Famous Meteorite

Cold Bokkeveld Meteorite

Innisfree Meteorite

Ensisheim Meteorite

Hoba Meteorite

Ivuna Meteorite

A carbonaceous chondrite that fell in many pieces (the largest recovered weighing 3 kg) near the Cold Bokkeveld Mountains, in Cape Province, South Africa, on Oct. 13, 1838. From a sample of it, Friedrich Wöhler extracted an oil "with a strong bituminous odor." Having also extracted organic material from the Kaba meteorite, he concluded that these substances had a biological origin. Only later was it realized that carbon compounds could be created in space by inorganic processes. In 1951-52, G. Mueller at University College, London, found chemicals resembling hydrocarbons in the Cold Bokkeveld stone, a discovery referred to by Melvin Calvin and Susan K. Vaughan in their work on the biological significance of organic matter in meteorites.

The Cold Bokkeveld meteorite is estimated to be about 4.5 billion years old, which is roughly as old the Solar System. However, it contains something older still: microscopic diamonds. When heated, these diamonds release the inert gas xenon. The mixture of xenon isotopes found in the diamonds has not been found anywhere on Earth.

Cold Bokkeveld meteorite fragment and diamond dust extracted from it. © The Natural History Museum, London

The oldest meteorite whose fall can be dated precisely. On Nov. 7, 1492, near noon, a loud explosion preceded the arrival of a 127-kg stone meteorite in a wheat field near the village of Ensisheim in the province of Alsace, France, which at the time was part of Germany. An old woodcut depicting the scene shows the fall watched by two people emerging from a forest. In fact, a young boy was the only eyewitness and he led the local populace to the field, where the meteorite lay in a hole a meter deep. After it was retrieved, the townsfolk, believing the object to be of supernatural origin, begin to chip off bits for souvenirs, until stopped by the local magistrate.

An iron meteorite (of the ataxtite group) weighing some 60,000 kg - the largest meteorite ever found. It still lies where it was found in 1920 at Hoba Farm, near Grootfontein, Namibia. Surprisingly, there is no crater, perhaps because the great chunk of metal entered our atmosphere at a long, shallow angle and was slowed down considerably by atmospheric drag.

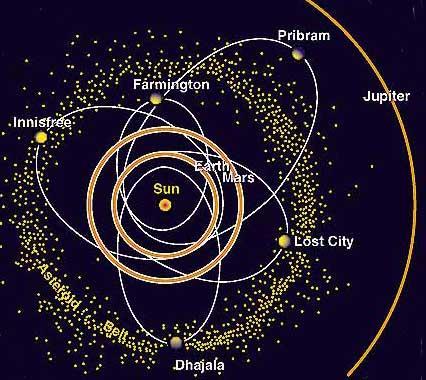

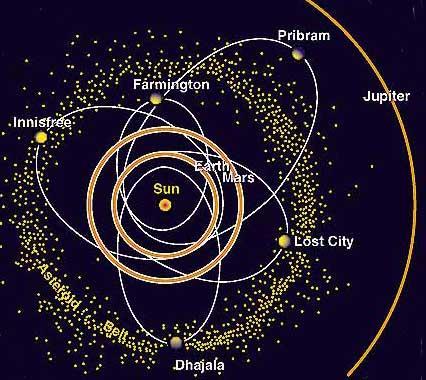

Only the third meteorite in the world whose passage through the atmosphere was recorded photographically by cameras at more than one place (the first two were the Príbram meteorite and Lost City meteorite. Such photographic evidence is important because it enables a calculation of the object's old orbit and of the area where it is likely to fall. The Innisfree meteorite fell 13 km north of the town of this name, in Alberta, Canada, at 7:17 p.m. on Feb. 5, 1977. Although an immediate search of the area, by light plane and on foot, turned up nothing, photographic records from two stations in the Meteorite Observation and Recording Program (MORP) network allowed a computer projection of the most likely fall area. Eleven days later, the largest piece of the Innisfree rock (2.07 kg) was found only a few hundred meters from the point predicted.

A 0.7-kilogram carbonaceous chondrite (type CI1, see below) which landed near Ivuna, Tanzania, on December 16, 1938. It was subsequently split into a number of samples.

Ivuna was one of four meteorites, including the Orgueil meteorite, in which Bartholomew Nagy and George Claus1 claimed to have found evidence of primitive extraterrestrial fossils. Subsequent analysis led to this claim being discredited. However, in 2001, investigation by a team from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, the Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, and the NASA

What does the classification CI1 mean?

Ivuna is one of only nine known meteorites that are classified as type CI1 carbonaceous chondrites. These meteorites contain "heavy elements" (i.e., elements other than hydrogen and helium) in nearly the same abundances as in the Sun, which means that they are essentially unaltered since they were formed at about the same time as the solar system itself, some 4.6 billion years ago. The designation CI1 indicates that Ivuna underwent a high degree of aqueous alteration (or chemical change due to the presence of water). This alteration took place in the parent body of the meteorite at low temperatures, probably in the range of 20-50°C, and in a water-rich environment. By contrast, ordinary chondrites have experienced thermal metamorphism under dry conditions in a temperature range of 600-900°C.

CI1 type meteorites are very dark, because of their high carbon content, contain a high proportion of of iron-rich clays or phyllosilicates, and have very fine grain size. In Ivuna, there is also a complete absence of chondrules, owing to the fact that they have all been altered to clays and iron oxides.

References

Claus, G., and Nagy, B. "A Microbiological Examination of Some Carbonaceous Chondrites," Nature, 192, 594 (1961).

Ehrenfreund, P., Glavin, D. P., Botta, O., Cooper, G., and Bada, J. L. "Extraterrestrial amino acids in Orgueil and Ivuna: tracing the parent body of CI type carbonaceous chondrites," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 98(5), 2138-2141 (2001).

A free template by Lucknowwebs.com for WYSIWYG WebBuilder 8

Meteor-ites

Copyright © by Nigel G Wilcox · All Rights reserved · E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Main Index

Space Cosmology

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

Science Research

*

About

Science Research

Science Theories

Desk

Site Map

BookShelf

Powered By AM3L1A

Meteor-ites

Pages:

Many of these fragments ended up in museums around the world. The remaining specimen, a rounded gray mass weighing only 55 kg and nearly without any fusion crust, can be seen today at Ensisheim resting in an elegant case in the middle of the main hall of the Regency Palace built in 1535 by the emperor Ferdinand of Austria.

Subsequently eight other fragments were found, bringing the total mass recovered to 3.79 kg. Analysis showed Innisfree to be an ordinary chondrite of the rare LL5 type.

Ames Research Center,2 showed the presence in Ivuna of two simple amino acids, glycine and beta-alanine, and linked Ivuna with a likely origin in the nucleus of a comet. For more on this discovery and its implications, see the entry for the Orgueil meteorite.

In June 2008, the largest specimen of the Ivuna meteorite was bought by the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London from a private collector in the US. Most of the other specimens are held by private collectors or by the Tanzanian government. Before being put on display, the NHM's Ivuna fragment will be taken to NASA's Johnson Space Center, where a 20g piece will be removed and subdivided into two 10g pieces. One of these pieces will be set aside, while the other will be further divided into 200mg allocations for various teams of researchers to study.

Pages within this section:

1

2

3

Sub-Menu

4

5

Meteor-ites

6

7

8

9