Historic - Reference

Powered By Sispro1

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

How Roman London Became Britain's Capital

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Complimentary Topics

The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

© Provided by The Independent

A brutal blood-soaked bid to wipe London off the map was a key factor that led to the city first emerging as Britain's capital.

New archaeological research is showing that London's elevated status stemmed partly from a Roman military and political reaction to Boadicea's violent destruction of London and other key cities in the mid 1st century AD.

The investigation, carried out by Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), suggests that the Romans shifted the capital of their British province from Colchester to London shortly after her revolt.

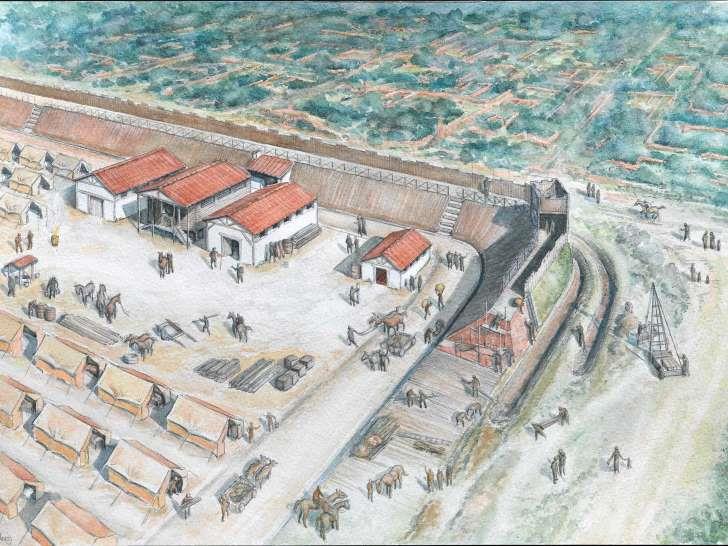

A key piece of new evidence is MOLA research, showing that the Roman military built a fort in London immediately after Boadicea (more accurately known as Boudicca) had been defeated – but did not seem to have built an equivalent one in what had, up till then, been Roman Britain’s provincial capital, Colchester. The research on the 125 by 90 metre playing-card-shaped fort will be published for the first time today by MOLA as a 263 page book – An early Roman fort and urban development on Londinium’s eastern hill. It was located just west of modern Mincing Lane, 230 metres north-east of the northern end of Roman era London Bridge. Archaeologists believe that it would have accommodated between 500 and 800 troops – a mixture of legionaries and auxiliaries and of infantry and cavalry.

“The research on the fort is hugely significant for how we understand the early development and growth of London – and how, why and when it first became Britain’s capital,” said Julian Hill, a senior archaeologist at Museum of London Archaeology.

Archaeologists studying the new fort believe the Romans decided that London had the strategic and logistical edge over Colchester, previously the provincial capital© The Independent Archaeologists studying the new fort believe the Romans decided that London had the strategic and logistical edge over Colchester, previously the provincial capital What's more, quite separate work by British and other scholars now hints at the possibility that, at the same time or shortly after the fort was built, a huge temple to the Imperial cult may well have been constructed in London. One of the key symbols of Colchester's status as the province's pre-revolt capital had been its Imperial cult temple – but that building was partly destroyed during the rebellion, and although it was at some stage repaired, some inscriptional evidence from London suggests the possibility that post-revolt Colchester had to share the Imperial cult role with London.

With the new fort, archaeologists now believe that, in the aftermath of the revolt, the Romans chose London as their new British political headquarters.

With the new fort, archaeologists now believe that, in the aftermath of the revolt, the Romans chose London as their new British political headquarters.

It had three key strategic, mercantile and political advantages over Colchester. First of all it was the nearest point to the sea that the Thames could easily be bridged. The first London Bridge (just a few metres east of the modern one) had been built by the Roman military, probably in 48 A.D. Secondly, unlike Colchester, seagoing ships could reach London and unload their freight there. And thirdly, again unlike Colchester which had been a major British tribal capital, London was a totally Roman 'new build' city that therefore had no tribal political baggage or implications to be taken into account.

It seems that immediately after the Roman conquest had begun in 43 A.D., the then Emperor, Claudius, was keen to impress (and co-opt the status of) Britain's most powerful tribal confederation, the Trinovantes by building his first great Roman fortress there – and making it the capital of the province. But, in 60 A.D., when both Colchester and London were both destroyed in the Boudiccan revolt, the Roman authorities appear to have decided that strategic and logistical factors should now determine where their political headquarters and provincial capital should be – and London was then developed far more assiduously than Colchester.

Indeed, within 15 years of the defeat of Boudicca and the upgrading of London, the city experienced huge levels of imperial investment – including a large forum, a public baths complex, an amphitheatre, major port facilities and other major buildings - probably temples.

So rapid was the city's growth (and the consequent demand for residential and commercial real estate), that in around 75 A.D., the Roman authorities appear to have decided to relocate London's fort. certainly by around 120 A.D., a new fort had been built at the north-western edge of the burgeoning city – in what is now Cripplegate.

The huge military and therefore political importance of London in the post-Boudicca era was not just because of its fort. Archaeologists now think it is likely that most military hardware was channelled into Britain via London. And on the back of that very substantial military transport operation, mainly conducted by private vessels subcontracted by the military, a large-scale civilian mercantile trade rapidly developed.

Archaeological research is shedding light on the nature and scale of both the military and civil operations.

An analysis of finds from the post-Boudiccan fort (which operated from around 61 A.D. to around 75 A.D.) shows the sort of military hardware the troops there were being supplied with – everything from armour, spears and shields to horse fittings, oil lamps and writing equipment. In total, around 60 military items have been identified from the fort so far. However archaeologists have, over the years, also found large quantities of broken military equipment which the Romans had used as part of landfill to raise ground levels on marshy land 400 metres west of the fort. So far, well over 500 fragments of Roman helmet, armour, weaponry and cavalry equipment – all potentially from the post-Boudiccan fort. It is the largest corpus of Roman military equipment ever found in Britain.

There's even some evidence – Celtic style metalwork – from the fort area and the landfill, suggesting that native British auxiliary troops from friendly tribes may have formed part of the post-Boudiccan London garrison

The newly re-examined evidence suggesting the possibility that London became a centre for the Imperial cult soon after the Boudiccan revolt is also potentially very significant. It consists of an inscription and two pieces of sculpture. Two items of sculpture (a marble head and a bronze arm) are from imperial statues, probably of the Emperor Nero – and almost certainly date from the 60s A.D.

But it is the inscription which is the strongest indicator that London had a large Imperial cult temple. The inscription, in honour of the divine spirit of the emperor, was on a statue plinth which appears originally to have been around 2 metres wide and 1.4 metres high. The unusually large size of this probable plinth strongly suggests that it supported a bronze statue of truly monumental proportions – potentially double life-size.

Underlining the political significance of this once-great statue is a part of the inscription which suggests that it was erected by Roman Britain's provincial council – the province's rubber-stamp 'parliament' which was responsible for administering the Imperial cult. Strangely, the inscription and the remains of the plinth it was inscribed on, have always been largely ignored by the archaeological world – mainly because the object was found in 1850, but unfortunately lost by 1859.

Only a drawing has survived. However it is known that it was re-used in a later wall, located only around 150 metres from a particularly large probable riverside temple built in around 75 A.D. In terms of wording, the style of the inscription is, in some respects, unparalleled – arguably because of its probable early (i.e. potentially 1st century) date. One particular possible rendering of the wording of the inscription would have been especially appropriate for the specific political circumstances of the 70s A.D. It is also known from Roman classical sources that during the period 69-81 A.D. a particularly large number of imperial statues were erected in Britain.

It seems that immediately after the Roman conquest had begun in 43 A.D., the then Emperor, Claudius, was keen to impress (and co-opt the status of) Britain's most powerful tribal confederation, the Trinovantes by building his first great Roman fortress there – and making it the capital of the province. But, in 60 A.D., when both Colchester and London were both destroyed in the Boudiccan revolt, the Roman authorities appear to have decided that strategic and logistical factors should now determine where their political headquarters and provincial capital should be – and London was then developed far more assiduously than Colchester.

Indeed, within 15 years of the defeat of Boudicca and the upgrading of London, the city experienced huge levels of imperial investment – including a large forum, a public baths complex, an amphitheatre, major port facilities and other major buildings - probably temples.

So rapid was the city's growth (and the consequent demand for residential and commercial real estate), that in around 75 A.D., the Roman authorities appear to have decided to relocate London's fort. certainly by around 120 A.D., a new fort had been built at the north-western edge of the burgeoning city – in what is now Cripplegate.

The huge military and therefore political importance of London in the post-Boudicca era was not just because of its fort. Archaeologists now think it is likely that most military hardware was channelled into Britain via London. And on the back of that very substantial military transport operation, mainly conducted by private vessels subcontracted by the military, a large-scale civilian mercantile trade rapidly developed.

Archaeological research is shedding light on the nature and scale of both the military and civil operations.

An analysis of finds from the post-Boudiccan fort (which operated from around 61 A.D. to around 75 A.D.) shows the sort of military hardware the troops there were being supplied with – everything from armour, spears and shields to horse fittings, oil lamps and writing equipment. In total, around 60 military items have been identified from the fort so far. However archaeologists have, over the years, also found large quantities of broken military equipment which the Romans had used as part of landfill to raise ground levels on marshy land 400 metres west of the fort. So far, well over 500 fragments of Roman helmet, armour, weaponry and cavalry equipment – all potentially from the post-Boudiccan fort. It is the largest corpus of Roman military equipment ever found in Britain.

There's even some evidence – Celtic style metalwork – from the fort area and the landfill, suggesting that native British auxiliary troops from friendly tribes may have formed part of the post-Boudiccan London garrison

The newly re-examined evidence suggesting the possibility that London became a centre for the Imperial cult soon after the Boudiccan revolt is also potentially very significant. It consists of an inscription and two pieces of sculpture. Two items of sculpture (a marble head and a bronze arm) are from imperial statues, probably of the Emperor Nero – and almost certainly date from the 60s A.D.

But it is the inscription which is the strongest indicator that London had a large Imperial cult temple. The inscription, in honour of the divine spirit of the emperor, was on a statue plinth which appears originally to have been around 2 metres wide and 1.4 metres high. The unusually large size of this probable plinth strongly suggests that it supported a bronze statue of truly monumental proportions – potentially double life-size.

Underlining the political significance of this once-great statue is a part of the inscription which suggests that it was erected by Roman Britain's provincial council – the province's rubber-stamp 'parliament' which was responsible for administering the Imperial cult. Strangely, the inscription and the remains of the plinth it was inscribed on, have always been largely ignored by the archaeological world – mainly because the object was found in 1850, but unfortunately lost by 1859.

Only a drawing has survived. However it is known that it was re-used in a later wall, located only around 150 metres from a particularly large probable riverside temple built in around 75 A.D. In terms of wording, the style of the inscription is, in some respects, unparalleled – arguably because of its probable early (i.e. potentially 1st century) date. One particular possible rendering of the wording of the inscription would have been especially appropriate for the specific political circumstances of the 70s A.D. It is also known from Roman classical sources that during the period 69-81 A.D. a particularly large number of imperial statues were erected in Britain.

Courtesy:14.05.16

The Independent

David Keys

The Independent

David Keys

Pages

Member NCMD

Reference Menu