The Paragon Of Metal Detecting

& Archaeology

& Archaeology

Powered By Sispro1

Normans of Middle England Coins - Numismatics,

For Reference ONLY

Everything For The Detectorist

Copyright All Rights Reserved by Nigel G Wilcox E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Designed by Nigel G Wilcox

Courtesy: York Museums Trust Project 14.02.18

- Normans-Coins-History-1 <<<

Anglo Scandinavian York

The period of York's history between the demise of Eric Bloodaxe in 954 and the arrival of the Normans in 1068 is known as the Anglo-Scandinavian. York was ruled by an English king but was still heavily influenced by viking culture.

It was in a period of relative peace. Eric's conqueror, the English king Eadred, died only a year later in 955 and was eventually succeeded by his nephew Edgar. Edgar was to rule England from 959-975, a time free from foreign attack so he became known as the Peaceable .

According to a contemporary account by this time York was a major city of 30,000 citizens. The city is crammed beyond expression, the account states, and enriched with treasures of merchants, who come from all parts, but above all from the Danish people.

Despite its importance, English kings rarely visited Jorvik. Instead they appointed earls to keep a grip on Northumbria. A story has it that Viking invader King Svein Forkbeard of Denmark was buried in York in 1014.

The Vikings had been good for York, turning it into a thriving, bustling conurbation. By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, York was second only to London in size and prosperity.

The Normans Arrive

Previous southern kings had been content to let the north be. Not so William the Conqueror.

After 1066 York was ‘seething with discontent’, in the words of chronicler Orderic Vitalis. It was a Viking city, with Viking traditions and culture. More than that the whole of the north was in rebellion. So William marched on York in 1068.

William intended to make this large and prosperous city a part of his kingdom.

As he approached, leading citizens gave him hostages and the keys to the city.

But William was determined to stamp his authority on York. He began by building a castle, followed by a second in 1069, leaving 500 knights as a garrison. The city’s continuing importance was thus confirmed - it was the only place in the country with two castles outside London.

York's two Norman castles were designed to control access to the city by river: they were sited on eith side of the Ouse, one at Clifford's Tower and the other at Baille Hill. A chain could be threaded between them to prevent passage on the river.

William was right to be cautious - there was still unrest in the north.

Rebellion and Revenge

To make room for one of his castles, William the Conqueror laid waste to one of the seven shires of York. This only added to the anger and resentment in the city.

In 1069 local forces attacked the two castles without success. But then a more serious challenge emerged: King Swein of Denmark arrived with a large fleet of ships in August of that year. Together with powerful Anglo-Saxon nobles and the people of York, the force took the city, burning the castles to the ground and massacring the Norman occupiers.

Part of the Norman army s defence was to set fire to buildings that might offer shelter to the attackers: the blaze spread and a large part of the city was lost, including the Minster.

There is little evidence that the victors had planned a strategy for what to do when they re-took the city and victory was short lived.

William's Revenge

On hearing the news of his forces defeat at York, William swore a furious oath by the splendour of God to avenge himself on the north. He bribed the Danes to leave the city and advanced to York without opposition.

He repaired the two castles and then, using the city as a base, remorselessly and relentlessly carried out what was became known as the Harrying of the North .

The exact scale of the Harrying is unknown. But it was certainly devastating, with many thousands of deaths, from violence and famine.

Symeon of Durham recorded that 'It was horrible to observe, in houses, streets and roads, human corpses rotting...For no-one survived to cover them with earth, all having perished by the sword and starvation, or left the land of their fathers because of hunger.'

It may be that William later came to regret the scale of the destruction. Chronicler Orderic Vitalis wrote that the king confessed on his deathbed to having treated the native inhabitants of the kingdom with unreasonable severity, cruelly oppressed high and low, unjustly disinherited many, and caused the death of thousands by starvation and war, especially in Yorkshire .

Nevertheless the operation achieved his aim. The rebellion was defeated and the population subdued.

Norman Reconstruction

William stayed in York in Christmas 1069 and it must have been a depressing place. Most great buildings of the Viking age were gone or in ruins. The lively, prosperous capital of the north had been wrecked.

The reconstruction of military buildings began almost immediately. The two rebuilt castles towered over the surviving low houses and the ruined Minster, an unmistakable symbol of the power of the new king.

The city s defences were reinforced in a more unusual way. Near to the larger castle, at Clifford s Tower, a dam was constructed blocking the Foss. The resulting reservoir became known as the King s Fishpool, which provided an impenetrable barrier to the east of the city. This is why there is no wall to that side.

Civilian York took a longer to recover - of the 1,400 or so houses recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086, more than half were deserted and derelict.

However the defences weren t the only interest of the city s Norman rulers, they also embarked on a massive campaign of church building.

Norman Religious Buildings

The religious foundations laid by the Normans are perhaps their greatest legacy.

The last Anglo-Saxon Archbishop of York was Ealdred, who had crowned William the Conqueror at Westminster Abbey.

After Ealdred s death in 1070 a Norman, Thomas of Bayeux, was appointed Archbishop of York and became the single most powerful person in the city.

A New Minster

Thomas set about rebuilding the Minster, a task completed in about 1100. Although we don t know the exact location of the Anglo-Saxon cathedral, most probably its successor was constructed directly in front of it - the far grander Norman Minster towering over its ruined predecessor as another symbol of the Conqueror s dominance.

Fragments of Thomas s cathedral remain, including a carved capital which is a copy of one from a Bayeux cathedral. This suggests that stonemasons were brought over to York from Thomas's former home town. Sections of the first Norman Cathedral can be seen in the Minster undercroft.

...and an Abbey

Viking raids had destroyed the Anglo-Saxon monasteries of the north. But within a few years of the Norman Conquest new ones were being founded.

With all of Yorkshire s major landowners as benefactors, St Mary's Abbey became the largest and richest Benedictine monastery in the north.

...and lots of Churches

Most York citizens were far more at home in their local churches and chapels than at the Minster or monasteries. The city was well blessed with churches, with 40 recorded in Norman times.

Churches were places of worship for everyone except the Jews. More than that, as almost the only stone buildings, they were pressed into service as meeting centres, courts, schools and parish gild halls.

Religion played a major part in people s lives. The ever-present risk of falling into sin was reinforced by depictions of the devil in stained glass windows, wall paintings and sculpture. The Doom Stone in the crypt of York Minster portrays various devils forcing souls through the jaws of hell.

An Independent City

The period of York's history between the demise of Eric Bloodaxe in 954 and the arrival of the Normans in 1068 is known as the Anglo-Scandinavian. York was ruled by an English king but was still heavily influenced by viking culture.

It was in a period of relative peace. Eric's conqueror, the English king Eadred, died only a year later in 955 and was eventually succeeded by his nephew Edgar. Edgar was to rule England from 959-975, a time free from foreign attack so he became known as the Peaceable .

According to a contemporary account by this time York was a major city of 30,000 citizens. The city is crammed beyond expression, the account states, and enriched with treasures of merchants, who come from all parts, but above all from the Danish people.

Despite its importance, English kings rarely visited Jorvik. Instead they appointed earls to keep a grip on Northumbria. A story has it that Viking invader King Svein Forkbeard of Denmark was buried in York in 1014.

The Vikings had been good for York, turning it into a thriving, bustling conurbation. By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, York was second only to London in size and prosperity.

The Normans Arrive

Previous southern kings had been content to let the north be. Not so William the Conqueror.

After 1066 York was ‘seething with discontent’, in the words of chronicler Orderic Vitalis. It was a Viking city, with Viking traditions and culture. More than that the whole of the north was in rebellion. So William marched on York in 1068.

William intended to make this large and prosperous city a part of his kingdom.

As he approached, leading citizens gave him hostages and the keys to the city.

But William was determined to stamp his authority on York. He began by building a castle, followed by a second in 1069, leaving 500 knights as a garrison. The city’s continuing importance was thus confirmed - it was the only place in the country with two castles outside London.

York's two Norman castles were designed to control access to the city by river: they were sited on eith side of the Ouse, one at Clifford's Tower and the other at Baille Hill. A chain could be threaded between them to prevent passage on the river.

William was right to be cautious - there was still unrest in the north.

Rebellion and Revenge

To make room for one of his castles, William the Conqueror laid waste to one of the seven shires of York. This only added to the anger and resentment in the city.

In 1069 local forces attacked the two castles without success. But then a more serious challenge emerged: King Swein of Denmark arrived with a large fleet of ships in August of that year. Together with powerful Anglo-Saxon nobles and the people of York, the force took the city, burning the castles to the ground and massacring the Norman occupiers.

Part of the Norman army s defence was to set fire to buildings that might offer shelter to the attackers: the blaze spread and a large part of the city was lost, including the Minster.

There is little evidence that the victors had planned a strategy for what to do when they re-took the city and victory was short lived.

William's Revenge

On hearing the news of his forces defeat at York, William swore a furious oath by the splendour of God to avenge himself on the north. He bribed the Danes to leave the city and advanced to York without opposition.

He repaired the two castles and then, using the city as a base, remorselessly and relentlessly carried out what was became known as the Harrying of the North .

The exact scale of the Harrying is unknown. But it was certainly devastating, with many thousands of deaths, from violence and famine.

Symeon of Durham recorded that 'It was horrible to observe, in houses, streets and roads, human corpses rotting...For no-one survived to cover them with earth, all having perished by the sword and starvation, or left the land of their fathers because of hunger.'

It may be that William later came to regret the scale of the destruction. Chronicler Orderic Vitalis wrote that the king confessed on his deathbed to having treated the native inhabitants of the kingdom with unreasonable severity, cruelly oppressed high and low, unjustly disinherited many, and caused the death of thousands by starvation and war, especially in Yorkshire .

Nevertheless the operation achieved his aim. The rebellion was defeated and the population subdued.

Norman Reconstruction

William stayed in York in Christmas 1069 and it must have been a depressing place. Most great buildings of the Viking age were gone or in ruins. The lively, prosperous capital of the north had been wrecked.

The reconstruction of military buildings began almost immediately. The two rebuilt castles towered over the surviving low houses and the ruined Minster, an unmistakable symbol of the power of the new king.

The city s defences were reinforced in a more unusual way. Near to the larger castle, at Clifford s Tower, a dam was constructed blocking the Foss. The resulting reservoir became known as the King s Fishpool, which provided an impenetrable barrier to the east of the city. This is why there is no wall to that side.

Civilian York took a longer to recover - of the 1,400 or so houses recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086, more than half were deserted and derelict.

However the defences weren t the only interest of the city s Norman rulers, they also embarked on a massive campaign of church building.

Norman Religious Buildings

The religious foundations laid by the Normans are perhaps their greatest legacy.

The last Anglo-Saxon Archbishop of York was Ealdred, who had crowned William the Conqueror at Westminster Abbey.

After Ealdred s death in 1070 a Norman, Thomas of Bayeux, was appointed Archbishop of York and became the single most powerful person in the city.

A New Minster

Thomas set about rebuilding the Minster, a task completed in about 1100. Although we don t know the exact location of the Anglo-Saxon cathedral, most probably its successor was constructed directly in front of it - the far grander Norman Minster towering over its ruined predecessor as another symbol of the Conqueror s dominance.

Fragments of Thomas s cathedral remain, including a carved capital which is a copy of one from a Bayeux cathedral. This suggests that stonemasons were brought over to York from Thomas's former home town. Sections of the first Norman Cathedral can be seen in the Minster undercroft.

...and an Abbey

Viking raids had destroyed the Anglo-Saxon monasteries of the north. But within a few years of the Norman Conquest new ones were being founded.

With all of Yorkshire s major landowners as benefactors, St Mary's Abbey became the largest and richest Benedictine monastery in the north.

...and lots of Churches

Most York citizens were far more at home in their local churches and chapels than at the Minster or monasteries. The city was well blessed with churches, with 40 recorded in Norman times.

Churches were places of worship for everyone except the Jews. More than that, as almost the only stone buildings, they were pressed into service as meeting centres, courts, schools and parish gild halls.

Religion played a major part in people s lives. The ever-present risk of falling into sin was reinforced by depictions of the devil in stained glass windows, wall paintings and sculpture. The Doom Stone in the crypt of York Minster portrays various devils forcing souls through the jaws of hell.

An Independent City

For most of the Norman period York, like the rest of Yorkshire, had been governed by the Sheriff. He was based at York Castle, but had responsibility for the whole county and wasn't accountable to the citizens. This all changed at the beginning of the 13th century.

The Sheriff of Nottingham may have had troubles with outlaws but at least he didn't have to face York's business community. As York’s merchants grew richer, they resented the Sheriff of Yorkshire's dominance. Leading citizens banded together and became an influential voice in the city’s affairs.

It was King John himself who gave them the chance of self-government. Disastrous and expensive military campaigns left him sorely in need of funds, and one way to raise them was to allow a town’s citizens to buy the right to rule themselves. The same pressures forced John in 1215 to sign the Magna Carta, the charter giving some fundamental rights to the nation.

York's own charter came three years earlier, in 1212, when King John allowed York’s citizens, rather than the Sheriff, to collect and pay the annual tax to the Crown,

The Sheriff of Nottingham may have had troubles with outlaws but at least he didn't have to face York's business community. As York’s merchants grew richer, they resented the Sheriff of Yorkshire's dominance. Leading citizens banded together and became an influential voice in the city’s affairs.

It was King John himself who gave them the chance of self-government. Disastrous and expensive military campaigns left him sorely in need of funds, and one way to raise them was to allow a town’s citizens to buy the right to rule themselves. The same pressures forced John in 1215 to sign the Magna Carta, the charter giving some fundamental rights to the nation.

York's own charter came three years earlier, in 1212, when King John allowed York’s citizens, rather than the Sheriff, to collect and pay the annual tax to the Crown,

King John signing the Magna Carta (Goodrich 1844)

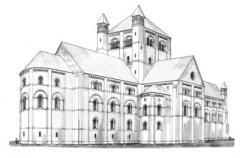

The Norman Minster

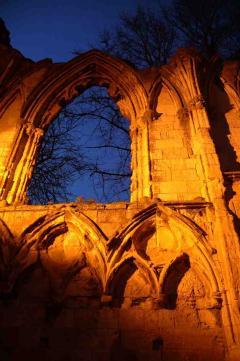

York Abbey church ruins

Illustration of the Norman Castle (from a drawing

by Terry Ball for English Heritage)

by Terry Ball for English Heritage)

Cliffords Tower

the castle tower

the castle tower

Norman soldier reconstruction

to hold their own courts and to appoint a mayor. From then on, until local government reorganisation in 1974, York was a self-governing city under its own mayors.

Hugh Selby, who exported wool and imported wine, became York’s first known mayor in 1217. His family made the role their own: he was appointed a further five times, his son John seven times and his grandson Nicholas four times.

The Sheriff’s remaining power was effectively stripped from him in 1256 by two charters from Henry III which handed over control of the law and justice to the people of York.

Hugh Selby, who exported wool and imported wine, became York’s first known mayor in 1217. His family made the role their own: he was appointed a further five times, his son John seven times and his grandson Nicholas four times.

The Sheriff’s remaining power was effectively stripped from him in 1256 by two charters from Henry III which handed over control of the law and justice to the people of York.

Viking Menu

Viking Timeline

Anglo-Saxon Timeline

NormanTimeline

Pages

Main Coin Menu

Norman Menu

Member NCMD

N. Menu