Everything For The Metal Detectorist - Finds MENU

Powered By Sispro1

Refresher for the Beginner and Professional

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

Pages

Member NCMD

The Normans Menu

Sterling Coins

Norman Swords

The one-handed sword of the high medieval period was typically used with a shield or buckler. In the late medieval period, when the longsword came to predominate, the single-handed sword was retained as a common sidearm, especially of the estoc type, and came to be referred to as an "arming sword"

1.

During the Pre-Norman Period, the swords in use throughout Europe were of the Scandinavian type, and may be divided into three classes:

(1) those having the character of a broadsword, with parallel sharp edges and an acute point, and the tang only for a grip; (2) a similar variety having a cross guard; and (3) a sword with the blade slightly curved.

From the Norman Conquest till the end of the 12th Century, the grip of the swords was usually of wood, covered with skin, but sometimes of bone. The cross-guards began in a simple projection, but increased as time went on; together with the pommel, they were at times highly ornamented, inlaid with precious stones. The sheaths were usually of leather, stiffened with a wood framing. The blade of the swords of this period was always two-edged, and about forty inches in length; the quillons were generally straight, in other cases curved towards the blade, as in the Great Seal of King Henry II; the grip varied perhaps more than any other part, being at times almost double handed. The shape of the pommel takes many forms: round, hemispherical, square, lozenge, trefoiled or cinquefoiled.

The swords of the 13th Century resembled those of the preceding epoch. The blade was straight, broad, double-edged, and pointed. The type is well shown in the Second Seal of King Henry III. The cross-piece was usually curved towards the blade. Sometimes the curved guard threw out a kind of cusp in the middle. The crossbar was at other times straight. A variety of the straight guard forms also a cusp over the centre of the blade.

The pommel of the Medieval swords takes many forms: the round, the trefoil, the cinquefoil, the rosette, the lozenge, the conical, the pear-shaped, the square, and the fleur-de-lis, as in the Seal of King Edward I. The round pommel is either plain or ornamented on its sides: in the latter case the ornament is usually a cross, or a shield of arms. The plain round pommel is generally wheel-formed; that is, it has a projection in the centre something like the nave of a wheel. The sacred symbol of the Cross is very frequently found on the circular pommel.

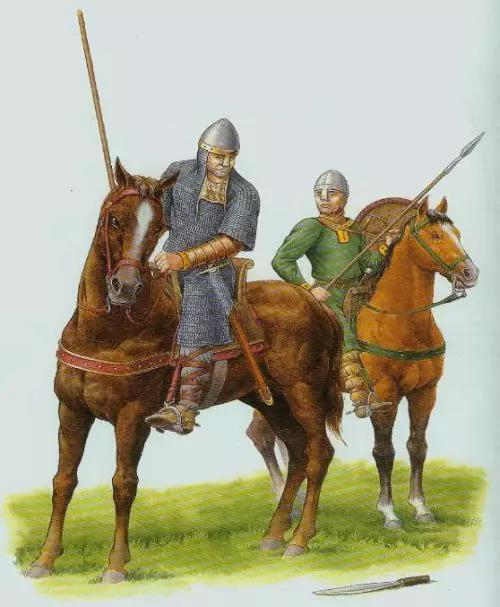

The resplendent image of a medieval knight in shining armor is even a trope of popular culture. But beyond visual magnificence and social elitism, the foremost historical factor that can be associated with a knight obviously relates to his martial prowess on the battlefield. This ambit of ardor, mobility, and even ruthlessness was kick-started by none other than the Normans, who initially hailed from Normandy, but carried forth their Viking legacy, and carved up a plethora of kingdoms and political entities in distant parts of Europe and even the Levant. So without further ado, let us take a gander at the ten incredible things you should know about the Norman knights.

1. The Lance - In one of our previous articles about the medieval knights, we talked about the importance of swords, both from the symbolic perspective (given how the cross-guard and the grip together resembled the cruciform) and its association as an instrument of status (a cultural factor that was possibly adopted from the ancient Celts and Germanic tribes). However, the weapon that truly transformed the knights (especially the Norman knights) into a battlefield force to be reckoned with, pertains to the lance.

But what exactly is a lance, especially in its historical context? In simple terms, from the 10th to 11th century, the lance wielded by a Norman knight generally comprised a straightforward stout spear, with its plain ash shaft fitted with a leaf-shaped iron-head and pretty long socket. In essence, the weapon form (in the early middle ages) harked backed to the kontos-type spear used by the heavy cavalry of the ancient times and late antiquity, like the famed Companions (Hetairoi) of Alexander and the renowned Savaran cataphracts of Persia.

Now intriguingly enough, the Bayeux Tapestry shows how many of the Norman knights held their lance overhead, which might be interpreted as a stabbing action. However in few cases, the spear is shown as being thrown mid-air, thus suggesting the use of some lance-like weapons (or short spears) as javelins from the horse-back (though the view can be disputed). In any case, the status of the lance as a knight s weapon was mirrored by the ones fitted with tailed pennons that often carried forth the heraldry or symbols associated with the carrier, like the raven standards depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry.

(1) those having the character of a broadsword, with parallel sharp edges and an acute point, and the tang only for a grip; (2) a similar variety having a cross guard; and (3) a sword with the blade slightly curved.

From the Norman Conquest till the end of the 12th Century, the grip of the swords was usually of wood, covered with skin, but sometimes of bone. The cross-guards began in a simple projection, but increased as time went on; together with the pommel, they were at times highly ornamented, inlaid with precious stones. The sheaths were usually of leather, stiffened with a wood framing. The blade of the swords of this period was always two-edged, and about forty inches in length; the quillons were generally straight, in other cases curved towards the blade, as in the Great Seal of King Henry II; the grip varied perhaps more than any other part, being at times almost double handed. The shape of the pommel takes many forms: round, hemispherical, square, lozenge, trefoiled or cinquefoiled.

The swords of the 13th Century resembled those of the preceding epoch. The blade was straight, broad, double-edged, and pointed. The type is well shown in the Second Seal of King Henry III. The cross-piece was usually curved towards the blade. Sometimes the curved guard threw out a kind of cusp in the middle. The crossbar was at other times straight. A variety of the straight guard forms also a cusp over the centre of the blade.

The pommel of the Medieval swords takes many forms: the round, the trefoil, the cinquefoil, the rosette, the lozenge, the conical, the pear-shaped, the square, and the fleur-de-lis, as in the Seal of King Edward I. The round pommel is either plain or ornamented on its sides: in the latter case the ornament is usually a cross, or a shield of arms. The plain round pommel is generally wheel-formed; that is, it has a projection in the centre something like the nave of a wheel. The sacred symbol of the Cross is very frequently found on the circular pommel.

The resplendent image of a medieval knight in shining armor is even a trope of popular culture. But beyond visual magnificence and social elitism, the foremost historical factor that can be associated with a knight obviously relates to his martial prowess on the battlefield. This ambit of ardor, mobility, and even ruthlessness was kick-started by none other than the Normans, who initially hailed from Normandy, but carried forth their Viking legacy, and carved up a plethora of kingdoms and political entities in distant parts of Europe and even the Levant. So without further ado, let us take a gander at the ten incredible things you should know about the Norman knights.

1. The Lance - In one of our previous articles about the medieval knights, we talked about the importance of swords, both from the symbolic perspective (given how the cross-guard and the grip together resembled the cruciform) and its association as an instrument of status (a cultural factor that was possibly adopted from the ancient Celts and Germanic tribes). However, the weapon that truly transformed the knights (especially the Norman knights) into a battlefield force to be reckoned with, pertains to the lance.

But what exactly is a lance, especially in its historical context? In simple terms, from the 10th to 11th century, the lance wielded by a Norman knight generally comprised a straightforward stout spear, with its plain ash shaft fitted with a leaf-shaped iron-head and pretty long socket. In essence, the weapon form (in the early middle ages) harked backed to the kontos-type spear used by the heavy cavalry of the ancient times and late antiquity, like the famed Companions (Hetairoi) of Alexander and the renowned Savaran cataphracts of Persia.

Now intriguingly enough, the Bayeux Tapestry shows how many of the Norman knights held their lance overhead, which might be interpreted as a stabbing action. However in few cases, the spear is shown as being thrown mid-air, thus suggesting the use of some lance-like weapons (or short spears) as javelins from the horse-back (though the view can be disputed). In any case, the status of the lance as a knight s weapon was mirrored by the ones fitted with tailed pennons that often carried forth the heraldry or symbols associated with the carrier, like the raven standards depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry.

2. The Weight Of Squires - Now while our popular notion suggests that squires were essentially knights in training, and thus by virtue were of noble birth, historicity states that the Norman knights also employed a large number of young men of ‘non-noble’ origins as their attendants. As a matter of fact, many of these ‘squires’ were actually paid in money, though the sum was offered quite irregularly. In any case, the job of a medieval squire was quite unenviable, with his foremost duty requiring him to carry the heavy burden of his master (knight), including the luggage and hefty weapons.

Mounted Knight gear, Siege of Jerusalem (1244 AD). Credit: Thom Atkinson

He did this with an aid of a pack-horse or rouncy and led the mighty destrier warhorse of his master through the routes.

During times of campaign, the squire was charged with setting up the tent of the knight. At times he also had to set forth at a moment’s notice for foraging and locating water holes that would sate the logistical requirements of the heavily armed and noble horsemen. And as many of the pop-cultural aficionados would know, the squires (of noble birth) were also burdened with the duty of dressing up the knights in their panoply before the commencement of a battle.

And since we brought the scope of a battle, in spite of his position as a helper of a knight, the squire was expected to actively take part in military encounters, especially when the knight was dismounted and thus needed his reserved war-horse in the midst of the fray. Moreover at times, few of the noble squires even put forth their claims to join the fight in protracted siege battles, thus mirroring a bloody rite of passage pertaining to their future knighthood.

During times of campaign, the squire was charged with setting up the tent of the knight. At times he also had to set forth at a moment’s notice for foraging and locating water holes that would sate the logistical requirements of the heavily armed and noble horsemen. And as many of the pop-cultural aficionados would know, the squires (of noble birth) were also burdened with the duty of dressing up the knights in their panoply before the commencement of a battle.

And since we brought the scope of a battle, in spite of his position as a helper of a knight, the squire was expected to actively take part in military encounters, especially when the knight was dismounted and thus needed his reserved war-horse in the midst of the fray. Moreover at times, few of the noble squires even put forth their claims to join the fight in protracted siege battles, thus mirroring a bloody rite of passage pertaining to their future knighthood.

3. The ‘Slap’ And Knights-Errant - Like most of their European counterparts, the Norman knights were basically ‘chosen’ based on their lineage, and thus the 8-10-year-old boys (puers) were sent to a lord’s household to taking their training in combat and (most importantly) following orders. Beyond the age of 14, many teenagers were inducted into the ranks of the squires. And finally, by the age of 21, they were dubbed as knights – with a seemingly odd initiation rite where the young man was given a hefty blow about the ears. He had to take on the blow without retaliating, thus symbolically suggesting that it was the only physical blow after knighthood that he was going to willingly endure.

These unmarried youths (known as juvenis) were the renowned knights-errant of numerous medieval songs and poems, who supposedly followed the rigors of chivalry to seek fame, fortunes and noble wives. In practical terms, many of the young men were retained as household knights, while the others plied their trade as mercenaries. Many of the younger sons, who had little chance of inheriting their predecessor’s properties, tried their best to marry the rich heiresses whose patrimonies they can lay claim to.

Additionally, by the 11th century, the young Norman knights took part in tournaments that entailed free-form exercises (like the French melee) in open fields. These ‘encounters’ almost played out like actual gruesome battles, with opposing team of knights fighting against each other in their full panoply while being armed with sharp weapons. The defeated knights, as a rule, had to forfeit their warhorse and rich armor, thus providing an incentive for many a cash-strapped knight errant of the period, in spite of the imminent physical danger.

These unmarried youths (known as juvenis) were the renowned knights-errant of numerous medieval songs and poems, who supposedly followed the rigors of chivalry to seek fame, fortunes and noble wives. In practical terms, many of the young men were retained as household knights, while the others plied their trade as mercenaries. Many of the younger sons, who had little chance of inheriting their predecessor’s properties, tried their best to marry the rich heiresses whose patrimonies they can lay claim to.

Additionally, by the 11th century, the young Norman knights took part in tournaments that entailed free-form exercises (like the French melee) in open fields. These ‘encounters’ almost played out like actual gruesome battles, with opposing team of knights fighting against each other in their full panoply while being armed with sharp weapons. The defeated knights, as a rule, had to forfeit their warhorse and rich armor, thus providing an incentive for many a cash-strapped knight errant of the period, in spite of the imminent physical danger.

4. Training Since Puberty - While the puers were possibly inducted into a lord’s household by the age of 10, a knight’s real combat training only started after the age of 12 or 13. One of the first exercises the that the child teenager was taught entailed riding a horse, thus mirroring the contemporary remark (paraphrased by eminent French historian Marc Bloch) – ‘he who has stayed at school till the age of twelve, and never ridden a horse, is fit only to be a priest’. To that end, it was no easy task to maintain control over the imposing and mulish stallions, especially when maneuvering had to be done with a shield in the left hand and a thrusting weapon (like a lance) in the right. Now when riding the war-horse, the left hand was obviously used to hold the rein; but during the heat of the combat, the shield had to be kept still, and hence the rein was often laid on the horse’s neck, which suggests a delicate balancing act on the part of the rider.

Via Crystal Cave Chronicles

And while the shield was an important part of Norman’s knight panoply, it was the lance and its momentum that made these heavy horsemen truly effective on the battlefield (especially with the posture of couched lance). However, at times, the sheer impact of the lance and its consequent shock could even dismount the knight-in-training from the horse-back. Suffice it to say, many practice runs resulted in serious injuries and even rare fatalities among the trainees. So over time, training was more focused on the ‘optimized’ gripping of the lance that allowed the rider to stay on the horse after a successful charge.

In that regard, 14th-century manuscripts depict particular constructs of wooden horses with wheels. The trainee was mounted atop the construct, while his companions would pull the horse at full speed, hurling the rider towards a shield pinned along with a post. The trainee had to aim for that shield with his lance, and the wooden horse was continued to be dragged even after the impact was made, thus preparing the knight to brace (with the help of his legs) after the momentum shock.

Other training methods involved practicing swords cuts and parries, often with the help of wooden posts. And interestingly, harking back to the ancient Romans, many of the blunt weapons used for training were often of double weight, thereby increasing the stamina and fortitude of the trainees, which in turn compensated for their heavy gear in actual battle scenarios.

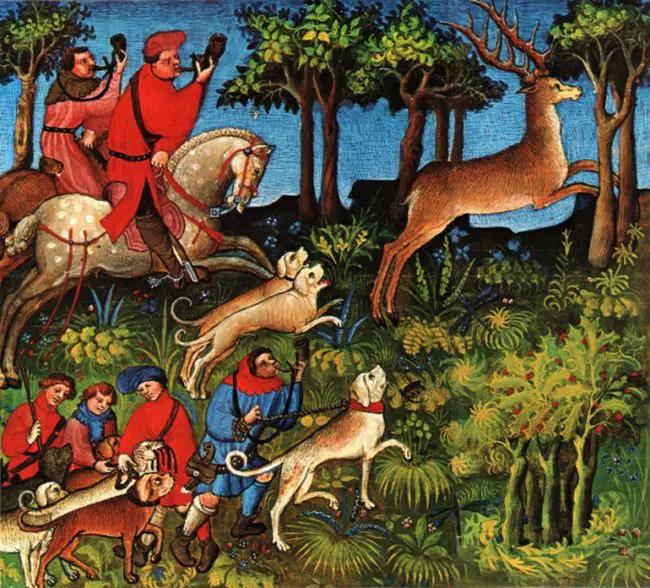

5. The Dangerous Hunts-

In that regard, 14th-century manuscripts depict particular constructs of wooden horses with wheels. The trainee was mounted atop the construct, while his companions would pull the horse at full speed, hurling the rider towards a shield pinned along with a post. The trainee had to aim for that shield with his lance, and the wooden horse was continued to be dragged even after the impact was made, thus preparing the knight to brace (with the help of his legs) after the momentum shock.

Other training methods involved practicing swords cuts and parries, often with the help of wooden posts. And interestingly, harking back to the ancient Romans, many of the blunt weapons used for training were often of double weight, thereby increasing the stamina and fortitude of the trainees, which in turn compensated for their heavy gear in actual battle scenarios.

5. The Dangerous Hunts-

Courtesy: Wikimedia Common

The martial ambit of medieval Norman culture, partly inherited due to their Viking origins, was not just limited to the rigorous (and often brutal) training fields. Much like the near-contemporary Mongols, the Norman military took particular pride in their hunting skills. The primal side of this scope was obviously related to gathering food. But as for the elite sections of the Norman society, including the knights, hunting provided them with the opportunity to practice their horsemanship and endurance, especially on the rough terrains of the countryside.

And on rare occasions, hunting was also the way one could showcase his courage and martial skill when the prey tended to be dangerous like wild boar, stag or even brown bear. To that end, Richard of Normandy, the second son of William the Conqueror, was possibly killed by a stag while hunting in the New Forest, a tract of heath-land and woods that was proclaimed as a royal forest by William himself. Interestingly enough, by the later years, many of the Norman knights even practiced their archery skills on the quicker prey – as the bow was raised to being a prestigious weapon after the Norman conquest of England.

And on rare occasions, hunting was also the way one could showcase his courage and martial skill when the prey tended to be dangerous like wild boar, stag or even brown bear. To that end, Richard of Normandy, the second son of William the Conqueror, was possibly killed by a stag while hunting in the New Forest, a tract of heath-land and woods that was proclaimed as a royal forest by William himself. Interestingly enough, by the later years, many of the Norman knights even practiced their archery skills on the quicker prey – as the bow was raised to being a prestigious weapon after the Norman conquest of England.

continued....

Weapons - Norman (examples) Swords

Swords

[1]

[2]