Copyright 2012 by Nigel G Wilcox All Rights reserved E-Mail: ngwilcox@gmx.co.uk

Wales Origins & The People - Reference

Leaders & Monarchs of Wales

Powered By Sispro1

Wales and England: AD 1066-1267

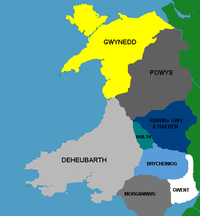

The most prolonged threat to the independent Welsh tribes begins with the arrival of the Normans in England. By this time Wales has settled down as four reasonably stable principalities. In the north is Gwynedd; south of that is Powys; in the southwest of the peninsula is Deheubarth; and in the southeast Morgannwg (or Glamorgan).

William I makes no serious attempt to conquer Wales himself, but he gives the border regions of Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford as earldoms to his feudal vassals. Armed sorties against Wales are among their responsibilities. Given such a task, the marcher lords (from 'march' meaning border) become notorious for their anarchy and violence.

Meanwhile the Welsh principalities are in almost constant warfare among themselves. From time to time a leader acquires enough power to be accepted as paramount over a broad region. One such is Rhys ap Gruffudd in the south of the country. In a series of encounters with English armies in the 1160s, he is sufficiently successful for an accomodation to be reached between himself and the English king.

On his way to Ireland in 1171 Henry II meets and acknowledges Rhys, accepting him as the lord of south Wales and as his feudal vassal. For a while such compromises bring peace to the region, until signs of weakness in the opposing side prompt the Welsh to claim greater independence or the English to attempt stricter control.

During the 13th century rulers from three successive generations of the royal family of Gwynedd unify the peninsula so effectively that they are accepted as rulers of all Wales. The first is Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. On his death, in 1240, a chronicler describes him as the prince of Wales. His son, David II, is the first man actually to claim that resonant title - in 1244. David's nephew, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, even gets the English king to acknowledge him as prince of Wales.

In 1258 Llywelyn receives the homage of all the other Welsh princes. His status is formalized in 1267 in a treaty agreed at Shrewsbury (also sometimes called the treaty of Montgomery) between himself and the English king, Henry III. Henry acknowledges Llywelyn as overlord of all the Welsh fiefs, and accepts his homage to the English throne as prince of Wales on behalf of the entire region. This is the peak of national dignity for medieval Wales. The status of the principality changes dramatically with the accession of Henry III's eldest son, Edward I. He proves himself a far more aggressive monarch than his father.

Edward I and Wales: AD 1277-1301

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, acknowledged prince of Wales by Henry III in 1267, seems almost to go out of his way to affront Henry's successor, Edward I, after his accession in 1272. He fails to attend the coronation in 1274, declines a summons to do homage, and refuses to discharge a large debt to the English king.

In 1277 Edward moves decisively against his recalcitrant vassal. Three English armies march into Wales, from Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford. Llywelyn and his forces are soon isolated in the mountainous region of Snowdon. By early November lack of food compels them to surrender.

Llywelyn is forced to sign a treaty on November 9 at Conwy. It strips him of nearly all his territories, reducing the principality to the area of Snowdon. Anglesey is allowed him on lease from the king of England, but the rest of Wales is now to be administered by English agents - a role which they fulfil with such brutality that there is a widespread uprising, headed by Llywelyn, in 1282.

Edward reacts as forcefully as before, with another invasion of Wales during which Llywelyn is killed. But this time the English king takes the whole of Wales into his own hands.

By the statute issued at Rhuddlan in 1284 the principality of Wales is transformed into counties, on the English principle, to be governed by officials on behalf of the crown.

In 1301 Edward adds the final symbolic touch to this suppression of Wales. He revives the much cherished title of 'prince of Wales', bestowing it on his heir, the future Edward II. Ironically Wales now has what it has been fighting for. It is a principality, but an English one. The title has remained, through the centuries, the highest honour granted to the eldest son and heir apparent of the English monarch.

The Welsh, predictably, are unhappy with these arrangements (a further uprising in 1294-5 is ruthlessly crushed by Edward's armies). But the king has a powerful answer.

The very year after the death of Llywelyn, Edward begins the construction of the great castles which are still the glory of the northwest coast of Wales. Each is completed within a few years. Like the clench of a stone fist, these fortresses grip the final Welsh refuge - the region of Snowdonia - from Harlech (1283-9) in the south, to Caernarfon (1283-92) and Beaumaris (1295-8) on either side of the Menai Strait, and on to Conwy (1283-8) in the north. Overawed by these strongholds, Wales remains quiet for a century - till the time of Owain Glyn Dwr.

Owain Glyn Dwr: AD 1399-1416

Richard II reigning in England from 1377 to 1399, has no son. There is therefore, during this period, no prince of Wales. But Henry IV, seizing the throne in 1399, immediately creates his son Henry prince of Wales. In the following year, 1400, the Welsh proclaim a prince of Wales of their own - Owain Glyn Dwr. It is an act of deliberate rebellion. (Glyn Dwr is also known to the Welsh as Owain ap Gruffudd, and is traditionally spelt Owen Glendower in English.)

Wales in general has supported Richard II, but Glyn Dwr has been closer to the party of Henry IV. At first he seems an unlikely leader, swept up almost accidentally in a minor rebellion.

Under Glyn Dwr's leadership the uprising grows in strength, in spite of an early defeat at Welshpool in 1400. A breakthrough in the power of the rebels comes with the capture in 1402 of Edmund Mortimer, member of an Anglo-Norman family with great estates on the Welsh borders. Mortimer is related by descent to the English throne and by marriage to the Percy family, earls of Northumberland. Glyn Dwr persuades Mortimer to change sides. Mortimer marries Glyn Dwr's daughter.

Henry IV is now confronted by a potentially fatal alliance, with Northumberland able to raise the north of England against him, and Mortimer and Glyn Dwr much of the west and Wales.

The death of the glamorous young Henry Percy ('Hotspur'), in battle at Shrewsbury in 1403, is a setback for the rebels. But in 1404 Glyn Dwr captures the important English strongholds of Aberystwyth and Harlech. He begins now to rule as the prince of Wales, establishing an administration, holding parliaments, negotiating with the pope about Welsh bishops. In 1405 an alliance is even drawn up between himself, Mortimer and Nothumberland as to how they will divide England and Wales between them.

But from that year of high hopes the tide begins to turn against Glyn Dwr, largely due to the persistent campaigning of the other prince of Wales, the future Henry V.

In 1408 Glyn Dwr loses Aberystwyth and Harlech. By 1410 he is reduced to the status of an outlaw. After 1412 no more is heard of him. He is believed to have died somewhere in hiding in about 1416.

The long-standing dream of establishing an independent Welsh principality has crumbled yet again. But ironically, before the end of the century, Wales achieves something known in modern times as a reverse takeover (in which a smaller unit takes control of a larger). Instead of a Welsh prince of Wales, there is from 1485 a Welsh king of England and Wales - in the form of Henry Tudor, or Henry VII

Towards a united kingdom: AD 1536-1800

The accession to the English throne of the Tudor dynasty, with its Welsh origins, transforms Wales from a conquered territory to an integral part of the English kingdom. The change is acknowledged in an act of parliament passed in 1536, with modifications added in 1543.

The practical purpose of these acts is to give Wales an adminstrative system, based on counties, which is compatible with that of England. It replaces the earlier feudal territories, granted to marcher lords for the purpose of subduing the hostile Welsh. Wales becomes, as a result of these changes, a principality within the English kingdom. From the Reformation onwards, its political story merges with that of England.

Welsh language and literature: from the 16th c. AD

The Reformation, with its emphasis on receiving the word of God in one's own language, brings great benefit to Wales. In the mid-16th there are fewer than 250,000 inhabitants of the principality, yet the Protestant government of Elizabeth I is persuaded to pass an act providing for a Welsh translation of the Anglican liturgy and of the Bible.

The Book of Common Prayer and the New Testament are published in Welsh in 1567. The complete Bible follows in 1588. Both provide an invaluable focus for the Welsh language - the only version of Celtic to remain a living tongue for a large community within the British isles, in an unbroken tradition surviving to the present day.

At the same period as the Reformation, the attitudes of the Renaissance have a beneficial effect on Welsh literature. The Renaissance passion for rediscovering classical texts becomes, in the Welsh context, a scholarly interest in the region's great bardic tradition of oral poetry. Important works are published in the 16th century, analyzing the grammar of the Welsh language and the rules of bardic poetry.

There are periods when the interest in these traditions slackens. And inevitably immigration and other pressures (such as the use of English in schools) gradually reduce the percentage of the population for whom Welsh is the first language.

Nevertheless the figures remain amazingly high. From a Welsh-speaking 54% of the population in 1891, the proportion reduces to 37% in 1921, 26% in 1961 and 20% in 1991. This present-day 20% amounts to about half a million people - more than have spoken Welsh at most periods in the past, and sufficient in number to be provided with radio and television in their own language.

The rediscovery of the bardic past gathers new vigour during the 19th century, answering the twin needs of Welsh nationalism and the contemporary fascination with everything medieval. Soon after Scott popularizes medieval Scotland, Charlotte Guest does something similar for Wales with her translation in 1839-49 of the Mabinogion.

The Mabinogion is a collection of eleven tales, based on the ancient oral tradition but written in prose between the 11th and 13th century for recital at the courts of Welsh princes. The tales survive in two manuscripts of the 14th-15th century, the White Book of Rhydderch and the Red Book of Hergest.

The expression of the Welsh identity through language, literature and music is seen above all in the tradition of the eisteddfod. Competitions between bards were common in the Middle Ages. The first assembly (the meaning of eisteddfod) to combine both musical and literary contests is generally considered to be a Christmas gathering held in Cardigan castle in 1176 by Rhys ap Gruffudd.

The interest in eisteddfods (or in Welsh eisteddfodau) declines during the 16th and 17th centuries but is revived in the late 18th century - spurred on by the Cymmrodorion Society, a group of homesick Welshmen living in London. Their enthusiasm leads to regional eisteddfods being held throughout Wales, followed by the decision taken, in Denbigh in 1860, to establish a national body to be known as The Eisteddfod. As a result the first official National Eisteddfod was held in Aberdare in 1861. Now an annual event, it ends each year with the chairing of the bard, the poet whose work in the traditional bardic form has won the top prize.

But the 18th century does more than revive the eisteddfod. It provides a magnficent new outlet for Welsh musical talent with the arrival of Methodism.

Methodism and the chapel choir: from the 18th century

Wales is one of the earliest centres of the evangelical revival in Britain. While the Wesley brothers are still at Oxford, a Welsh layman, Howel Harris, experiences a sudden revelation in 1735 which sends him on the road as an itinerant preacher. From 1737 he teams up with a like-minded curate, Daniel Rowlands. The two are already making a stir in Wales when the Methodist George Whitefield joins them for a few months during 1739.

Methodism, with its richly emotional appeal, suits the Welsh - though the influence of Whitefield means that they adopt the harsher Calvinist variety, emphasizing predestination (an issue on which Whitefield differs from the Wesleys).

Just as Charles Wesley provides the English Methodists with an abundance of satisfying hymns and tunes, so an early Methodist minister, William Williams, does the same for the Welsh (he is the author of more than 800 hymns).

Within this new communal tradition the all-male chapel choir becomes one of the most characteristic of Welsh institutions. The chapel itself is the centre of social and cultural life - particularly in the isolated valleys which acquire a new prosperity during the 19th century on account of their coal.

Coal and iron: 19th - 20th century AD

Wales is well equipped with raw materials for the developing Industrial Revolution. Abundant supplies are available locally to meet the new demand for iron (particularly for railway lines) and for coal (to fuel the furnaces of iron works, railway engines and steamships).

The Welsh supply of coal outlasts the iron, so from the mid-19th century new iron and steel works are established near the harbours of the south coast, round Swansea, Cardiff and Newport. Here foreign ore can be imported, while coal to fuel the furnaces can be fetched the short distance from the mining valleys which run up into the hills.

The most prolonged threat to the independent Welsh tribes begins with the arrival of the Normans in England. By this time Wales has settled down as four reasonably stable principalities. In the north is Gwynedd; south of that is Powys; in the southwest of the peninsula is Deheubarth; and in the southeast Morgannwg (or Glamorgan).

William I makes no serious attempt to conquer Wales himself, but he gives the border regions of Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford as earldoms to his feudal vassals. Armed sorties against Wales are among their responsibilities. Given such a task, the marcher lords (from 'march' meaning border) become notorious for their anarchy and violence.

Meanwhile the Welsh principalities are in almost constant warfare among themselves. From time to time a leader acquires enough power to be accepted as paramount over a broad region. One such is Rhys ap Gruffudd in the south of the country. In a series of encounters with English armies in the 1160s, he is sufficiently successful for an accomodation to be reached between himself and the English king.

On his way to Ireland in 1171 Henry II meets and acknowledges Rhys, accepting him as the lord of south Wales and as his feudal vassal. For a while such compromises bring peace to the region, until signs of weakness in the opposing side prompt the Welsh to claim greater independence or the English to attempt stricter control.

During the 13th century rulers from three successive generations of the royal family of Gwynedd unify the peninsula so effectively that they are accepted as rulers of all Wales. The first is Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. On his death, in 1240, a chronicler describes him as the prince of Wales. His son, David II, is the first man actually to claim that resonant title - in 1244. David's nephew, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, even gets the English king to acknowledge him as prince of Wales.

In 1258 Llywelyn receives the homage of all the other Welsh princes. His status is formalized in 1267 in a treaty agreed at Shrewsbury (also sometimes called the treaty of Montgomery) between himself and the English king, Henry III. Henry acknowledges Llywelyn as overlord of all the Welsh fiefs, and accepts his homage to the English throne as prince of Wales on behalf of the entire region. This is the peak of national dignity for medieval Wales. The status of the principality changes dramatically with the accession of Henry III's eldest son, Edward I. He proves himself a far more aggressive monarch than his father.

Edward I and Wales: AD 1277-1301

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, acknowledged prince of Wales by Henry III in 1267, seems almost to go out of his way to affront Henry's successor, Edward I, after his accession in 1272. He fails to attend the coronation in 1274, declines a summons to do homage, and refuses to discharge a large debt to the English king.

In 1277 Edward moves decisively against his recalcitrant vassal. Three English armies march into Wales, from Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford. Llywelyn and his forces are soon isolated in the mountainous region of Snowdon. By early November lack of food compels them to surrender.

Llywelyn is forced to sign a treaty on November 9 at Conwy. It strips him of nearly all his territories, reducing the principality to the area of Snowdon. Anglesey is allowed him on lease from the king of England, but the rest of Wales is now to be administered by English agents - a role which they fulfil with such brutality that there is a widespread uprising, headed by Llywelyn, in 1282.

Edward reacts as forcefully as before, with another invasion of Wales during which Llywelyn is killed. But this time the English king takes the whole of Wales into his own hands.

By the statute issued at Rhuddlan in 1284 the principality of Wales is transformed into counties, on the English principle, to be governed by officials on behalf of the crown.

In 1301 Edward adds the final symbolic touch to this suppression of Wales. He revives the much cherished title of 'prince of Wales', bestowing it on his heir, the future Edward II. Ironically Wales now has what it has been fighting for. It is a principality, but an English one. The title has remained, through the centuries, the highest honour granted to the eldest son and heir apparent of the English monarch.

The Welsh, predictably, are unhappy with these arrangements (a further uprising in 1294-5 is ruthlessly crushed by Edward's armies). But the king has a powerful answer.

The very year after the death of Llywelyn, Edward begins the construction of the great castles which are still the glory of the northwest coast of Wales. Each is completed within a few years. Like the clench of a stone fist, these fortresses grip the final Welsh refuge - the region of Snowdonia - from Harlech (1283-9) in the south, to Caernarfon (1283-92) and Beaumaris (1295-8) on either side of the Menai Strait, and on to Conwy (1283-8) in the north. Overawed by these strongholds, Wales remains quiet for a century - till the time of Owain Glyn Dwr.

Owain Glyn Dwr: AD 1399-1416

Richard II reigning in England from 1377 to 1399, has no son. There is therefore, during this period, no prince of Wales. But Henry IV, seizing the throne in 1399, immediately creates his son Henry prince of Wales. In the following year, 1400, the Welsh proclaim a prince of Wales of their own - Owain Glyn Dwr. It is an act of deliberate rebellion. (Glyn Dwr is also known to the Welsh as Owain ap Gruffudd, and is traditionally spelt Owen Glendower in English.)

Wales in general has supported Richard II, but Glyn Dwr has been closer to the party of Henry IV. At first he seems an unlikely leader, swept up almost accidentally in a minor rebellion.

Under Glyn Dwr's leadership the uprising grows in strength, in spite of an early defeat at Welshpool in 1400. A breakthrough in the power of the rebels comes with the capture in 1402 of Edmund Mortimer, member of an Anglo-Norman family with great estates on the Welsh borders. Mortimer is related by descent to the English throne and by marriage to the Percy family, earls of Northumberland. Glyn Dwr persuades Mortimer to change sides. Mortimer marries Glyn Dwr's daughter.

Henry IV is now confronted by a potentially fatal alliance, with Northumberland able to raise the north of England against him, and Mortimer and Glyn Dwr much of the west and Wales.

The death of the glamorous young Henry Percy ('Hotspur'), in battle at Shrewsbury in 1403, is a setback for the rebels. But in 1404 Glyn Dwr captures the important English strongholds of Aberystwyth and Harlech. He begins now to rule as the prince of Wales, establishing an administration, holding parliaments, negotiating with the pope about Welsh bishops. In 1405 an alliance is even drawn up between himself, Mortimer and Nothumberland as to how they will divide England and Wales between them.

But from that year of high hopes the tide begins to turn against Glyn Dwr, largely due to the persistent campaigning of the other prince of Wales, the future Henry V.

In 1408 Glyn Dwr loses Aberystwyth and Harlech. By 1410 he is reduced to the status of an outlaw. After 1412 no more is heard of him. He is believed to have died somewhere in hiding in about 1416.

The long-standing dream of establishing an independent Welsh principality has crumbled yet again. But ironically, before the end of the century, Wales achieves something known in modern times as a reverse takeover (in which a smaller unit takes control of a larger). Instead of a Welsh prince of Wales, there is from 1485 a Welsh king of England and Wales - in the form of Henry Tudor, or Henry VII

Towards a united kingdom: AD 1536-1800

The accession to the English throne of the Tudor dynasty, with its Welsh origins, transforms Wales from a conquered territory to an integral part of the English kingdom. The change is acknowledged in an act of parliament passed in 1536, with modifications added in 1543.

The practical purpose of these acts is to give Wales an adminstrative system, based on counties, which is compatible with that of England. It replaces the earlier feudal territories, granted to marcher lords for the purpose of subduing the hostile Welsh. Wales becomes, as a result of these changes, a principality within the English kingdom. From the Reformation onwards, its political story merges with that of England.

Welsh language and literature: from the 16th c. AD

The Reformation, with its emphasis on receiving the word of God in one's own language, brings great benefit to Wales. In the mid-16th there are fewer than 250,000 inhabitants of the principality, yet the Protestant government of Elizabeth I is persuaded to pass an act providing for a Welsh translation of the Anglican liturgy and of the Bible.

The Book of Common Prayer and the New Testament are published in Welsh in 1567. The complete Bible follows in 1588. Both provide an invaluable focus for the Welsh language - the only version of Celtic to remain a living tongue for a large community within the British isles, in an unbroken tradition surviving to the present day.

At the same period as the Reformation, the attitudes of the Renaissance have a beneficial effect on Welsh literature. The Renaissance passion for rediscovering classical texts becomes, in the Welsh context, a scholarly interest in the region's great bardic tradition of oral poetry. Important works are published in the 16th century, analyzing the grammar of the Welsh language and the rules of bardic poetry.

There are periods when the interest in these traditions slackens. And inevitably immigration and other pressures (such as the use of English in schools) gradually reduce the percentage of the population for whom Welsh is the first language.

Nevertheless the figures remain amazingly high. From a Welsh-speaking 54% of the population in 1891, the proportion reduces to 37% in 1921, 26% in 1961 and 20% in 1991. This present-day 20% amounts to about half a million people - more than have spoken Welsh at most periods in the past, and sufficient in number to be provided with radio and television in their own language.

The rediscovery of the bardic past gathers new vigour during the 19th century, answering the twin needs of Welsh nationalism and the contemporary fascination with everything medieval. Soon after Scott popularizes medieval Scotland, Charlotte Guest does something similar for Wales with her translation in 1839-49 of the Mabinogion.

The Mabinogion is a collection of eleven tales, based on the ancient oral tradition but written in prose between the 11th and 13th century for recital at the courts of Welsh princes. The tales survive in two manuscripts of the 14th-15th century, the White Book of Rhydderch and the Red Book of Hergest.

The expression of the Welsh identity through language, literature and music is seen above all in the tradition of the eisteddfod. Competitions between bards were common in the Middle Ages. The first assembly (the meaning of eisteddfod) to combine both musical and literary contests is generally considered to be a Christmas gathering held in Cardigan castle in 1176 by Rhys ap Gruffudd.

The interest in eisteddfods (or in Welsh eisteddfodau) declines during the 16th and 17th centuries but is revived in the late 18th century - spurred on by the Cymmrodorion Society, a group of homesick Welshmen living in London. Their enthusiasm leads to regional eisteddfods being held throughout Wales, followed by the decision taken, in Denbigh in 1860, to establish a national body to be known as The Eisteddfod. As a result the first official National Eisteddfod was held in Aberdare in 1861. Now an annual event, it ends each year with the chairing of the bard, the poet whose work in the traditional bardic form has won the top prize.

But the 18th century does more than revive the eisteddfod. It provides a magnficent new outlet for Welsh musical talent with the arrival of Methodism.

Methodism and the chapel choir: from the 18th century

Wales is one of the earliest centres of the evangelical revival in Britain. While the Wesley brothers are still at Oxford, a Welsh layman, Howel Harris, experiences a sudden revelation in 1735 which sends him on the road as an itinerant preacher. From 1737 he teams up with a like-minded curate, Daniel Rowlands. The two are already making a stir in Wales when the Methodist George Whitefield joins them for a few months during 1739.

Methodism, with its richly emotional appeal, suits the Welsh - though the influence of Whitefield means that they adopt the harsher Calvinist variety, emphasizing predestination (an issue on which Whitefield differs from the Wesleys).

Just as Charles Wesley provides the English Methodists with an abundance of satisfying hymns and tunes, so an early Methodist minister, William Williams, does the same for the Welsh (he is the author of more than 800 hymns).

Within this new communal tradition the all-male chapel choir becomes one of the most characteristic of Welsh institutions. The chapel itself is the centre of social and cultural life - particularly in the isolated valleys which acquire a new prosperity during the 19th century on account of their coal.

Coal and iron: 19th - 20th century AD

Wales is well equipped with raw materials for the developing Industrial Revolution. Abundant supplies are available locally to meet the new demand for iron (particularly for railway lines) and for coal (to fuel the furnaces of iron works, railway engines and steamships).

The Welsh supply of coal outlasts the iron, so from the mid-19th century new iron and steel works are established near the harbours of the south coast, round Swansea, Cardiff and Newport. Here foreign ore can be imported, while coal to fuel the furnaces can be fetched the short distance from the mining valleys which run up into the hills.

Wales History & Monarchs

Courtesy of Wiki

Wales-Ruler-K&Q-1

Deheubarth was founded circa 920 by Hywel Dda("Hywel the Good") out of the territories of Seisyllwg and Dyfed, both of which had come into his possession. Later on, the Kingdom of Brycheiniog would also be added to its territory. The chief seat of the rulers of Deheubarth and its traditional capital was at Dinefwr (although Carmarthen and Cardigan also served as the kingdom's capital for certain periods).

Deheubarth, like several other Welsh Petty kingdoms, continued to exist until the Norman Conquest of Wales, but constant power struggles meant that only for part of the time was it a separate entity with an independent ruler. It was annexed by Llywelyn ap Seisyll of Gwynedd in 1018, then by Rhydderch ab Iestyn of Morgannwg in 1023. Llywelyn ap Sisyll's son, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn again annexed Deheubarth and became ruler of most of Wales, but after his death the old Dinefwr dynasty regained power.

In the arena of the church, Sulien was the leader of the monastic community at Llanbadarn Fawr in Ceredigion. Born ca. 1030, he became Bishop of St. David's in 1073. Both of his sons followed him into the service of the church. (At this time the prohibition against the marriage of clerics was not yet established.) His sons produced a number of manuscripts and original Latin and vernacular poems. They were very active in the ecclesiastical and political life of Deheubarth. One son, Rhygyfarch (known as Ricemarch in Latin) of Llanbadarn Fawr wrote the Life of Saint David, and another, Ieuan, was a skillful scribe and illuminator. He copied some the works of Augustine of Hippo and may have written the Life of St Padarn.

Rhys ap Tewdwr ruled from 1078 to 1093 and was able to fight off several attempts to dethrone him, considerably increasing the power of the kingdom. However the Normans were now encroaching on the eastern borders of Deheubarth, and in 1093 Rhys was killed in unknown circumstances while resisting their expansion in Brycheiniog . This led to the Norman conquest of most of his kingdom, with his son Gruffydd ap Rhys temporarily reduced to being a fugitive. Gruffydd did eventually become prince of a small part of his father's kingdom, but most was carved up into various Norman lordships.

There was a general Welsh revolt against the Normans in 1136, following the death of Henry II , and Gruffydd formed an alliance with Gwynedd. Together with Owain Gwynedd and Cadwaladr ap Gruffydd of Gwynedd he won a victory against the Normans at the Battle of Crug Mawr near Cardigan. This liberated Ceredigion from Norman rule, but, though it had historically been part of Deheubarth, it was taken over by Gwynedd, the senior partner in the alliance. Gruffydd was killed in unknown circumstances the following year.

The rule of Deheubarth now fell to Gruffydd's sons, of whom four, Anarawd, Cadell, Maredudd and Rhys ap Gruffydd ruled in turn. The death of a ruler frequently led to disunity and struggles for supremacy, but the four brothers worked together to win back their grandfather's kingdom from the Normans and to expel Gwynedd from Ceredigion. Of the first three, only Cadell reigned for more than a few years, but the youngest of the four, Rhys ap Gruffydd (The Lord Rhys), ruled from 1155 to 1197, and after Owain Gwynedd's death in 1170 made Deheubarth the most powerful of the Welsh kingdoms.

Upon Rhys ap Gruffydd's death in 1197, the kingdom was split between several of his sons, and Deheubarth never again rivalled the power of Gwynedd. The early 13th century princes of Deheubarth usually appear as clients of Llywelyn the Great of Gwynedd. Following the defeat of the princes of Gwynedd and the division of their realm authorised by the Statute of Rhuddlan, Deheubarth was divided into the historic counties of Cardiganshire, Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire.

Deheubarth, like several other Welsh Petty kingdoms, continued to exist until the Norman Conquest of Wales, but constant power struggles meant that only for part of the time was it a separate entity with an independent ruler. It was annexed by Llywelyn ap Seisyll of Gwynedd in 1018, then by Rhydderch ab Iestyn of Morgannwg in 1023. Llywelyn ap Sisyll's son, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn again annexed Deheubarth and became ruler of most of Wales, but after his death the old Dinefwr dynasty regained power.

In the arena of the church, Sulien was the leader of the monastic community at Llanbadarn Fawr in Ceredigion. Born ca. 1030, he became Bishop of St. David's in 1073. Both of his sons followed him into the service of the church. (At this time the prohibition against the marriage of clerics was not yet established.) His sons produced a number of manuscripts and original Latin and vernacular poems. They were very active in the ecclesiastical and political life of Deheubarth. One son, Rhygyfarch (known as Ricemarch in Latin) of Llanbadarn Fawr wrote the Life of Saint David, and another, Ieuan, was a skillful scribe and illuminator. He copied some the works of Augustine of Hippo and may have written the Life of St Padarn.

Rhys ap Tewdwr ruled from 1078 to 1093 and was able to fight off several attempts to dethrone him, considerably increasing the power of the kingdom. However the Normans were now encroaching on the eastern borders of Deheubarth, and in 1093 Rhys was killed in unknown circumstances while resisting their expansion in Brycheiniog . This led to the Norman conquest of most of his kingdom, with his son Gruffydd ap Rhys temporarily reduced to being a fugitive. Gruffydd did eventually become prince of a small part of his father's kingdom, but most was carved up into various Norman lordships.

There was a general Welsh revolt against the Normans in 1136, following the death of Henry II , and Gruffydd formed an alliance with Gwynedd. Together with Owain Gwynedd and Cadwaladr ap Gruffydd of Gwynedd he won a victory against the Normans at the Battle of Crug Mawr near Cardigan. This liberated Ceredigion from Norman rule, but, though it had historically been part of Deheubarth, it was taken over by Gwynedd, the senior partner in the alliance. Gruffydd was killed in unknown circumstances the following year.

The rule of Deheubarth now fell to Gruffydd's sons, of whom four, Anarawd, Cadell, Maredudd and Rhys ap Gruffydd ruled in turn. The death of a ruler frequently led to disunity and struggles for supremacy, but the four brothers worked together to win back their grandfather's kingdom from the Normans and to expel Gwynedd from Ceredigion. Of the first three, only Cadell reigned for more than a few years, but the youngest of the four, Rhys ap Gruffydd (The Lord Rhys), ruled from 1155 to 1197, and after Owain Gwynedd's death in 1170 made Deheubarth the most powerful of the Welsh kingdoms.

Upon Rhys ap Gruffydd's death in 1197, the kingdom was split between several of his sons, and Deheubarth never again rivalled the power of Gwynedd. The early 13th century princes of Deheubarth usually appear as clients of Llywelyn the Great of Gwynedd. Following the defeat of the princes of Gwynedd and the division of their realm authorised by the Statute of Rhuddlan, Deheubarth was divided into the historic counties of Cardiganshire, Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire.

Medieval Kingdoms of Wales

Deheubarth

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

5. Menu

Pages

Member NCMD