S'sonic

Stealth

Menu

A free template by Lucknowwebs.com for WYSIWYG WebBuilder 8

Powered by Sispro1-S

Nigel G Wilcox

Paragon Of Space Publication

© Copyright Reserved - United Kingdom

Ideal Screen Composition 1024 x 768

SITEMAP

PSEUDO SCIENCE

SCIENCE RESEARCH

ABOUT

Desk

Supersonic

Stealth

Study

Menu

MAIN INDEX

Fastest Air Planes

Space

Transport

Menu

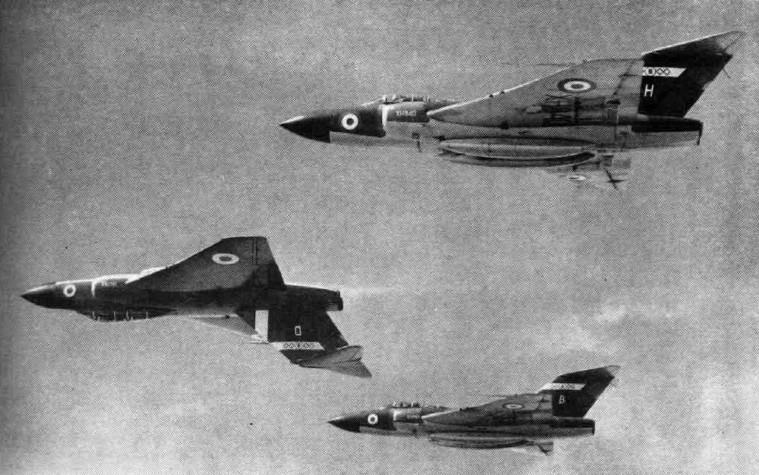

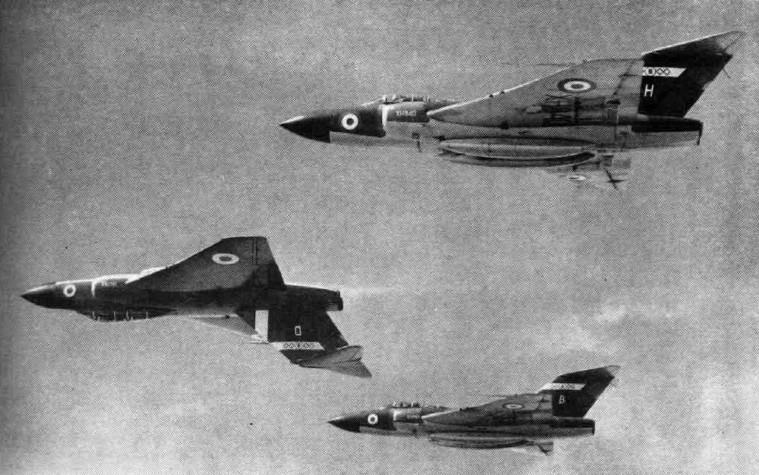

Gloster Javelin

Maiden flight: 26 Nov 1951, Length: 56.75 ft, Wingspan: 52.00 ft, Introduced: 29 Feb 1956, Retired: Apr 1968, Passengers: 2

The Gloster Javelin is a twin-engined T-tailed delta-wing subsonic night and all-weather interceptor aircraft that served with Britain's Royal Air Force from the mid-1950s until the late 1960s. The last aircraft design to bear the Gloster name, it was introduced in 1956 after a lengthy development period and received several upgrades during its lifetime to its engines, radar and weapons, including support for the De Havilland Firestreak air-to-air missile.

Role: All-weather fighter/interceptor

Manufacturer: Gloster Aircraft Company

First flight: 26 November 1951

Introduction: 29 February 1956

Retired: April 1968

Primary user: Royal Air Force

Number built: 436

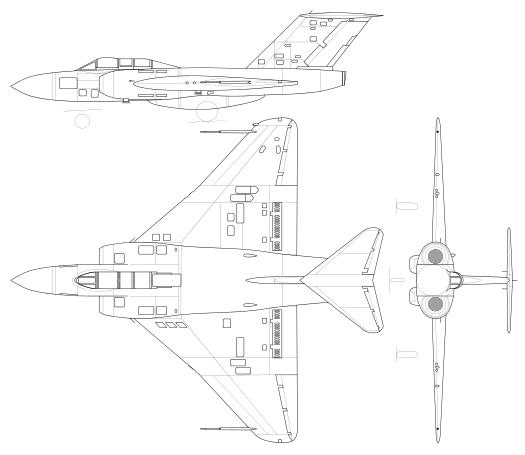

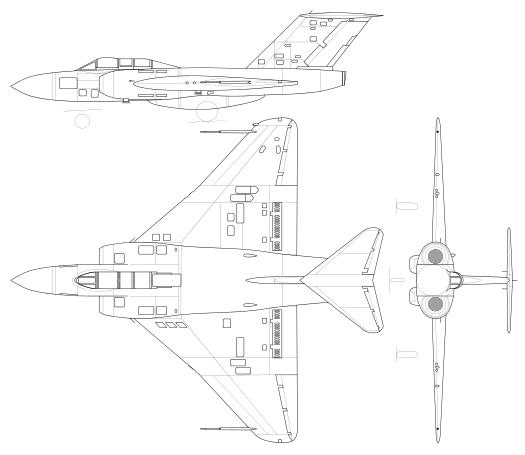

General characteristics

Crew: Two, pilot and radar operator

Length: 56 ft 9 in (17.15 m)

Wingspan: 52 ft (15.85 m)

Height: 16 ft (4.88 m)

Wing area: 927 sq ft (86 m²)

Empty weight: 24,000 lb (10,886 kg)

Loaded weight: 31,580 lb (14,325 kg)

Max. takeoff weight: 43,165 lb (19,580 kg)

Powerplant: 2 × Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire 7R turbojets, 12,300 lbf (54 kN) each.

Performance

Maximum speed: 610 knots at sea level (710 mph 1,140 km/h)

Range: 954 mi (1,530 km)

Service ceiling: 52,800 ft (15,865 m)

Rate of climb: 5,400 ft/min (27.45 m/s)

Wing loading: 34 lb/(sq ft) (166 kg/m²)

Thrust/weight: 0.79

Armament

Guns: 4x 30 mm ADEN cannons

Missiles: Up to four de Havilland Firestreak air-to-air missiles

Avionics

Westinghouse AN/APQ-43 radar

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Britain identified a threat posed by the jet-powered strategic bomber and atomic weaponry and thus placed a great emphasis on developing aerial supremacy through continuing to advance its fighter technology, even following the end of conflict. Gloster Aircraft, having developed and produced the only Allied jet aircraft to be operational during the war, the Gloster Meteor, sought to take advantage of its expertise and responded to a 1947 Air Ministry requirement for a high-performance night fighter under Air Ministry specification F.44/46. The specification called for a two-seat night fighter, that would intercept enemy aircraft at heights of up to at least 40,000 feet. It would also have to reach a maximum speed of no less than 525 kn at this height, be able to perform rapid ascents and attain an altitude of 45,000 feet within ten minutes of engine ignition.

Additional criteria given in the requirement included a minimum flight endurance of two hours, a takeoff distance of 1,500 yards, structural strength to support up to 4g manoeuvres at high speed and for the aircraft to incorporate airborne interception radar, multi-channel VHF radio and various navigational aids. The aircraft would also be required to be economical to produce, at a rate of ten per month for an estimated total of 150 aircraft.

Gloster produced several design proposals in the hope of satisfying the requirement. P.228, drawn up in 1946, was essentially a two-seat Meteor with slightly swept wings. A similar design was also offered to the Royal Navy as the P.231. The later-issued P.234 and P.238 of early 1947 had adopted many of the features that would be distinctive of the Javelin, including the large delta wing and tailplane. The two differed primarily in role; P.234 was a single-seat day fighter with a V-tail, while P.238 was a two-seat night fighter with a mid-mounted delta tailplane.

The RAF requirements were subject to some changes, mainly in regards to radar equipment and armaments; Gloster also initiated some changes as further research was conducted into the aerodynamic properties of the new swept and delta wings, as well as use of the new Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire turbojet engine.

On 13th April 1949, the Ministry of Supply issued instructions to two aircraft manufacturers, Gloster and de Havilland, to each construct four airworthy prototypes of their competing designs to meet the requirement, as well as one airframe each for structural testing. These prototype aircraft were the Gloster GA.5, designed by Richard Walker, and the de Havilland DH.110, the latter of which held the advantage of also being under consideration for the Royal Navy. Development was considerably delayed through political cost-cutting measures, the number of prototypes being trimmed down to an unworkable level of two each before the decision was entirely reversed; this led to the unusual situation where the first production Javelin was actually completed prior to the prototype order being fulfilled.

The first prototype was structurally completed in 1951; one unusual feature of the prototypes was the opaque canopies over the two-man cockpits, it had been believed that visibility was unnecessary and a hindrance to the observer’s role, the only external view available was via small ‘portholes’. Following a month of ground testing, on 26th November 1951, the first prototype conducted its first flight at Moreton Valence airfield. Bill Waterton, Gloster’s Chief Test Pilot, would later describe the Javelin as being “as easy to fly as an Anson”.,although also expressing concern over its inadequate power controls. Disaster nearly struck during one test flight when aerodynamic flutter caused the elevator surfaces to detach in mid-flight; despite the lack of control surfaces, Bill Waterton was able to land the aircraft. He was awarded the George Medal for his actions to retrieve flight data from the burning aircraft.

The second prototype (WD808) received a modified wing in 1953. After initial testing by Waterton, it was passed to another Gloster test pilot, Peter Lawrence for his opinion. On 11th June 1953, the aircraft crashed during testing. Lawrence had ejected from the aircraft, but too late (at about 400 ft (120 m)), and was killed. The Javelin had experienced a “deep stall”; the wing acting like an airbrake had killed forward motion and at the same time stopped airflow over the elevators, leaving them useless. Without elevator control, Lawrence was unable to regain control and the aircraft dropped from the sky. A stall warning device was later developed and implemented for the Javelin.

The third prototype (WT827), and the first to be fitted with operational equipment including radar, first flew on 7th March 1953. The fourth WT827 was passed to the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) for trials and the fifth prototype, WT836, made its first flight in July 1954. On 4th July 1954, a prototype Javelin accidentally achieved supersonic speed during a test flight, the pilot having been distracted by an oxygen supply failure.

The Javelin was reportedly easy to fly even on one engine. The flight controls were fully power-assisted and production aircraft adopted a hydraulic ‘feel’ system for the pilot. The Javelin featured an infinitely variable airbrake; the airbrake proved to be extremely responsive and effective, allowing pilots to conduct rapid descents and heavy braking manoeuvres, enabling equally rapid landings to be performed. The turnaround time between sorties was significantly shorter than with the preceding Gloster Meteor, due to improved ground accessibility and engine ignition sequence. Unlike the Meteor, the Javelin was fitted with ejector seats, at the introduction to service of the type.

In spite of the aircraft’s unorthodox aerodynamic features, the Javelin had a fairly conventional structure and materials, being mainly composed of an aluminium alloy, with some use of steel edging. The fuselage was composed of four sections, the nose (containing the radar radome), the front fuselage, centre fuselage and rear fuselage; the nose and rear fuselage were removable for servicing and easy replacement. The engines were on either side of the centre fuselage section, the internal space in the centre containing the service bay that housed much of the aircraft’s electrical, hydraulic, and avionics subsystems. The engine air intakes were placed on the forward fuselage, running directly from beneath the cockpit rearwards into the delta wing. Electricity was provided by a pair of 6,000 watt, 24-volt generators driven by the auxiliary gearbox; inverters provided AC power for equipment such as some flight instruments and the radar.