If you wish to add articles of interest to this site or see a forum, please contact me via my e-mail address. I will 'eventually' reply to all posts. All submitted articles will be author acknowledged unless otherwise requested.

Copyright © 2026 by Nigel G Wilcox

All Rights reserved

E-Mail: ngwilcox100@gmail.com

Web Title: paragon.myvnc.com

2026

Designed by GOEMO.de

Powered by S-AM3L1A-NGW

NW Education, Training & Development

Looking at Education today, one Perspective...

Parent Site: http://paragon.myvnc.com Paragon Publications UK

My Personal Introduction to Teaching from My Experiences

and the Reason for This Website with Opinions...

Education & Professional Development

Birmingham ICC 2001

2-3

2-3

Pages

Left-Wing Education?

The British People Demand Accountability and Action to Rectify this Problem Today!

Is The Teaching Profession so Black & White?

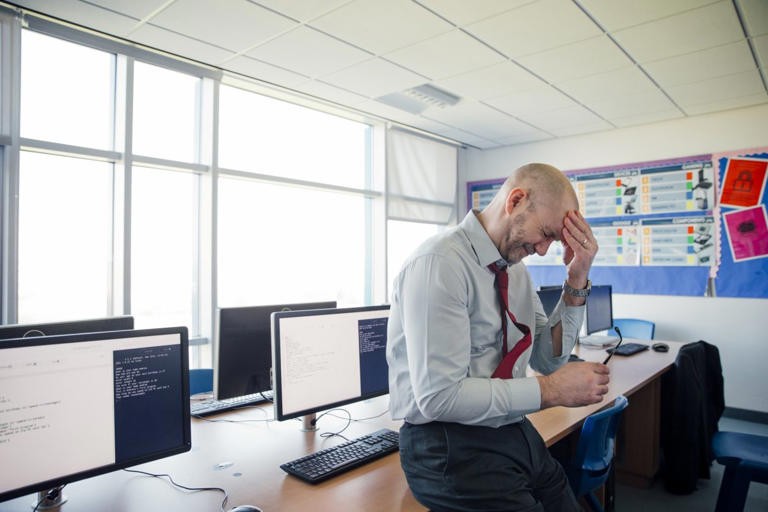

Why Teachers Are Walking Away

“ I thought I was a good teacher and could not understand what was happening ”

Teacher John

|

I’m a teacher – there’s a behaviour crisis in state schools. One change could fix it

"I was punched in the face by a 16-year-old student", says David, 39 Photo: Getty Images/ Graham Oliver)

Continued.....

If the GCSE student who punched me didn’t sit an exam, he would have got a zero. To balance out that single zero, about five other students would each need to achieve one grade above their targets to compensate. Even if a school is doing amazing work overall, just one student failing to complete all their exams can dramatically drag down the school’s measured progress. We would have been hammered by Ofsted.

There was one English GCSE class where it was openly accepted that 10 of these students were going to fail this exam because of SEND issues. It was certain that they were going to receive zero marks because they simply could not understand the material. But because of

Progress 8, they were required to attend seven hours of English lessons every fortnight for two years and then sit the exams.

This is when misbehaviour comes in. For those students, that experience is demoralising. They know they’re likely to fail, they don’t feel successful, and they’re being forced into a system that doesn’t fit their needs. The only way they can express their frustration is by being disruptive. Increasingly, because of a lack of funding, these students are put into mainstream classes with students who are expected to get much higher grades.

Many students simply opt out. They feel like failures, they’re disengaged, and so they stop attending school altogether. But what really escalated after the pandemic, and is still common now, is internal truancy. These students aren’t skipping school entirely. They’re on campus, but they’re not going to the classes they’re supposed to attend. They might show up briefly to be seen and then disappear, spending the day elsewhere in the building instead of in lessons.

I found myself in a ridiculous situation when writing behaviour plans. Given the limited funding and resources, the “safest” approach for some students was essentially to let them wander the school. It sounds absurd, but the idea was to avoid confrontation because if we forced them into classes, it meant they disrupted every lesson they sat in.

It gets even more complicated. We still have a duty to ensure these students are safe, so someone has to monitor them. Ideally, I should have been able to spend time with these kids, building rapport and guiding them back to class. But with a full teaching schedule, I couldn’t devote an hour of my six-hour day to one student. Instead, the job falls to lower-paid staff; support or admin workers, whose role is simply to track the student and make sure they’re physically safe, without providing the support needed to reintegrate them into lessons.

The result? The behaviour continues because we lack the resources to stop it, and the cycle just goes on and on. This has become a significant new behaviour challenge in schools.

We also rarely expel students now. To expel a child costs the school £18,000 a year because they have to pay for the child to go to a special unit, and then, on top of that, they have to pay for the individual taxis to take them to and from this provision. Plus, there are hardly any spaces in these provisions, so a lot of the time, they would have nowhere to go.

But there are some happier stories. One of the students I’m most proud of was a boy who ultimately refused to go to school, which turned out to be remarkably positive. He was in Year 10, from a disrupted home life, and part of a peer group with similar backgrounds. He was clearly heading down a familiar path: escalating misbehaviour and recruitment by local drug dealers to deliver packages. He knew that because that’s what had happened to his older brother and his father.

I was his maths teacher, but I became more of a mentor. We had many conversations, and he understood exactly where his life was heading. At the start of Year 11, he refused to attend school, and he refused to sit his GCSE exams. He locked himself away at home. On the surface, that might seem like failure. But for him, it was an act of self-preservation. By cutting ties with that peer group, he avoided the lure of dealing drugs. I was incredibly proud of him for that, but it shouldn’t be up to children to spot these structural problems and take things into their own hands.