interestingly enough, our popular notion presents the scenario where the armored knight was the undisputed master of the battlefield in medieval Europe from the 12th-14th century. But historically only a part of this scope was true. In that regard, while the Norman knights were without a doubt the game-changer on the actual battlefield, they had their fair share of weaknesses. One of the primary ones among them had to with the projectiles aimed at the knights. Horses were especially vulnerable to the enemy arrows since most of them were unarmored. On top of that, the impact of the arrows on the horseman in his full momentum could pose significant challenges, with few well-placed volleys even leading to the dismounting of the knight from his horse.

The Crusaders learned it the hard way when faced with the incredible mobility of Turkic horse-archers in the battlefields of Levant and Anatolia. As a result, the predominately Norman knights of the Principality of Antioch relied more on coordination between their different contingents and troops-types, to counter the agile foes. One of such maneuvers entailed the partnership system between the heavy cavalry, infantry, and crossbowmen, who planned and progressed together to keep the mounted enemies at bay.

With the passage of time and influence from Eastern armies, the Normans (and their Crusader brethren) also adopted the tactics of ambushing, maintaining a reserve body of knights for counter-flanking, and occasional retreating (behind a solid wall of infantry). And as the maneuvers became more complex, the Norman knights practiced the habit of repeated charging and harassing in smaller groups, as opposed to a grandiosely conceived single massed charge.

This allowed the knight to mount a forceful charge through the ranks of enemy infantry (who were often loosely formed), with the heavy lance epitomizing the momentum of the heavily armored cavalryman in his full motion. And as can be surmised from this description, the infantrymen (especially the lesser trained ones) also had to deal with the devastating psychological impact of an imposing band of war-horses and their expert riders in their full panoply and armament, riding towards them in their greatest speed and momentum.

This tactical ambit of the medieval battlefield may seem simple and brutal, as aptly described by Anna Comnena, a Byzantine princess (and historian) who effusively spoke of how the knights of the First Crusade could punch through the walls of Babylon with their devastating charge. However when it came to organizing massed charges, much had to do with the discipline and training imparted in each of the Norman knights participating in the maneuver.

For example, before mounting a charge, the group of heavy horsemen was assembled in numbers of 25 to 50, known as the conrois. The conrois kept its formation very tight, so much so that it was said that even an apple could not pass through the gaps between the horses. Initially, the knights also kept their lances upright and their horses on a trot, so as not to loosen the formation. And only on the final yards were the horses made to gallop (and lances put forward), thereby preserving their strength and initiative for the momentum of impact.

Now when it came to practicality, some historians are still not sure if the same ‘charging’ tactic (and its psychological impact) could be mounted against the war-hardened infantry forces with tighter formations and better nerves. But without the doubt, the couched lance posture in itself was complemented (possibly in the later years) by innovations such as a higher-set war saddle with the protective pommel, a cantle for the hip, and a breast strap for absorbing the shock.

7. Weakness Against Arrows - Interestingly enough, our popular notion presents the scenario where the armored knight was the undisputed master of the battlefield in medieval Europe from the 12th-14th century. But historically only a part of this scope was true. In that regard, while the Norman knights were without a doubt the game-changer on the actual battlefield, they had their fair share of weaknesses. One of the primary ones among them had to with the projectiles aimed at the knights. Horses were especially vulnerable to the enemy arrows since most of them were unarmored. On top of that, the impact of the arrows on the horseman in his full momentum could pose significant challenges, with few well-placed volleys even leading to the dismounting of the knight from his horse.

The Crusaders learned it the hard way when faced with the incredible mobility of Turkic horse-archers in the battlefields of Levant and Anatolia. As a result, the predominately Norman knights of the Principality of Antioch relied more on coordination between their different contingents and troops-types, to counter the agile foes. One of such maneuvers entailed the partnership system between the heavy cavalry, infantry, and crossbowmen, who planned and progressed together to keep the mounted enemies at bay.

With the passage of time and influence from Eastern armies, the Normans (and their Crusader brethren) also adopted the tactics of ambushing, maintaining a reserve body of knights for counter-flanking, and occasional retreating (behind a solid wall of infantry). And as the maneuvers became more complex, the Norman knights practiced the habit of repeated charging and harassing in smaller groups, as opposed to a grandiosely conceived single massed charge.

8. The Feigned Flight - Unlike many of the contemporary European elite societies, the Norman knights were not averse to adopting the tactical advantages of other cultures. One of such examples might have related to the use of feigned flight in the midst of battles, probably inspired by the 9th century Bretons. Now while ‘knightly’ culture and its values of chivalry detested retreat (if even feigned) from the battlefield, the Norman formations entailing a smaller group of horsemen (conrois) were suited to such flexible ruses. In essence, the feigned flight was made to lure out the enemy soldiers (mostly their horsemen), which in effect disturbed the opposing tight formations of knights or heavy infantry, thus providing the initiative to strike for the Norman side.

And while the notion of luring out the enemy forces might seem straightforward, in practical circumstances, the stratagem required intense levels of training and coordination among the Norman knight conrois participating in the maneuver. Furthermore, the sight of flight (of the knights), even if used as a gimmick, could have demoralized the common soldiers of the army. So such tactical gambits were possibly decided before the commencement of the battle, by keeping various modes of communication open for most of the commanders on the Norman side.

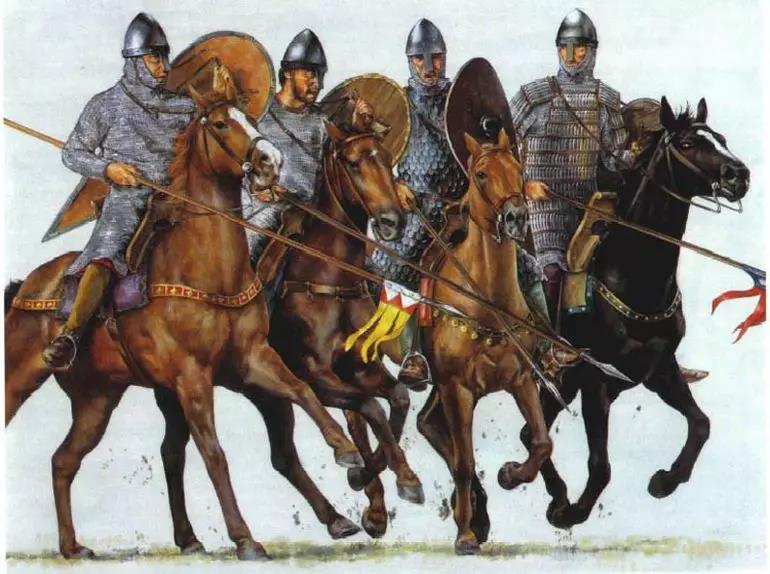

9. The Different Norman Knights

9. The Different Norman Knights

Courtesy: Scout.com

As we fleetingly mentioned in one of the earlier entries, the Norman knights didn’t really pertain to a particular group of soldiers with uniform bearing. Once again mirroring the societal values of medieval Western Europe, the knights of Norman origin were found in different walks of the military, spread across various estates, fiefs, and even kingdoms. To that end, it was the eldest son who inherited the patrimony and thus continued the hereditary generations of land-holding knightly class in the feudal society. But the options were not so clear for the younger sons, who either chose a military career or went the path of monkhood.

Considering the first choice, some opted to become vassals of the great lords. They were counted

Considering the first choice, some opted to become vassals of the great lords. They were counted

Curtesy: by Christa Hook

among the household knights and given prime parcels of lands around the lord’s estates. In return, these knights held up the tradition of loyalty, one of the enduring legacies of ancient cultures such as the Celts and Germanic tribes. Others took the more ‘diplomatic’ route of settling down and making their fortune, by marrying potentially rich heiresses. A few even went on to make their fortune through tournaments.

But arguably the most important group of Norman knights, at least from the historical perspective, were the soldiers of fortune who took upon themselves to carve their own kingdoms, in the regions of Italy, Sicily, and even upper Levant. Interestingly enough, in the initial years of 11th century AD, a major percentage of the Normans arriving in Sicily were actually employed as mercenaries by the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

10. Culture And Christianity -

But arguably the most important group of Norman knights, at least from the historical perspective, were the soldiers of fortune who took upon themselves to carve their own kingdoms, in the regions of Italy, Sicily, and even upper Levant. Interestingly enough, in the initial years of 11th century AD, a major percentage of the Normans arriving in Sicily were actually employed as mercenaries by the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

10. Culture And Christianity -

In most of medieval Europe, the elite status of Norman knights, along with their association with ‘higher’ martial pursuits, made them the crème de la crème of military endeavors, especially when it came to expansionist feats. And strengthened by the ideals of Gens Normannorum (an indigenous sense of identity and even destiny), many of the Normans did display their set of distinct cultural attributes. Some of these were intrinsically ‘Norman’, as their penchant for adaptability and military resourcefulness, while some were clearly inspired by other cultures, like the notions of chivalry and romanticism borrowed from southern France.

Intriguingly enough, the Normans, with their very name being derived from the Latin Nortmanni – denoting the Northmen (or Norsemen) raiders from Scandinavia, were descendants of the Vikings who settled in the north-western French province of Neustria (later termed as Normandy, after the Normans). But in a twist of history, in spite of their pagan heritage, future generations of Norman knights turned out to be the ‘sword arm’ of Christianity, with their conquests and influence reaching the far-flung corners of Europe and even the Levant.

Interestingly, the Normans also established a long-standing yet transparent relationship with the Papacy, as is evident from William the Conqueror’s alliance with the Vatican. In that regard, many of the ecclesiastical leaders of the church came from the Norman aristocracy, while secular Norman lords quite freely founded medieval monasteries in their realms. Many of these ‘church lands’ owed military service to their Norman overlords and as such resource-rich abbeys probably funded the first knights.

Intriguingly enough, the Normans, with their very name being derived from the Latin Nortmanni – denoting the Northmen (or Norsemen) raiders from Scandinavia, were descendants of the Vikings who settled in the north-western French province of Neustria (later termed as Normandy, after the Normans). But in a twist of history, in spite of their pagan heritage, future generations of Norman knights turned out to be the ‘sword arm’ of Christianity, with their conquests and influence reaching the far-flung corners of Europe and even the Levant.

Interestingly, the Normans also established a long-standing yet transparent relationship with the Papacy, as is evident from William the Conqueror’s alliance with the Vatican. In that regard, many of the ecclesiastical leaders of the church came from the Norman aristocracy, while secular Norman lords quite freely founded medieval monasteries in their realms. Many of these ‘church lands’ owed military service to their Norman overlords and as such resource-rich abbeys probably funded the first knights.

Courtesy Dattatreya Mandal

Sources: Spartacus-Educational / Albion-Swords / Regia Anglorum - Realm of History November 23, 2016 /reprint 27.02.20

Book References: The Normans in Sicily: The Normans in the South 1016-1130 and the Kingdom in the Sun 1130-1194 (By John Julius Norwich) / The Normans (By David Nicolle) / Norman Knight 950-1204 AD (By Christopher Gravett) / Anglo-Norman Warfare: Studies in Late Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Military (By Matthew Strickland)

Book References: The Normans in Sicily: The Normans in the South 1016-1130 and the Kingdom in the Sun 1130-1194 (By John Julius Norwich) / The Normans (By David Nicolle) / Norman Knight 950-1204 AD (By Christopher Gravett) / Anglo-Norman Warfare: Studies in Late Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Military (By Matthew Strickland)

Swords

[1]