If you wish to add articles of interest to this site or see a forum, please contact me via my e-mail address. I will 'eventually' reply to all posts. All submitted articles will be author acknowledged unless otherwise requested.

Copyright © 2026 by Nigel G Wilcox

All Rights reserved

E-Mail: TheParagon@gmx.co.uk

Web Title: paragon.myvnc.com

2026

Designed by GOEMO.de

Powered by S-AM3L1A-NGW

NW Education, Training & Development

Looking at Education today, one Perspective...

Parent Site: http://paragon.myvnc.com Paragon Publications UK

My Personal Introduction to Teaching from My Experiences

and the Reason for This Website with Opinions...

Education & Professional Development

Birmingham ICC 2001

1-4

1-4

Pages

Recognising Burn-Out Risks - Case Study 1

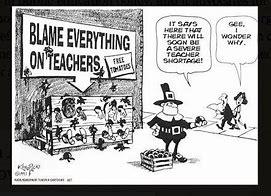

Teachers, Named, Ranked and Blamed?

news | Published in TES magazine on 8 March, 2013 | By: Stephen Exley Section: news

League tables that measure teachers individually are gaining popularity in the US, but their impact can be catastrophic. One such project resulted in a practitioner taking his own life after a poor rating

One autumn morning, Rigoberto Ruelas didn’t turn up for work. His colleagues at Miramonte Elementary School in Los Angeles were worried; in the 14 years he had taught at the school, he had seldom taken a day off.

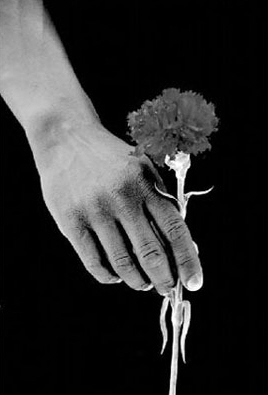

Several days later, a police search-and-rescue team taking part in a training exercise in the Angeles National Forest spotted the 39-year-old’s abandoned vehicle. In a nearby ravine, they found his body lying 100 feet below a bridge. The Los Angeles county coroner later ruled that he had taken his own life.

Despite working in a tough, gang-ridden part of LA, Ruelas adored his job. He would tutor his pupils at weekends, and pushed them to aim high and go to college. Speaking after Rigoberto’s funeral, his brother Jose told journalists: “I want him to be remembered as a person that loved his career, he had a passion for his career. He loved the children and that’s why he taught.”

But according to the Los Angeles Times, he was one of the “least effective” maths teachers in the city. Days before Ruelas’ death in September 2010, the newspaper had entered uncharted territory. In the UK, school league tables have - for better or worse - become accepted as part of our education system. But the Los Angeles Times took things to a new level: it published individual ratings for each of the city’s 6,000 elementary school teachers. It used the value-added measure, comparing individual pupils’ progress in test scores to evaluate what effect their teachers had on their learning.

The project’s impact was seismic. In Ruelas’ case, his family said that he had become deeply depressed by his poor rating. After news of his suicide emerged, thousands of teachers turned up at the newspaper’s office in downtown LA, calling for readers to boycott the paper and demanding that the ratings be removed from its website. The banners on display were emblazoned with angry messages including, “We are more than a test score”, “Demoralising teachers hurts students” and “LA Times, how do you help our kids?”

But in spite of the outrage among the teaching community, value-added teacher ratings have not gone away. The scores can still be viewed on the Los Angeles Times website; Ruelas’ poor rating in maths - and his “average” effectiveness rating for teaching English - can still be viewed, just like those of the thousands of other teachers in the city.

And it’s not just the press that has shown an interest in the data. Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) now calculates its own teacher scores to evaluate the performance of individuals, and similar approaches are in use in many other school districts, such as Chicago and Columbia.

US secretary of education Arne Duncan has also come out in support of the scores, arguing: “The truth can be hard to swallow, but it can only make us better and stronger and smarter.”

Teacher scores have even made their way to the eastern seaboard. In February 2012, The New York Times published performance data for 18,000 elementary school teachers in the city.

And it’s not just the press that has shown an interest in the data. Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) now calculates its own teacher scores to evaluate the performance of individuals, and similar approaches are in use in many other school districts, such as Chicago and Columbia.

US secretary of education Arne Duncan has also come out in support of the scores, arguing: “The truth can be hard to swallow, but it can only make us better and stronger and smarter.”

Teacher scores have even made their way to the eastern seaboard. In February 2012, The New York Times published performance data for 18,000 elementary school teachers in the city.

But is rating individual teachers a genuine means of improving education through accountability? Should an employee’s appraisal be kept private and used purely for professional development, or can putting evaluations in the public domain be a real force for educational improvement?

If LA teachers were unhappy about being publicly named and shamed by the Los Angeles Times, they made sure that the two journalists behind the project - Jason Felch and Jason Song - knew what it felt like. “They were burning me and Jason in effigies,” Felch explains. “There were personal attacks on us. Jason Song got more of it because his name is easier to rhyme than Felch.”

Continued>>>