A Question OF Human Identity - Reference

Powered By Sispro1

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Complimentary Topics

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

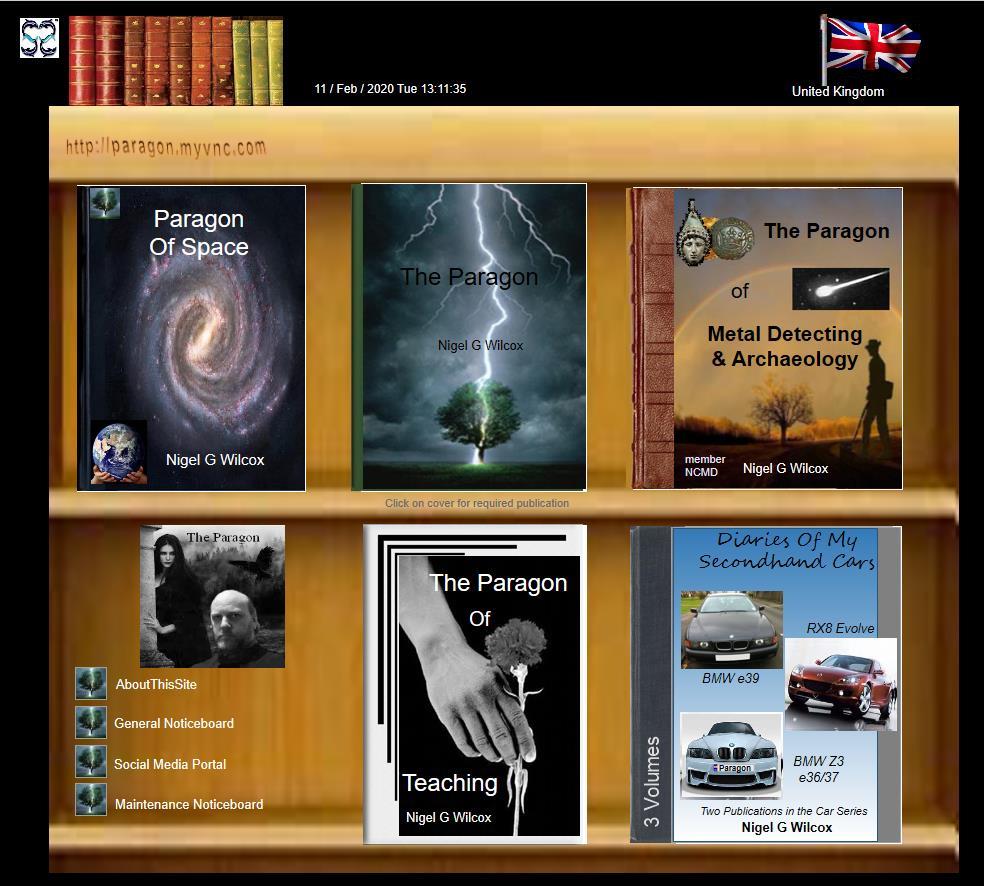

The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

Pages

Check out the Space Publication in the pseudo science section - Forbidden Archaeology - Introduction to The Denisovans and the views of Sitchen to the origins of 'Modern Man'.

Neanderthals tend to be cast as the low-browed thugs of the prehistoric world, who stood little chance against the superior intellect and hunting prowess of our own ancestors. This may be a case of unfair stereotyping, though. Neanderthals had bigger brains than us, they made jewellery, buried their dead in ancient ceremonies and used pigments – possibly for tribal markings.

It is true, however, that the Neanderthals went into a steep decline around 40,000 years ago, at a time when Homo sapiens from Africa were settling in Eurasia. Perhaps they were struggling to compete for resources, were killed in conflicts or were simply less well adapted to changes in climate that led our own ancestors to move north and east.

There’s a postscript to this story. While the Neanderthals died out as a species, in one sense they are still around today. Interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals means that all non-Africans alive today carry about 1-5% Neanderthal DNA. Everyone has acquired slightly different parts of the Neanderthal genome and so collectively there is a substantial fraction (at least 20%) of the Neanderthal genome spread through the living human population.

Wait ... we interbred with another species?

Yes, genetics shows that the ancestors of everyone outside of Africa interbred with Neanderthals, probably more than once. There was also interbreeding with another archaic group called the Denisovans. We don’t know much about what these other ancient cousins looked like as their fossils are so fragmented. But from a finger bone found in a cave in Siberia, scientists were able to extract high quality DNA belonging to a Denisovan girl who lived about 41,000 years ago.

Intriguingly, Denisovan DNA shows up only in modern day Indigenous Australians and Papua New Guineans, suggesting that their ancestors must have met the Denisovans on their way across the globe, probably somewhere in south-east Asia.

We can only speculate on the circumstances of these interbreeding events and whether they were peaceful mergers of different tribes or violent encounters.

Could we use cloning to bring our extinct cousins back to life?

Theoretically, it would be possible to cut and paste Neanderthal or Denisovan mutations into a modern human genome, and then transfer that into an egg and grow a baby using a surrogate mother. In his book Regenesis: How Synthetic Biology Will Reinvent Nature and Ourselves, Harvard geneticist George Church speculates about the possibility of using genetic engineering to resurrect extinct creatures. “If society becomes comfortable with cloning and sees value in true human diversity, then the whole Neanderthal creature itself could be cloned by a surrogate mother chimp – or by an extremely adventurous female human,” Church wrote.

In a less ethically fraught version of this experiment, scientists at several labs are currently growing Neanderthalised cells and even organoids – miniature brains and livers – to better understand how Neanderthal biology differed from our own.

When did we learn to speak?

This is tricky, as language leaves no direct trace on the fossil record and even today’s neuroscientists haven’t fully figured out how the human brain produces language. Some argue that primitive versions of language pre-date Homo sapiens, based on early evidence of collective hunting and other sophisticated behaviours.

For instance, Boxgrove Man, a 500,000 year old Homo heidelbergensis fossil (another extinct relative), was found alongside the remains of now extinct species of rhinoceros, bears and voles, which had signs of having been butchered.

The so-called language gene FOXP2, known to be crucial for speech, also holds clues. The Homo sapiens version of this gene has mutations that are not seen in chimps or other animals. We now know that Neanderthals shared these same mutations.

However, modern humans have double the number of mutations in FOXP2’s flanking DNA that determines when the gene is switched on and off, hinting that we could have evolved a qualitatively different capacity for language than our relatives.

What next?

Human evolution is not over, but it’s impossible to predict how we’re going to turn out. It’s tempting to assume that we are on an ever-upward intellectual trajectory, but there’s no guarantee of this. In fact, the human brain has become about 5-10% smaller during the past 20,000 years. Perhaps this is comparable to the pattern seen in domestic animals, which almost always have smaller brains than their wild counterparts.

“Maybe we’ve domesticated ourselves and those bits of the brain that our ancestors needed aren’t so important any more,” says Stringer.

It’s also possible that we are swapping individual brainpower for collective forms of intelligence. “Our brains are energetically very expensive – they use about 20% of our energy,” says Stringer. “So if evolution can get away with a smaller brain it will.”

Courtesy: The Guardian, Hannah Devlin Science correspondent - msn.com 13.02.18

It is true, however, that the Neanderthals went into a steep decline around 40,000 years ago, at a time when Homo sapiens from Africa were settling in Eurasia. Perhaps they were struggling to compete for resources, were killed in conflicts or were simply less well adapted to changes in climate that led our own ancestors to move north and east.

There’s a postscript to this story. While the Neanderthals died out as a species, in one sense they are still around today. Interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals means that all non-Africans alive today carry about 1-5% Neanderthal DNA. Everyone has acquired slightly different parts of the Neanderthal genome and so collectively there is a substantial fraction (at least 20%) of the Neanderthal genome spread through the living human population.

Wait ... we interbred with another species?

Yes, genetics shows that the ancestors of everyone outside of Africa interbred with Neanderthals, probably more than once. There was also interbreeding with another archaic group called the Denisovans. We don’t know much about what these other ancient cousins looked like as their fossils are so fragmented. But from a finger bone found in a cave in Siberia, scientists were able to extract high quality DNA belonging to a Denisovan girl who lived about 41,000 years ago.

Intriguingly, Denisovan DNA shows up only in modern day Indigenous Australians and Papua New Guineans, suggesting that their ancestors must have met the Denisovans on their way across the globe, probably somewhere in south-east Asia.

We can only speculate on the circumstances of these interbreeding events and whether they were peaceful mergers of different tribes or violent encounters.

Could we use cloning to bring our extinct cousins back to life?

Theoretically, it would be possible to cut and paste Neanderthal or Denisovan mutations into a modern human genome, and then transfer that into an egg and grow a baby using a surrogate mother. In his book Regenesis: How Synthetic Biology Will Reinvent Nature and Ourselves, Harvard geneticist George Church speculates about the possibility of using genetic engineering to resurrect extinct creatures. “If society becomes comfortable with cloning and sees value in true human diversity, then the whole Neanderthal creature itself could be cloned by a surrogate mother chimp – or by an extremely adventurous female human,” Church wrote.

In a less ethically fraught version of this experiment, scientists at several labs are currently growing Neanderthalised cells and even organoids – miniature brains and livers – to better understand how Neanderthal biology differed from our own.

When did we learn to speak?

This is tricky, as language leaves no direct trace on the fossil record and even today’s neuroscientists haven’t fully figured out how the human brain produces language. Some argue that primitive versions of language pre-date Homo sapiens, based on early evidence of collective hunting and other sophisticated behaviours.

For instance, Boxgrove Man, a 500,000 year old Homo heidelbergensis fossil (another extinct relative), was found alongside the remains of now extinct species of rhinoceros, bears and voles, which had signs of having been butchered.

The so-called language gene FOXP2, known to be crucial for speech, also holds clues. The Homo sapiens version of this gene has mutations that are not seen in chimps or other animals. We now know that Neanderthals shared these same mutations.

However, modern humans have double the number of mutations in FOXP2’s flanking DNA that determines when the gene is switched on and off, hinting that we could have evolved a qualitatively different capacity for language than our relatives.

What next?

Human evolution is not over, but it’s impossible to predict how we’re going to turn out. It’s tempting to assume that we are on an ever-upward intellectual trajectory, but there’s no guarantee of this. In fact, the human brain has become about 5-10% smaller during the past 20,000 years. Perhaps this is comparable to the pattern seen in domestic animals, which almost always have smaller brains than their wild counterparts.

“Maybe we’ve domesticated ourselves and those bits of the brain that our ancestors needed aren’t so important any more,” says Stringer.

It’s also possible that we are swapping individual brainpower for collective forms of intelligence. “Our brains are energetically very expensive – they use about 20% of our energy,” says Stringer. “So if evolution can get away with a smaller brain it will.”

Courtesy: The Guardian, Hannah Devlin Science correspondent - msn.com 13.02.18

(Early Humans pgs-7-8)

Human, Briton - Language

Member NCMD

Reference Menu