A Question OF British Identity - Reference

Powered By Sispro1

What Was The True Sound Of English?

By: Natalie Wolchover, Life's Little Mysteries Staff Writer

Date: 09 January 2012 Time: 01:47 PM ET

Date: 09 January 2012 Time: 01:47 PM ET

In 1776, whether you were declaring America independent from the crown or swearing your loyalty to King George III, your pronunciation would have been much the same. At that time, American and British accents hadn't yet diverged. What's surprising, though, is that Hollywood costume dramas get it all wrong: The Patriots and the Redcoats spoke with accents that were much closer to the contemporary American accent than to the Queen's English.

It is the standard British accent that has drastically changed in the past two centuries, while the typical American accent has changed only subtly.

Traditional English, whether spoken in the British Isles or the American colonies , was largely "rhotic." Rhotic speakers pronounce the "R" sound in such words as "hard" and "winter," while non-rhotic speakers do not. Today, however, non-rhotic speech is common throughout most of Britain. For example, most modern Brits would tell you it's been a "hahd wintuh."

It was around the time of the American Revolution that non-rhotic speech came into use among the upper class in southern England, in and around London. According to John Algeo in "The Cambridge History of the English Language" (Cambridge University Press, 2001), this shift occurred because people of low birth rank who had become wealthy during the Industrial Revolution were seeking ways to distinguish themselves from other commoners; they cultivated the prestigious non-rhotic pronunciation in order to demonstrate their new upper-class status .

"London pronunciation became the prerogative of a new breed of specialists orthoepists and teachers of elocution. The orthoepists decided upon correct pronunciations, compiled pronouncing dictionaries and, in private and expensive tutoring sessions, drilled enterprising citizens in fashionable articulation," Algeo wrote.

The lofty manner of speech developed by these specialists gradually became standardized it is officially called "Received Pronunciation" and it spread across Britain. However, people in the north of England, Scotland and Ireland have largely maintained their traditional rhotic accents.

Most American accents have also remained rhotic, with some exceptions: New York and Boston accents have become non-rhotic. According to Algeo, after the Revolutionary War, these cities were "under the strongest influence by the British elite."

It is the standard British accent that has drastically changed in the past two centuries, while the typical American accent has changed only subtly.

Traditional English, whether spoken in the British Isles or the American colonies , was largely "rhotic." Rhotic speakers pronounce the "R" sound in such words as "hard" and "winter," while non-rhotic speakers do not. Today, however, non-rhotic speech is common throughout most of Britain. For example, most modern Brits would tell you it's been a "hahd wintuh."

It was around the time of the American Revolution that non-rhotic speech came into use among the upper class in southern England, in and around London. According to John Algeo in "The Cambridge History of the English Language" (Cambridge University Press, 2001), this shift occurred because people of low birth rank who had become wealthy during the Industrial Revolution were seeking ways to distinguish themselves from other commoners; they cultivated the prestigious non-rhotic pronunciation in order to demonstrate their new upper-class status .

"London pronunciation became the prerogative of a new breed of specialists orthoepists and teachers of elocution. The orthoepists decided upon correct pronunciations, compiled pronouncing dictionaries and, in private and expensive tutoring sessions, drilled enterprising citizens in fashionable articulation," Algeo wrote.

The lofty manner of speech developed by these specialists gradually became standardized it is officially called "Received Pronunciation" and it spread across Britain. However, people in the north of England, Scotland and Ireland have largely maintained their traditional rhotic accents.

Most American accents have also remained rhotic, with some exceptions: New York and Boston accents have become non-rhotic. According to Algeo, after the Revolutionary War, these cities were "under the strongest influence by the British elite."

On National Identity and Language

Source: Extract From The Supplanter blogg Jan 2012

An intersting perspective from someone learning and teaching English. Taking note of the above text on early English American, American English. Please note also, this following quote:

Living overseas has eventually made me English. Before that I was British.

It has only been through increased exposure to Scots, Welsh, Northern Irish and Irish that I became English. Steadily, I ve become even more English, which, as I make my imminent return to the Olde Country, I worry may be something of a confusing experience.

Due to a combination of historical and colonial factors, and a genuine fear of racist undertones, saying that you re English has for some time been deemed a problematic way to describe your nationhood. Not so with the Scots, N.Irish or Welsh; but as I say, it is through my increased exposure overseas to people from these nations that I have eventually become comfortable in describing myself as English. Scots, Welsh, and to a lesser degree (depending upon other factors) Northern Irish, tend to eschew the British tag for themselves, and will immediately identify me as English. This is not meant usually in any kind of disparaging way, but as a means of both an identification process for themselves, which happens organically when you live away from home for a significant amount of time, and also as a means of explanation to non-native speakers of English (and also other speakers of English) confronted with all these different accents and dialects.

Source: Extract From The Supplanter blogg Jan 2012

An intersting perspective from someone learning and teaching English. Taking note of the above text on early English American, American English. Please note also, this following quote:

Living overseas has eventually made me English. Before that I was British.

It has only been through increased exposure to Scots, Welsh, Northern Irish and Irish that I became English. Steadily, I ve become even more English, which, as I make my imminent return to the Olde Country, I worry may be something of a confusing experience.

Due to a combination of historical and colonial factors, and a genuine fear of racist undertones, saying that you re English has for some time been deemed a problematic way to describe your nationhood. Not so with the Scots, N.Irish or Welsh; but as I say, it is through my increased exposure overseas to people from these nations that I have eventually become comfortable in describing myself as English. Scots, Welsh, and to a lesser degree (depending upon other factors) Northern Irish, tend to eschew the British tag for themselves, and will immediately identify me as English. This is not meant usually in any kind of disparaging way, but as a means of both an identification process for themselves, which happens organically when you live away from home for a significant amount of time, and also as a means of explanation to non-native speakers of English (and also other speakers of English) confronted with all these different accents and dialects.

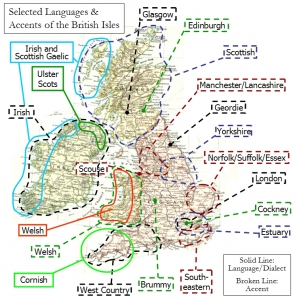

This latter aspect I have found increasingly helpful to language learners. The long and boring battle between American and British English holds no interest to me; choose one to regulate your pronunciation and be done with it, then expose yourself to other forms of spoken English to increase your knowledge. It has to be said that it s usually teachers from the UK or teachers in this case who make silly points about the superiority of one form over another. Anyway. For more advanced language learners, a whole new world of interest opens up to them when they realise that there really isn t such a thing as British English. There s a multiplicity of dialects, accents and languages from the UK; yet for most learners their only exposure is to Received Pronunciation, which about 2% of the population of UK actually use.

Teaching my students about these various dialects and accents had a dual purpose. One was to expose them to the tremendous variations in English there are in such a tiny area (the UK is about the same size as the province of China in which I currently reside, and has about half the population); the second was to encourage my students not be so overly concerned with accent and to focus upon pronunciation.

This has its origins in my surprise at just how many Chinese students would say to me how they were embarrassed about their accent, and wanted me to teach them a British accent. My surprise was initially because as I had come from Korea, where the fetishisation of the American accent holds no bounds, my British accent was very much deemed second rate (God help Aussies, Kiwis and, bless em, South Africans, teaching there). I have to admit I was a little flattered; My accent? You want to speak like me? Really? Oh, that s so Later, I realised that the same fetishisation of American accents that goes on in Korea is the same in China but for the British accent.

The off-shoot for me as a teacher and a person was further confirmation of my own Englishness. As I played the recordings of people from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, I realised something about mine and their distinct and unique cultural identities. I actually, for just about the first time in my life, felt a sort of pride in being English. Not in any superior or smug way, just in a way of an acceptance of my speech as an identifier of me and my cultural origin.

And so generally, as I mentioned above, there is this organic process of a turbo boosted national identification that occurs for all people who live overseas. Just as I have become English, I presume others have become more American or more Australian and so on. This is because both within the small expat communities it acts as locator, and within the wider community in which you live it acts as an identifier. The latter can be both irksome and beneficial. In Korea, most foreigners are assumed to be American, which acts as a double edged sword for Americans themselves (loved and loathed at the same time), and for other nationalities as a minor irritation and sometimes a good thing. For example, for English people, the universal awe in which the Premier League is held has given an undue amount of instant respect and an immediate starting point for any conversation anywhere in the world.

So I never believe people when they say they ve become less e.g. English, Irish, Welsh, or Scottish the longer they ve lived overseas. In Asia particularly, you can learn the language, know all about the history and the culture, and have lots of friends from the country you now live in, but you re always on the outside. For me, as someone who felt on the outside growing up in England, it suits me just fine, as, rather peculiarly, the distance from England has given me an opportunity to become what I never felt when I lived there.

Teaching my students about these various dialects and accents had a dual purpose. One was to expose them to the tremendous variations in English there are in such a tiny area (the UK is about the same size as the province of China in which I currently reside, and has about half the population); the second was to encourage my students not be so overly concerned with accent and to focus upon pronunciation.

This has its origins in my surprise at just how many Chinese students would say to me how they were embarrassed about their accent, and wanted me to teach them a British accent. My surprise was initially because as I had come from Korea, where the fetishisation of the American accent holds no bounds, my British accent was very much deemed second rate (God help Aussies, Kiwis and, bless em, South Africans, teaching there). I have to admit I was a little flattered; My accent? You want to speak like me? Really? Oh, that s so Later, I realised that the same fetishisation of American accents that goes on in Korea is the same in China but for the British accent.

The off-shoot for me as a teacher and a person was further confirmation of my own Englishness. As I played the recordings of people from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, I realised something about mine and their distinct and unique cultural identities. I actually, for just about the first time in my life, felt a sort of pride in being English. Not in any superior or smug way, just in a way of an acceptance of my speech as an identifier of me and my cultural origin.

And so generally, as I mentioned above, there is this organic process of a turbo boosted national identification that occurs for all people who live overseas. Just as I have become English, I presume others have become more American or more Australian and so on. This is because both within the small expat communities it acts as locator, and within the wider community in which you live it acts as an identifier. The latter can be both irksome and beneficial. In Korea, most foreigners are assumed to be American, which acts as a double edged sword for Americans themselves (loved and loathed at the same time), and for other nationalities as a minor irritation and sometimes a good thing. For example, for English people, the universal awe in which the Premier League is held has given an undue amount of instant respect and an immediate starting point for any conversation anywhere in the world.

So I never believe people when they say they ve become less e.g. English, Irish, Welsh, or Scottish the longer they ve lived overseas. In Asia particularly, you can learn the language, know all about the history and the culture, and have lots of friends from the country you now live in, but you re always on the outside. For me, as someone who felt on the outside growing up in England, it suits me just fine, as, rather peculiarly, the distance from England has given me an opportunity to become what I never felt when I lived there.

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Complimentary Topics

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

Pages

Wars of Written Language >>>

Member NCMD

Reference Menu