The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

Powered By Sispro1

Vikings of Middle England Coins - Numismatics,

For Reference ONLY

Everything For The Detectorist

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

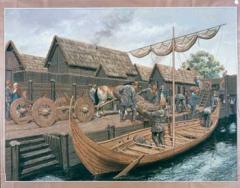

Courtesy: York Museums Trust Project 14.02.18

Back- Viking-Coins-History-1 <<<

The Vikings

Timeline

Timeline

Anglo-Saxon Timeline

Pages

Anglian York

Anglo-Saxons were living in and around York by the late 400s: we know that from cemetery remains. But it is only from about 600 that there is clear evidence of the city’s status.

During this period the four great Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria were defined and Christianity was re-established.

The York settlement was called Eoforwic, which suggests it was a place of some significance. The ‘wics’ were seemingly the most important commercial centres in each of the kingdoms - others were Lundenwic (London) and Gipeswic (Ipswich).

York scholar Alcuin, meanwhile, described his home town as an emporium, a seat of commerce by land and sea, and another writer mentions a colony of international merchants living in or near the city.

The main gateways through the Roman fortress defences meant that the streets linking them were preserved, however new streets started criss-crossing the city as Roman buildings fell away. Goodramgate and Blake Street are two examples.

There may have been a major Anglian church on the site of St Mary Castlegate, next to the place that the wonderful York Helmet was found during the Coppergate excavations. The helmet has been dated to about 750 to 775. Evidence of a settlement from around 700 to 850 was discovered not far away at Fishergate - at the junction of rivers Ouse and Foss. Timber buildings about 13m by 6m stood within a plot of 1,200 square metres. Associated ditches, rubbish pits, wells and latrines were nearby. There is also evidence of manufacture from raw materials including iron, lead, copper, wool, leather and bone.

Early Christian York

In 601, Pope Gregory decided to send a mission to convert the British to Christianity. He selected York to be the church's centre in the north.

Why York? His choice may well hark back to Roman times. Constantine, who was declared Roman emperor in York, later decreed toleration of Christianity, and the city was a bishopric in the 4th century.

On a more practical level, the surviving Roman roads made travel to York easier.

A generation after the Pope s decree his missionary Bishop Paulinus arrived. We cannot be sure what he found there - a thriving settlement or a largely abandoned city.

Whatever its state, York lay within the Northumbrian kingdom of Deira. King Edwin of Deira was apparently persuaded to convert after a successful campaign against the rival kingdom of Wessex. He did so in a small, purpose-built wooden church dedicated to St Peter on Easter Sunday, 627.

Edwin rebuilt his church in stone. It would probably have become home to an archbishop if the king hadn t died in battle in about 633. His death saw Paulinus flee to Kent with Edwin s queen. One of Paulinus s companions, James the Deacon, apparently remained in York but the bishop s seat moved to Lindisfarne in Northumberland. The bishopric was restored in York by the first synod which was held at Whitby in 664. In 735 York did finally became an archbishopric when Egbert became the first northern Archbishop.

Later Archbishop Ethelberht built Holy Wisdom church, said to be magnificent - unfortunately it isn t clear where it was.

Writings by Bede and Alcuin reveal that York was by now a city of churches. It is thought that a monastic precinct had been created in Bishophill within which there were several churches.

Viking Invasion

Led by Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless, the Viking army attacked on November 1 866. This date may well have been chosen with care. It was All Saints Day, an important festival in York when many of the town s leaders could have been in the cathedral, making a surprise attack even more effective.

It worked. They took York, although the Northumbrian kings Aelle and Osbert were not captured.

The Viking army spent the winter on the Tyne and had to recapture York in March 867. This was a more violent clash. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles recorded that there was an excessive slaughter made of the Northumbrians . Among those killed were Aelle and Osbert.

After a series of campaigns against other kingdoms, part of the great Viking army returned to Northumbria in 876. According to Anglo Saxon chronicles, Halfdan shared out the lands of the Northumbrians and they proceeded to plough and to support themselves .

Two years later King Alfred of Wessex agreed a truce with Viking king Guthrum which saw England divided into the Anglo-Saxon southern kingdom and the Danelaw. The Danelaw, under Viking control, included counties north of an imaginary line running from London to Bedford and then up to Chester. It was England s first north-south divide.

A history written 150 years later records how the Viking army rebuilt the city of York, cultivated the land around it, and remained there .

Eoforwic had become Jorvik, and was soon transformed into the capital of a kingdom of the same name, roughly corresponding to Yorkshire today.

Who Were the Vikings?

Vikings were sea-borne Scandinavians. Some carried out raids in the early years of the Viking age. Later they undertook systematic campaigns of conquest with well-trained armies.

But for all their reputation as fearsome warriors, many more Vikings explored, traded and settled peacefully in other parts of Europe. After the initial invasion there is little evidence of York being a warrior community - no warrior graves have been found in the city and very little weaponry.

Fishermen and farmers, vikings were a self-sufficient people who could take full advantage of what nature provided. Vikings fashioned intricate tools and were skilled craftsmen.

So why did the Vikings undertake hazardous sea journeys in longships to Britain and other parts of Europe? It may have been that a population increase allowed more men to leave their farms and travel further afield. These expeditions coincided with rapid and significant improvements in boat building.

Another reason was to amass wealth. Many towns boasted impressive assets, from farming produce and raw materials to precious church possessions like lavishly-decorated manuscripts. That made them lucrative targets.

Later many Vikings chose to settle in these lands, rather than return home with their loot. This is what happened in and around York.

Life in Viking York

York changed when it was captured by the Vikings and the city became known as Jorvik.

The Anglian site at the junction of the rivers was abandoned in the mid-9th century. By contrast the street known as Coppergate sprang back to life at this time, after seemingly being unoccupied for the previous 450 years.

We have learned a great deal about life in Jorvik from the excavation of the Coppergate site.

Single-storey properties with wattle walls and thatched roofs were used as both homes and workshops. The buildings were typically about 7m x 5m with a large central hearth dominating the inside. The floors were made of trampled earth.

Later Viking buildings had more timber and small basements, around 2m deep, perhaps for storage.

These were built in two ranks along Coppergate: space was at a premium in this booming city.

As a result Jorvik people lived cheek-by-jowl. Living conditions were squalid. Human fleas and lice were found at Coppergate. Rubbish was thrown out in back yards, a fetid mix of discarded builidng materials, food remains and human waste. These deposits saw the ground level rise by around 1cm a year. But they also provided the perfect conditions to preserve the Viking way of life for the benefit of historians hundreds of years later.

Viking Industry and Trade

Manufactured objects in Jorvik were plentiful and surprisingly uniform. Specialist workers undertook an early version of mass production.

Standardised pots were made a fast wheel fired in a regulated kiln. Wooden cups were systematically produced by lathe-turners. Several properties in Coppergate were given over to metalworking. One is believed to have been a blacksmith s workshop. Knives, keys and jewellery were produced. Vikings were competent in these high-temperature industries, working with lead, copper-alloy, iron, silver and gold. They even made glass.

Materials travelled many miles to reach the Jorvik craftsmen: gold and silver came from Europe, copper and lead from the Pennines, and tin from Cornwall. Beads and rings were fashioned from amber and jet. Specialists could carve out combs, pins and even ice skates from bones and antlers. Shoes, clothes and textiles were made out of leather.

All of this thriving industry required plenty of raw materials and customers. Most of the food and raw materials needed by Jorvik s inhabitants were available in the immediate surrounding areas. Everything from iron ore to wool to antlers were brought to Jorvik from Yorkshire s countryside estates. The finished products by York s craftsmen would make the return journey, sold in the region.

The Vikings were great traders and had also established links from the Caspian Sea and Black Sea in the east, across Russia to Iceland, Greenland and Newfoundland. This ensured a range of exotic goods arrived in York: walrus ivory, silk for headscarves, amber for jewellery and Rhineland wine. Spices, oils and perfumes were probably imported too. Jorvik was both bustling marketplace and cosmopolitan hotspot.

The Viking Kingdom England in 878

For the best part of a century large parts of the north and east of England were ruled by Viking kings based in York. On the other side of an unstable boundary, the south and west were held by a succession of English kings.

Before 850 Viking attacks had been short and sharp but in that year for the first time they stayed in Britain through the winter, on the Isle of Thanet near London. By 866 they were well established and had gathered a great army. That year they marched north and took an incredible prize, the royal city at the heart of the kingdom of Northumbria - York.

In 870 the kingdom of East Anglia fell to the Vikings and Mercia followed in 874. In the following years the Vikings secured the land around York, settling and farming it. York itself was now effectively the capital of a new Viking kingdom - the Danelaw.

The borders were never very clear nor secure and the Viking kings faced attacks from both the Saxons in the north and the English kings, particularly of Wessex in the south. Indeed one English king, Athelstan, took control of York in 927 and was the accepted ruler of most of the country until his death in 940. For the next 15 years, York was again ruled by a succession of Viking kings.

The last of these was the famous Eric Bloodaxe who was defeated in 954. From then on, York and Northumbria were always part of a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom.

Anglo-Saxons were living in and around York by the late 400s: we know that from cemetery remains. But it is only from about 600 that there is clear evidence of the city’s status.

During this period the four great Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria were defined and Christianity was re-established.

The York settlement was called Eoforwic, which suggests it was a place of some significance. The ‘wics’ were seemingly the most important commercial centres in each of the kingdoms - others were Lundenwic (London) and Gipeswic (Ipswich).

York scholar Alcuin, meanwhile, described his home town as an emporium, a seat of commerce by land and sea, and another writer mentions a colony of international merchants living in or near the city.

The main gateways through the Roman fortress defences meant that the streets linking them were preserved, however new streets started criss-crossing the city as Roman buildings fell away. Goodramgate and Blake Street are two examples.

There may have been a major Anglian church on the site of St Mary Castlegate, next to the place that the wonderful York Helmet was found during the Coppergate excavations. The helmet has been dated to about 750 to 775. Evidence of a settlement from around 700 to 850 was discovered not far away at Fishergate - at the junction of rivers Ouse and Foss. Timber buildings about 13m by 6m stood within a plot of 1,200 square metres. Associated ditches, rubbish pits, wells and latrines were nearby. There is also evidence of manufacture from raw materials including iron, lead, copper, wool, leather and bone.

Early Christian York

In 601, Pope Gregory decided to send a mission to convert the British to Christianity. He selected York to be the church's centre in the north.

Why York? His choice may well hark back to Roman times. Constantine, who was declared Roman emperor in York, later decreed toleration of Christianity, and the city was a bishopric in the 4th century.

On a more practical level, the surviving Roman roads made travel to York easier.

A generation after the Pope s decree his missionary Bishop Paulinus arrived. We cannot be sure what he found there - a thriving settlement or a largely abandoned city.

Whatever its state, York lay within the Northumbrian kingdom of Deira. King Edwin of Deira was apparently persuaded to convert after a successful campaign against the rival kingdom of Wessex. He did so in a small, purpose-built wooden church dedicated to St Peter on Easter Sunday, 627.

Edwin rebuilt his church in stone. It would probably have become home to an archbishop if the king hadn t died in battle in about 633. His death saw Paulinus flee to Kent with Edwin s queen. One of Paulinus s companions, James the Deacon, apparently remained in York but the bishop s seat moved to Lindisfarne in Northumberland. The bishopric was restored in York by the first synod which was held at Whitby in 664. In 735 York did finally became an archbishopric when Egbert became the first northern Archbishop.

Later Archbishop Ethelberht built Holy Wisdom church, said to be magnificent - unfortunately it isn t clear where it was.

Writings by Bede and Alcuin reveal that York was by now a city of churches. It is thought that a monastic precinct had been created in Bishophill within which there were several churches.

Viking Invasion

Led by Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless, the Viking army attacked on November 1 866. This date may well have been chosen with care. It was All Saints Day, an important festival in York when many of the town s leaders could have been in the cathedral, making a surprise attack even more effective.

It worked. They took York, although the Northumbrian kings Aelle and Osbert were not captured.

The Viking army spent the winter on the Tyne and had to recapture York in March 867. This was a more violent clash. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles recorded that there was an excessive slaughter made of the Northumbrians . Among those killed were Aelle and Osbert.

After a series of campaigns against other kingdoms, part of the great Viking army returned to Northumbria in 876. According to Anglo Saxon chronicles, Halfdan shared out the lands of the Northumbrians and they proceeded to plough and to support themselves .

Two years later King Alfred of Wessex agreed a truce with Viking king Guthrum which saw England divided into the Anglo-Saxon southern kingdom and the Danelaw. The Danelaw, under Viking control, included counties north of an imaginary line running from London to Bedford and then up to Chester. It was England s first north-south divide.

A history written 150 years later records how the Viking army rebuilt the city of York, cultivated the land around it, and remained there .

Eoforwic had become Jorvik, and was soon transformed into the capital of a kingdom of the same name, roughly corresponding to Yorkshire today.

Who Were the Vikings?

Vikings were sea-borne Scandinavians. Some carried out raids in the early years of the Viking age. Later they undertook systematic campaigns of conquest with well-trained armies.

But for all their reputation as fearsome warriors, many more Vikings explored, traded and settled peacefully in other parts of Europe. After the initial invasion there is little evidence of York being a warrior community - no warrior graves have been found in the city and very little weaponry.

Fishermen and farmers, vikings were a self-sufficient people who could take full advantage of what nature provided. Vikings fashioned intricate tools and were skilled craftsmen.

So why did the Vikings undertake hazardous sea journeys in longships to Britain and other parts of Europe? It may have been that a population increase allowed more men to leave their farms and travel further afield. These expeditions coincided with rapid and significant improvements in boat building.

Another reason was to amass wealth. Many towns boasted impressive assets, from farming produce and raw materials to precious church possessions like lavishly-decorated manuscripts. That made them lucrative targets.

Later many Vikings chose to settle in these lands, rather than return home with their loot. This is what happened in and around York.

Life in Viking York

York changed when it was captured by the Vikings and the city became known as Jorvik.

The Anglian site at the junction of the rivers was abandoned in the mid-9th century. By contrast the street known as Coppergate sprang back to life at this time, after seemingly being unoccupied for the previous 450 years.

We have learned a great deal about life in Jorvik from the excavation of the Coppergate site.

Single-storey properties with wattle walls and thatched roofs were used as both homes and workshops. The buildings were typically about 7m x 5m with a large central hearth dominating the inside. The floors were made of trampled earth.

Later Viking buildings had more timber and small basements, around 2m deep, perhaps for storage.

These were built in two ranks along Coppergate: space was at a premium in this booming city.

As a result Jorvik people lived cheek-by-jowl. Living conditions were squalid. Human fleas and lice were found at Coppergate. Rubbish was thrown out in back yards, a fetid mix of discarded builidng materials, food remains and human waste. These deposits saw the ground level rise by around 1cm a year. But they also provided the perfect conditions to preserve the Viking way of life for the benefit of historians hundreds of years later.

Viking Industry and Trade

Manufactured objects in Jorvik were plentiful and surprisingly uniform. Specialist workers undertook an early version of mass production.

Standardised pots were made a fast wheel fired in a regulated kiln. Wooden cups were systematically produced by lathe-turners. Several properties in Coppergate were given over to metalworking. One is believed to have been a blacksmith s workshop. Knives, keys and jewellery were produced. Vikings were competent in these high-temperature industries, working with lead, copper-alloy, iron, silver and gold. They even made glass.

Materials travelled many miles to reach the Jorvik craftsmen: gold and silver came from Europe, copper and lead from the Pennines, and tin from Cornwall. Beads and rings were fashioned from amber and jet. Specialists could carve out combs, pins and even ice skates from bones and antlers. Shoes, clothes and textiles were made out of leather.

All of this thriving industry required plenty of raw materials and customers. Most of the food and raw materials needed by Jorvik s inhabitants were available in the immediate surrounding areas. Everything from iron ore to wool to antlers were brought to Jorvik from Yorkshire s countryside estates. The finished products by York s craftsmen would make the return journey, sold in the region.

The Vikings were great traders and had also established links from the Caspian Sea and Black Sea in the east, across Russia to Iceland, Greenland and Newfoundland. This ensured a range of exotic goods arrived in York: walrus ivory, silk for headscarves, amber for jewellery and Rhineland wine. Spices, oils and perfumes were probably imported too. Jorvik was both bustling marketplace and cosmopolitan hotspot.

The Viking Kingdom England in 878

For the best part of a century large parts of the north and east of England were ruled by Viking kings based in York. On the other side of an unstable boundary, the south and west were held by a succession of English kings.

Before 850 Viking attacks had been short and sharp but in that year for the first time they stayed in Britain through the winter, on the Isle of Thanet near London. By 866 they were well established and had gathered a great army. That year they marched north and took an incredible prize, the royal city at the heart of the kingdom of Northumbria - York.

In 870 the kingdom of East Anglia fell to the Vikings and Mercia followed in 874. In the following years the Vikings secured the land around York, settling and farming it. York itself was now effectively the capital of a new Viking kingdom - the Danelaw.

The borders were never very clear nor secure and the Viking kings faced attacks from both the Saxons in the north and the English kings, particularly of Wessex in the south. Indeed one English king, Athelstan, took control of York in 927 and was the accepted ruler of most of the country until his death in 940. For the next 15 years, York was again ruled by a succession of Viking kings.

The last of these was the famous Eric Bloodaxe who was defeated in 954. From then on, York and Northumbria were always part of a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom.

Information Data

Main Coin Menu

Viking to Anglo-Saxon Menu

Member NCMD

V. Menu