Copyright 2012 by Nigel G Wilcox All Rights reserved E-Mail: ngwilcox@gmx.co.uk

Research

Archaeology - Sumerian Tablets

Copyright 2012 by Nigel G Wilcox All Rights reserved E-Mail: ngwilcox@gmx.co.uk

Powered By Sispro1

Archaeological

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

F Archaeology Menu

Pages

Member NCMD

Sumerian Tablets: A Deeper Understanding of the Oldest Known Written Language

The Sumerian language was developed in ancient Mesopotamia and is the oldest known written language. This language was written in a script known as cuneiform, which was later adapted by other languages that emerged in Mesopotamia and its neighboring regions, including Akkadian, Elamite, and Hittite.

In the modern world, paper (and various electronic devices) is the medium on which writing is made. The Sumerians, however, did not invent paper and used a different medium for their cuneiform script. Documents and text were inscribed by the Sumerians on clay tablets, which has the advantage of greater durability than paper. One of the consequences of this is that a large number of Sumerian clay tablets have survived over the millennia and have been unearthed by archaeologists. Once the Sumerian language was deciphered, much information could be obtained from these tablets.

In the modern world, paper (and various electronic devices) is the medium on which writing is made. The Sumerians, however, did not invent paper and used a different medium for their cuneiform script. Documents and text were inscribed by the Sumerians on clay tablets, which has the advantage of greater durability than paper. One of the consequences of this is that a large number of Sumerian clay tablets have survived over the millennia and have been unearthed by archaeologists. Once the Sumerian language was deciphered, much information could be obtained from these tablets.

Courtesy - Original publication 9 May, 2019 - 22:56 dhwty - Ancient Origins, Reconstructing The History of Humanity's Past

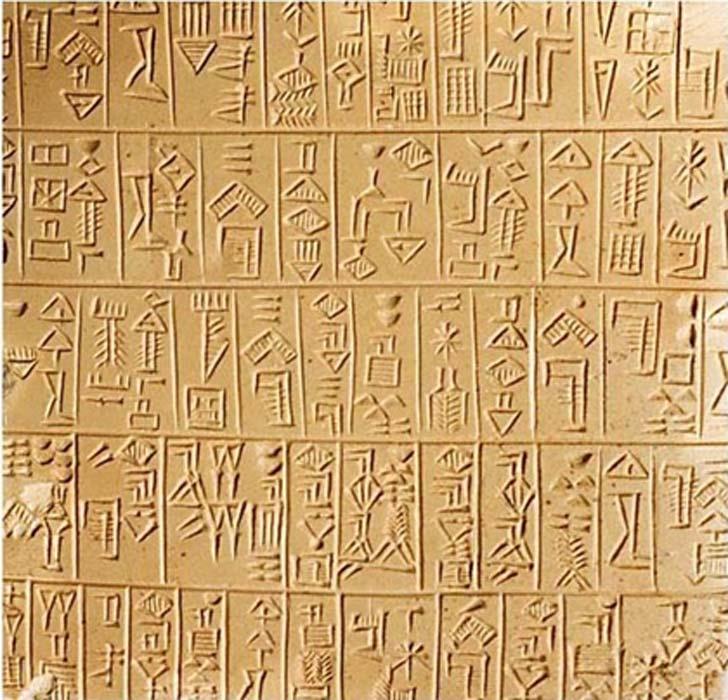

Cuneiform script of the Sumerian tablet (Juan Aunión / Adobe

The Sumerian language is considered to be a language isolate, which means that there is currently no known language related to it. This language emerged in the Sumerian civilization , which was based in southern Mesopotamia (modern day southern Iraq), and was first attested around 3100 BC. In the millennium that followed, the Sumerian civilization flourished and with it their language.

During the 24 th century BC, northern and southern Mesopotamia were unified under the Akkadians, who created the world’s first empire. The Akkadian language gradually

replaced Sumerian as a spoken language. Nevertheless, the Sumerian language continued as a written language for a much longer period of time, though its usage was greatly diminished. Written Akkadian ceased to be used around the beginning of the Christian period and Sumerian went extinct shortly before this happened.

Sumerian inscription, 6+6 columns, 120 compartments of archaic monumental cuneiform script. ( Public Domain )

What Script Is On the Sumerian Tablets?

The Sumerian script is known as cuneiform, which, incidentally, is a relatively modern term originating from the early 18 th century. This word is derived from Latin and Middle French roots and means ‘wedge-shaped’. This is an apt description of the script, as it is easily recognized thanks to its wedge-shaped characters.

Cuneiform is believed to have originated around 8000 BC and was developed for economic purposes. Initially, this script took the form of pictograms, which were used to graphically represent trade goods and livestock. Small clay tokens representing these goods were made and placed in sealed clay envelopes. In order to show the contents of the envelope, a token would be pressed onto the clay on its exterior.

The Sumerian script is known as cuneiform, which, incidentally, is a relatively modern term originating from the early 18 th century. This word is derived from Latin and Middle French roots and means ‘wedge-shaped’. This is an apt description of the script, as it is easily recognized thanks to its wedge-shaped characters.

Cuneiform is believed to have originated around 8000 BC and was developed for economic purposes. Initially, this script took the form of pictograms, which were used to graphically represent trade goods and livestock. Small clay tokens representing these goods were made and placed in sealed clay envelopes. In order to show the contents of the envelope, a token would be pressed onto the clay on its exterior.

Sumerian clay accounting tokens, replaced

by Sumerian tablets.

(Jastrow / CC BY-SA 2.5)

by Sumerian tablets.

(Jastrow / CC BY-SA 2.5)

As time went by, the Sumerians realized that they could replace the tokens by writing into the clay themselves, which would have been much easier. Over time, the symbols were stylized, simplifying the writing process and resulting in the birth of cuneiform. This connection between the clay tokens and the cuneiform script was made in the 1970s by Denise Schmandt-Besserat, a French archaeologist.

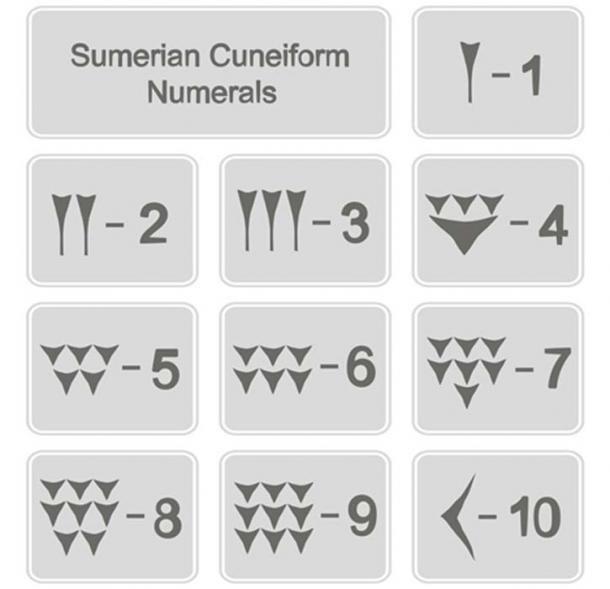

Apart from the type of trade goods, the Sumerian merchants were also interested in keeping track of their quantity and this led to the development of the numeral system in cuneiform. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, the Sumerians used clay tokens to represent the type of trade goods. These tokens represented the number of objects as well.

For instance, if 10 loaves of bread were to be recorded, 10 clay tokens of this item would be made. In order to verify that the quantity of the actual objects matched that of the tokens, one need only to count the objects and the tokens.

This technique is known as correspondence counting and was in use long before the emergence of the Sumerian civilization , though other sorts of counters, such as tally markers, were used instead. This technique was simple, and it worked, though it was cumbersome especially if a merchant had to deal with a large quantity of goods. After the development of the cuneiform script, the clay tokens were replaced with inscriptions on clay tablets, which made recording easier.

Nevertheless, having to draw the symbol for a loaf of bread 10 times to represent that amount was still not very efficient. Therefore, the Sumerians developed a numerical system, whereby quantities of goods were represented by abstract symbols, which would have further simplified the recording process.

Apart from the type of trade goods, the Sumerian merchants were also interested in keeping track of their quantity and this led to the development of the numeral system in cuneiform. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, the Sumerians used clay tokens to represent the type of trade goods. These tokens represented the number of objects as well.

For instance, if 10 loaves of bread were to be recorded, 10 clay tokens of this item would be made. In order to verify that the quantity of the actual objects matched that of the tokens, one need only to count the objects and the tokens.

This technique is known as correspondence counting and was in use long before the emergence of the Sumerian civilization , though other sorts of counters, such as tally markers, were used instead. This technique was simple, and it worked, though it was cumbersome especially if a merchant had to deal with a large quantity of goods. After the development of the cuneiform script, the clay tokens were replaced with inscriptions on clay tablets, which made recording easier.

Nevertheless, having to draw the symbol for a loaf of bread 10 times to represent that amount was still not very efficient. Therefore, the Sumerians developed a numerical system, whereby quantities of goods were represented by abstract symbols, which would have further simplified the recording process.

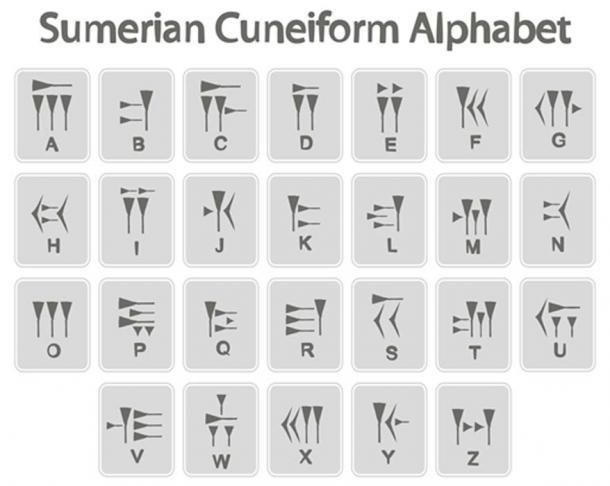

Sumerian cuneiform alphabet found on Sumerian tablets. ( drutska / Adobe)

The cuneiform script was inscribed on a variety of material, including stone, metal, and wood. The medium of choice for the Sumerians (as well as other civilizations that used this script), however, was the clay tablet. Using a stylus (commonly made of reed), a scribe would inscribe the desired characters onto a block of soft clay, which would then be sun-dried.

These tablets were fragile and could be recycled by soaking them in water and forming new tablets. Other tablets were fired in kilns (or unintentionally when a building burnt down), which made them hard and durable, thus allowing them to survive in the archaeological record, and to be discovered by archaeologists.

Where Were Sumerian Tablets Discovered?

At some sites, small amounts of clay tablets were found, whereas at others, vast repositories of this material have been unearthed. As previously mentioned, cuneiform and clay tablets were used not only by the Sumerians, but by other civilizations in Mesopotamia and the neighboring regions as well. Therefore, it follows that some of these sites contain clay tablets not of the Sumerian language, but of other languages.

In fact, considering that the Akkadian language became the lingua franca of the region following the ascent of the Akkadian Empire, there are several sites where deposits of Akkadian clay tablets have been discovered. These sites include the Library of Ashurbanipal (about 30000 clay tablets), Assur (over 16000 clay tablets), and Mari (around 25000 clay tablets).

Sites where a significant number of Sumerian clay tablets were found include Drehem and Ebla. The former is situated about 10 kilometers (3 miles) to the south of the Sumerian city of Nippur and has yielded more than 15,000 clay tablets. Whereas Ebla is located in Syria and its clay tablets, in both Sumerian and Eblaite, number in the thousands. In order to make sense of the contents of these clay tablets, it would be necessary for the Sumerian language to first be deciphered.

These tablets were fragile and could be recycled by soaking them in water and forming new tablets. Other tablets were fired in kilns (or unintentionally when a building burnt down), which made them hard and durable, thus allowing them to survive in the archaeological record, and to be discovered by archaeologists.

Where Were Sumerian Tablets Discovered?

At some sites, small amounts of clay tablets were found, whereas at others, vast repositories of this material have been unearthed. As previously mentioned, cuneiform and clay tablets were used not only by the Sumerians, but by other civilizations in Mesopotamia and the neighboring regions as well. Therefore, it follows that some of these sites contain clay tablets not of the Sumerian language, but of other languages.

In fact, considering that the Akkadian language became the lingua franca of the region following the ascent of the Akkadian Empire, there are several sites where deposits of Akkadian clay tablets have been discovered. These sites include the Library of Ashurbanipal (about 30000 clay tablets), Assur (over 16000 clay tablets), and Mari (around 25000 clay tablets).

Sites where a significant number of Sumerian clay tablets were found include Drehem and Ebla. The former is situated about 10 kilometers (3 miles) to the south of the Sumerian city of Nippur and has yielded more than 15,000 clay tablets. Whereas Ebla is located in Syria and its clay tablets, in both Sumerian and Eblaite, number in the thousands. In order to make sense of the contents of these clay tablets, it would be necessary for the Sumerian language to first be deciphered.

Ruins of Ebla, Syria, where Sumerian tablets were discovered . (siempreverde22 / Abode)

Fortunately, by the time the clay tablets were being unearthed from the two sites, i.e. the 20 th century, the Sumerian language had already been deciphered. The decipherment of cuneiform began during the early part of the 19 th century, when scholars began to tackle the monumental inscriptions left behind by the Achaemenid Empire.

The language used by this empire was Old Persian, which was written using a variance of the cuneiform script (known as Old Persian cuneiform). Once this script was deciphered, scholars realized that the Achaemenid inscriptions were in fact composed of three languages and that they all spoke of the same thing. Therefore, once Old Persian was deciphered the other two scripts could be studied as well.

It was determined that the two other languages were Elamite and Akkadian. The decipherment of the latter was an important development, as it provided a prototype for the interpretation of other languages written in cuneiform. Initially, scholars believed that Sumerian was a special way of noting Akkadian and it was only during the 20 th century that they realized their mistake and recognized Sumerian as a separate language altogether. As Sumerian is a language isolate, its structure is unrelated to any other known language, making its translation a challenge for scholars.

Nevertheless, Sumerian continued to be used by the Babylonian priesthood even after its demise as a living language. As a result, grammatical lists and vocabularies were compiled, while many literal translations of many religious texts into Babylonian were made. The text that survive provide scholars today with ample material to work with.

As mentioned earlier, the cuneiform script developed as a means to keep track of the flow of goods. This is seen, for instance, in the clay tablets from Drehem, on which such statements as “Urazagnuuna received from Nirnbati 21 sheep, 2 lambs, 36 kids, which have passed inspection.” and “The chief of the cattle market Abbagagga delivers 11 oxen, 5 sheep, 3 lambs, 10 rams, 2 kids to lntaia” are found.

The language used by this empire was Old Persian, which was written using a variance of the cuneiform script (known as Old Persian cuneiform). Once this script was deciphered, scholars realized that the Achaemenid inscriptions were in fact composed of three languages and that they all spoke of the same thing. Therefore, once Old Persian was deciphered the other two scripts could be studied as well.

It was determined that the two other languages were Elamite and Akkadian. The decipherment of the latter was an important development, as it provided a prototype for the interpretation of other languages written in cuneiform. Initially, scholars believed that Sumerian was a special way of noting Akkadian and it was only during the 20 th century that they realized their mistake and recognized Sumerian as a separate language altogether. As Sumerian is a language isolate, its structure is unrelated to any other known language, making its translation a challenge for scholars.

Nevertheless, Sumerian continued to be used by the Babylonian priesthood even after its demise as a living language. As a result, grammatical lists and vocabularies were compiled, while many literal translations of many religious texts into Babylonian were made. The text that survive provide scholars today with ample material to work with.

As mentioned earlier, the cuneiform script developed as a means to keep track of the flow of goods. This is seen, for instance, in the clay tablets from Drehem, on which such statements as “Urazagnuuna received from Nirnbati 21 sheep, 2 lambs, 36 kids, which have passed inspection.” and “The chief of the cattle market Abbagagga delivers 11 oxen, 5 sheep, 3 lambs, 10 rams, 2 kids to lntaia” are found.

This Sumerian tablet records the transfer of a piece of land. (Kaldari / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Apart from the type of transactions, the tablets also provide the date during which they were made, and scholars were able to shed some light on the Sumerian calendar . The use of the cuneiform script for accounting is also evident in Ebla, as expenses and acquisitions of the royal palace form the subject matter of the majority of tablets from the site.

Although the cuneiform script was initially developed for economic purposes, the Sumerians soon used it for other purposes as well. This is perhaps best reflected in the increasing complexity of the script over the course of time. When the cuneiform script was fully developed, it was not only able to represent objects and numbers, but a variety of linguistic elements as well.

While some characters are logograms, which represent words on their own, others are phonograms, which represent spoken syllables. There were also characters that functioned as determinatives, which indicates the category of the word. This was a complicated writing system, and scholars have identified about 1000 different characters in the older texts and 400 in the newer ones.

Although the cuneiform script was initially developed for economic purposes, the Sumerians soon used it for other purposes as well. This is perhaps best reflected in the increasing complexity of the script over the course of time. When the cuneiform script was fully developed, it was not only able to represent objects and numbers, but a variety of linguistic elements as well.

While some characters are logograms, which represent words on their own, others are phonograms, which represent spoken syllables. There were also characters that functioned as determinatives, which indicates the category of the word. This was a complicated writing system, and scholars have identified about 1000 different characters in the older texts and 400 in the newer ones.

Sumerian cuneiform numbers found on Sumerian tablets. ( drutska / Adobe)

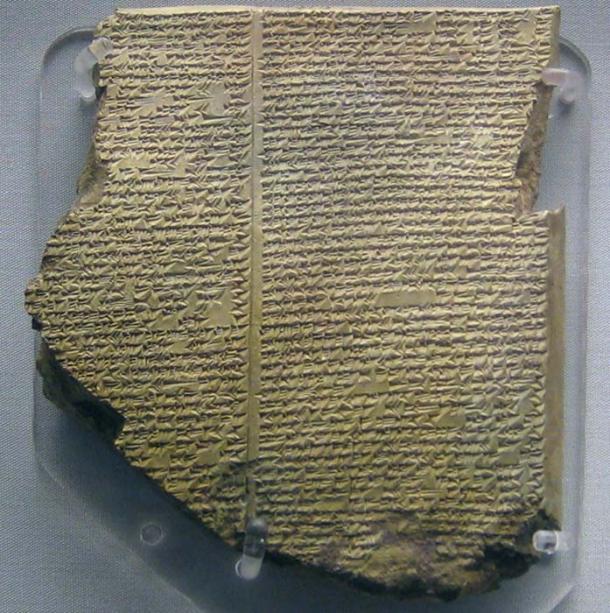

What Famous Works Are Found on Sumerian Tablets?

One well-known text recorded on Sumerian clay tablets is the Epic of Gilgamesh , considered to be the oldest work of literature in the world. The standard version of this epic was written in Akkadian, and was discovered by Hormuzd Rassam, a Turkish Assyriologist, in the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh during the middle of the 19 th century. Despite the fact that the text is incomplete, it is the fullest extant text of the epic that we have at present.

A Sumerian version of the epic also exists, though it is much less famous than its Akkadian counterpart. Moreover, it is much less complete as well, consisting of five poems, namely ‘Gilgamesh and Huwawa’, ‘Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven’, ‘Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish’, ‘Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld’, and ‘The Death of Gilgamesh’. It has been speculated that these poems circulated independently, as opposed to unified text like the one discovered at Nineveh.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is indicative of the situation between the Akkadian and Sumerian languages. Although the Sumerians invented the cuneiform and began writing on clay tablets, the records they left behind are somewhat overshadowed by those of the Akkadians. As some may already be aware, the Akkadians rose to power under Sargon of Akkad during the 24 th century BC and established the world’s first empire. From this position of dominance, the Akkadian language became a lingua franca and was used not only within the empire, but also beyond its borders. More importantly, the Akkadian gradually came to replace Sumerian as a language of communication.

One well-known text recorded on Sumerian clay tablets is the Epic of Gilgamesh , considered to be the oldest work of literature in the world. The standard version of this epic was written in Akkadian, and was discovered by Hormuzd Rassam, a Turkish Assyriologist, in the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh during the middle of the 19 th century. Despite the fact that the text is incomplete, it is the fullest extant text of the epic that we have at present.

A Sumerian version of the epic also exists, though it is much less famous than its Akkadian counterpart. Moreover, it is much less complete as well, consisting of five poems, namely ‘Gilgamesh and Huwawa’, ‘Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven’, ‘Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish’, ‘Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld’, and ‘The Death of Gilgamesh’. It has been speculated that these poems circulated independently, as opposed to unified text like the one discovered at Nineveh.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is indicative of the situation between the Akkadian and Sumerian languages. Although the Sumerians invented the cuneiform and began writing on clay tablets, the records they left behind are somewhat overshadowed by those of the Akkadians. As some may already be aware, the Akkadians rose to power under Sargon of Akkad during the 24 th century BC and established the world’s first empire. From this position of dominance, the Akkadian language became a lingua franca and was used not only within the empire, but also beyond its borders. More importantly, the Akkadian gradually came to replace Sumerian as a language of communication.

The Sumerian tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh. (BabelStone / Public Domain )

After the collapse of the Akkadian Empire, the Sumerian civilization experienced a renaissance under the Third Dynasty of Ur , though this was only for a short period of time. At the end of this Sumerian revival, Mesopotamia came under the control of the First Babylonian Empire. Like the Sumerians, the new rulers used the cuneiform script and wrote on clay tablets.

The Babylonian language, however, was not related to Sumerian but was a variant of Akkadian. The Assyrian language too is a variant of Akkadian. One of the consequences of the proliferation of Akkadian is that the quantity of clay tablets written in this language (or one of its variants) outnumbers those written in Sumerian.

Still, the clay tablets left behind by the Sumerians provide an invaluable source of information regarding this ancient civilization. From these tablets, scholars have learned not only about the workings of the Sumerian language, but also about the culture and way of life of this ancient civilization. As an example, as religious texts and myths were recorded on clay tablets we have today an understanding of the Sumerian belief system.

There are numerous clay tablets on which stories of the gods are recorded, for instance, the Sumerian Creation Myth (referred to as the Eridu Genesis by Thorkild Jacobsen) and Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld . While the former deals with the Sumerian belief of how the world was created, the latter reveals their beliefs about death and the Underworld.

There also exists what is known as the Sumerian King List , which is an intriguing stone tablet listing ancient kings of Sumer, their supposed length of reign and location of their kingdoms. It includes prehistoric rulers and claims reigns lasting thousands of years, including 8 kings which ruled for a total of 241,200 years . Most scholars dismiss these reigns as fictional inserts, with the first listed ruler whose historicity has been archaeologically verified being Enmebaragesi of Kish, around 2600 BC. These later dynastical rulers are thus seen as more plausible, although it is noted that not all known dynasties are listed.

Lastly, it may be pointed out that although Sumerian clay tablets have been found in the thousands, not all of them have been translated yet. As scholars continue to translate these tablets, more light may be shed on the Sumerians and would allow us to paint a more complete picture of this ancient civilization.

The Babylonian language, however, was not related to Sumerian but was a variant of Akkadian. The Assyrian language too is a variant of Akkadian. One of the consequences of the proliferation of Akkadian is that the quantity of clay tablets written in this language (or one of its variants) outnumbers those written in Sumerian.

Still, the clay tablets left behind by the Sumerians provide an invaluable source of information regarding this ancient civilization. From these tablets, scholars have learned not only about the workings of the Sumerian language, but also about the culture and way of life of this ancient civilization. As an example, as religious texts and myths were recorded on clay tablets we have today an understanding of the Sumerian belief system.

There are numerous clay tablets on which stories of the gods are recorded, for instance, the Sumerian Creation Myth (referred to as the Eridu Genesis by Thorkild Jacobsen) and Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld . While the former deals with the Sumerian belief of how the world was created, the latter reveals their beliefs about death and the Underworld.

There also exists what is known as the Sumerian King List , which is an intriguing stone tablet listing ancient kings of Sumer, their supposed length of reign and location of their kingdoms. It includes prehistoric rulers and claims reigns lasting thousands of years, including 8 kings which ruled for a total of 241,200 years . Most scholars dismiss these reigns as fictional inserts, with the first listed ruler whose historicity has been archaeologically verified being Enmebaragesi of Kish, around 2600 BC. These later dynastical rulers are thus seen as more plausible, although it is noted that not all known dynasties are listed.

Lastly, it may be pointed out that although Sumerian clay tablets have been found in the thousands, not all of them have been translated yet. As scholars continue to translate these tablets, more light may be shed on the Sumerians and would allow us to paint a more complete picture of this ancient civilization.

A Stray Sumerian Tablet

Zabala, southern Iraq,

ca 2200 BCE

MS Doc. 829

ca 2200 BCE

MS Doc. 829

Sumerian clay tablet (MS Doc. 829)

Zabala, southern Iraq, ca 2200 BCE

MS Doc. 829

This diminutive clay tablet was written by a Sumerian scribe in an administrative office around 2200 BC. The full translation of the laconic text runs as follows:

18 jars of pig fat - Balli.

4 jars of pig fat - Nimgir-ab-lah.

Fat dispensed (at ?) the city of Zabala.

Ab-kid-kid, the scribe.

4th year 10th month.

There are plenty of uncertainties about this translation. We cannot be sure that the personal names Balli, Ningir-ablah and Ab-kid-kid are correctly transcribed because of the multivalence of cuneiform signs at this date. Moreover, there are no verbs to tell us whether Balli and Nimgir-ablah were receiving pig fat or handing it out. The fat was either poured out at Zabala or for Zabala, an ancient city of central Sumer whose patron deity was the goddess Inana, identified with the mounds of Ibzeikh. The tablet may have been written at Zabala, but it is also possible it was written at, and was rediscovered in, the even more important city of Umma further to the east. To decide this we need to take account of other similar documents.

There are several clues in this short text which allow us to position it in an archival context, and comparison. Tablets dated by year and month (no day, and no ‘year-name’ which was the better attested practice) are known to belong late in the decades of the Dynasty of Akkad which ruled south Mesopotamia in the twenty-third and twenty-second centuries BC. While very few such ‘mu-iti’ (year-month) tablets have been recovered in archaeological excavations, plenty appeared on the antiquities market in the early decades of the twentieth century and are scattered among the museums of the western world, including the Louvre, the British Museum, Liverpool, Manchester, Edinburgh, St Petersburg, Yale and Chicago. A study of these texts was included in B. R. Foster’s work Umma in the Sargonic period (Hamden CT, 1982), especially Chapter 4. He discusses numerous tablets which record the issue of food stuffs and other commodities. He writes “animal fats were an important part of human diet”, lard “was stored in jars, and issued by the sìla [ca. 1 litre]”. … “It may also have been an important commercial product, as stocks of it were kept in various cities outside of Umma itself and records kept at Umma as to what was on hand or disbursed in those cities” (pp. 116-70).

This reads very aptly for our tablet, and that it is relevant becomes apparent when we find that one of his texts mentions Balli, another records Zabala as the place where the pig fat was used, and a third tablet concerned with pig fat mentions an Ab-kid-kid. Here he is the scribe, and Balli and Nimgir-ab-lah must be receiving, issuing, or authorizing the issue of the pig fat. While Nimgir-ablah is new to us, Balli turns up regularly in the texts discussed by Foster, and he seems to be an official in charge of a wide range of oils, from pig fat and butter to sesame oil and almond oil. It is virtually certain that this little tablet was clandestinely excavated some time early in the twentieth century, and found its way to Europe along with many other tablets from an institutional archive-a palace or conceivably also a temple. As for its more precise date, this is still sub judice, but along with the rest of its archive it probably belongs to a time when Shar-kali-sharri, the last king of the Dynasty of Akkad, had lost control of parts of the south, and documents at Umma were no longer dated by his regnal years, but by another system. Unfortunately we don’t know what the starting point for the ‘4th year’ was.

Nicholas Postgate, Trinity College.

https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/

Production: Team Digital Content Unit

Presenting: Nicholas Postgate

Research Assistant: Catherine Ansorge

Film made by: Amélie Deblauwe and Błażej Mikuła

Music: Little Planet and Relaxing - Bensound.com

Category

Education

Zabala, southern Iraq, ca 2200 BCE

MS Doc. 829

This diminutive clay tablet was written by a Sumerian scribe in an administrative office around 2200 BC. The full translation of the laconic text runs as follows:

18 jars of pig fat - Balli.

4 jars of pig fat - Nimgir-ab-lah.

Fat dispensed (at ?) the city of Zabala.

Ab-kid-kid, the scribe.

4th year 10th month.

There are plenty of uncertainties about this translation. We cannot be sure that the personal names Balli, Ningir-ablah and Ab-kid-kid are correctly transcribed because of the multivalence of cuneiform signs at this date. Moreover, there are no verbs to tell us whether Balli and Nimgir-ablah were receiving pig fat or handing it out. The fat was either poured out at Zabala or for Zabala, an ancient city of central Sumer whose patron deity was the goddess Inana, identified with the mounds of Ibzeikh. The tablet may have been written at Zabala, but it is also possible it was written at, and was rediscovered in, the even more important city of Umma further to the east. To decide this we need to take account of other similar documents.

There are several clues in this short text which allow us to position it in an archival context, and comparison. Tablets dated by year and month (no day, and no ‘year-name’ which was the better attested practice) are known to belong late in the decades of the Dynasty of Akkad which ruled south Mesopotamia in the twenty-third and twenty-second centuries BC. While very few such ‘mu-iti’ (year-month) tablets have been recovered in archaeological excavations, plenty appeared on the antiquities market in the early decades of the twentieth century and are scattered among the museums of the western world, including the Louvre, the British Museum, Liverpool, Manchester, Edinburgh, St Petersburg, Yale and Chicago. A study of these texts was included in B. R. Foster’s work Umma in the Sargonic period (Hamden CT, 1982), especially Chapter 4. He discusses numerous tablets which record the issue of food stuffs and other commodities. He writes “animal fats were an important part of human diet”, lard “was stored in jars, and issued by the sìla [ca. 1 litre]”. … “It may also have been an important commercial product, as stocks of it were kept in various cities outside of Umma itself and records kept at Umma as to what was on hand or disbursed in those cities” (pp. 116-70).

This reads very aptly for our tablet, and that it is relevant becomes apparent when we find that one of his texts mentions Balli, another records Zabala as the place where the pig fat was used, and a third tablet concerned with pig fat mentions an Ab-kid-kid. Here he is the scribe, and Balli and Nimgir-ab-lah must be receiving, issuing, or authorizing the issue of the pig fat. While Nimgir-ablah is new to us, Balli turns up regularly in the texts discussed by Foster, and he seems to be an official in charge of a wide range of oils, from pig fat and butter to sesame oil and almond oil. It is virtually certain that this little tablet was clandestinely excavated some time early in the twentieth century, and found its way to Europe along with many other tablets from an institutional archive-a palace or conceivably also a temple. As for its more precise date, this is still sub judice, but along with the rest of its archive it probably belongs to a time when Shar-kali-sharri, the last king of the Dynasty of Akkad, had lost control of parts of the south, and documents at Umma were no longer dated by his regnal years, but by another system. Unfortunately we don’t know what the starting point for the ‘4th year’ was.

Nicholas Postgate, Trinity College.

https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/

Production: Team Digital Content Unit

Presenting: Nicholas Postgate

Research Assistant: Catherine Ansorge

Film made by: Amélie Deblauwe and Błażej Mikuła

Music: Little Planet and Relaxing - Bensound.com

Category

Education

Courtesy - Original publication 9 May, 2019 - 22:56 dhwty - Ancient Origins, Reconstructing The History of Humanity's Past Sumerian Tablets

Archaeological